Mental health disorder prevalence among children and young people has risen worldwide in the last decade, with evidence to suggest that 75% of mental health disorders have a paediatric aetiology (Department of Health, 2015; Office of National Statistics, 2018). This trend is likely to have been compounded by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the resultant international response (Singh et al, 2020). The pandemic has increased children's risk of isolation, exposure to online bullying, domestic violence and abuse, while necessitating the removal of critical protective factors such as school attendance, social support, and access to therapeutic services (Mansfield et al, 2021; Singh et al, 2020). Therefore, it is likely, as many children internationally have returned to school, that the negative impact upon their mental health will require proactive identification and increased support.

Children and young people can experience a variety of mental health difficulties with a dynamic range of severity, and so mental health presentations which do not meet a service's diagnostic cut off must, nevertheless, be appropriately supported (Colizzi et al, 2020). While specialist mental health services are often reluctant to diagnose mental health disorders in the school-age population, the recognition of children and young people's early-onset symptoms, emerging behaviour changes and lower-level difficulties should be supported and monitored within a stepped system of care (O'Connor et al, 2019). Mental health difficulties in childhood are impactful when unsupported and make the transition into adulthood significantly more difficult (Colizzi et al, 2020). Those with untreated mental health disorders at an early age are more likely to have poorer outcomes as they become adults. Placing an emphasis on early intervention has thus been recognised internationally as an essential goal for reducing mental health-related morbidity (Colizzi et al, 2020).

The increased focus upon the requirement of paediatric mental health support has, however, coincided with a decade of austerity and reduced public spending leading to decreased funding and service provision (Stuckler et al, 2017; UK Youth, 2021). This will likely be worsened in the coming years as the economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic obligates further periods of reduced funding (UK Youth, 2021). Therefore, any initiative to improve the mental health and wellbeing of the school-age population must utilise existing resources available in a cost-effective manner, optimising the role of existing professional groups already well placed to tackle this service requirement (Department of Health, 2015).

Role of the school nurse

School nurses have existed in varying forms in the UK since 1907 (Royal College of Nursing [RCN], 2019) and are thought to be a well-placed mediator between health and education, supporting the public health needs of the paediatric population (Department for Health and Social Care, 2009). School nurses offer universal services to all school-age children in the UK, and more targeted interventions for those in need of extra support (Department of Health, 2012). Historically, school nurses have supported with public health initiatives such as immunisations, obesity, and sexual health concerns, and more recently, mental health conditions (RCN, 2019).

The RCN noted that nurses' compassion and inclusivity empower them to ‘intervene quickly when someone is in distress or crisis’ (Public Health England and RCN, 2015). Within the UK, school nurses are the single biggest workforce trained and skilled to deliver public health for school children (Public Health England and Department of Health, 2014). Safeguarding and child protection is an important aspect of the school nursing role within the UK. Fifty percent of looked-after children have diagnosed mental health disorders, and mental illness is noted to be more common in adults who were neglected or abused as children (House of Commons Education Committee, 2016, Akister et al, 2010). Moreover, with the impact of school closures as part of the COVID-19 response, there are many more children with increased vulnerabilities who will need to be safeguarded (Mansfield et al, 2021). School nurses are often utilised by professionals in a safeguarding role for the early identification of children at risk of abuse, and are seen as ‘trusted adults’ by the children themselves, and so supporting their mental health needs is crucial (Public Health England and Department for Health, 2014). School nurses have a high frequency of contact with vulnerable children and young people compared to other professionals (RCN, 2019). This provides the opportunity to deliver brief interventions to children and young people, rather than the burden falling solely upon specialist mental health services. In short, school nurses could be uniquely placed to support children and young people with mental health difficulties.

Aims

This integrative review aims to identify and critically appraise existing academic literature, in order to ascertain the current role of the school nurse in supporting school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and existing mental health disorders. In doing so, recommendations for future research are made and implications for nursing practice discussed. Owing to the heterogeneity in nature of the role, funding and organisational structures between countries, it was decided to limit this review to the UK. However, findings can be utilised to inform discussion of, and reflection upon, practice in equivalent school nursing services, internationally.

Methods

An integrative review methodology was identified as an appropriate systematic strategy given the paucity of literature on this topic and utility of qualitative data to the research question (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005). Levac et al (2010) noted that accessing multiple study designs is effective, and recognising emerging evidence is crucial. School nursing, as a nursing specialism, has significant literature gaps concerning audit, practice and effectiveness (Yonkaitis, 2017). Therefore, collating data from a variety of sources was important to provide a background to this systematic review and frame the research question. This brief scoping search demonstrated limited robust research papers and resources, and rather significant amounts of grey literature, as well as opinion pieces and local, small-scale studies (Avery, 2017). Moreover, a search of the Cochrane Library returned no results related to this research question. Broadening the methods used and data collated within systematic reviews can lead to a richer understanding of topics, exploring both concepts and theories as well as collated empirical or thematic data (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005). Thus, Whittemore and Knafl's (2005) five-stage process of ‘problem identification’, ‘literature search’ ‘data evaluation’, ‘data analysis’ and ‘presentation’ guided this review. The research question was formulated using the Population, Exposure, Outcome (PEO) tool as a handrail. As a result, ‘UK school-age children (5–19)’ (population), ‘emerging mental health difficulties or existing mental health disorders’ (exposure), and ‘support from UK school nursing services’ (outcome) were identified and informed onward facet analysis (Liberati et al, 2009).

Search strategy

The literature search was conducted on 20th November 2021 using the electronic databases PsycInfo, Embase, OVID Medline and CINAHL. Following a facet analysis, multiple search terms and Boolean operators were utilised, see Table 1. Although literature reviews were excluded, any identified reviews relevant to the topic were cross-checked for further papers of relevance. A search limitation was set according to the publication date (1st of January 2010–20th of November 2021) to ensure that returned literature held relevance to modern-era nursing practice.

Table 1. Search terms and strategy

| PEO Identification | ‘School-age children’ (5–19) | ‘Emerging mental health difficulties or existing mental health diagnoses’ | ‘Support from school nursing services’ | ||

| Facet Analysis | Child/ren OR young adult* OR teenager* OR adolescen* OR young people | AND | Mental health OR mental illness* OR depression OR anxiety OR mental health disorder* OR eating disorder* OR psychiatric OR panic OR phobia* OR psychosis OR self-harm OR self-injury | AND | School nurs* OR specialist community public health nurse OR SCPHN. |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed, academic papers published between January 2010 and November 2021, in the English language, were considered for inclusion based on the following criteria:

- ‘Mental health’, ‘mental illness’ or ‘mental wellbeing’ was considered as the primary outcome or exposure of interest.

- School nurses, (or the school nursing service), were distinctly discussed.

- School-age children (5–19) were the population of primary interest.

- All study designs were permissible for inclusion, excluding reviews.

The following exclusion criteria were also applied:

- Learning disabilities or neuro-developmental disorders (e.g. autistic spectrum disorder) as the exposure of primary interest. Specific learning difficulties or kinetic disorders (e.g. dyslexia, dyspraxia, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) as the exposure of primary interest.

- Physical illness without distinct discussion of mental health.

- Specialised sub-populations as the population of interest (e.g. children in the care of the state, expectant mothers <19 years of age etc.).

- Children or young adults outside of the 5–19 age range as the population of interest. (These are the ages of state-provided education within the UK).

- Non-peer reviewed or non-academic sources (e.g. student theses or journalistic papers).

- Papers relating to school nurses outside of the UK.

Selection strategy

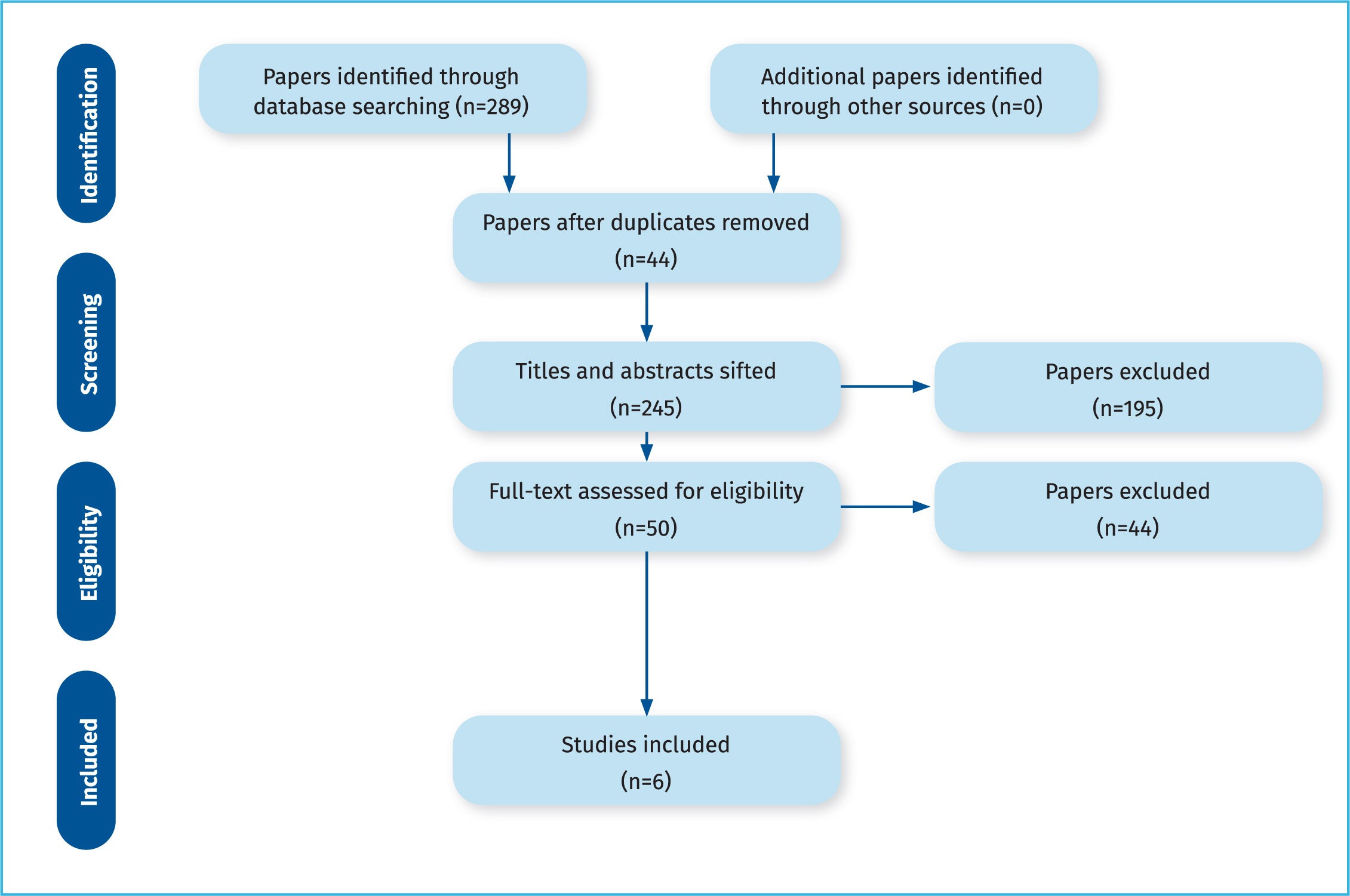

See Figure 1. Articles returned from the above search strategy were de-duplicated. Titles and abstracts were then sifted according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Papers not deemed relevant or applicable were removed. The remaining papers were then accessed in full text and thoroughly assessed for eligibility. Each was then assessed, independently, by two reviewers for relevance before being included for data extraction.

Assessment of methodological quality

An appropriate critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) checklist was selected and utilised for the evaluation of methodological quality for each included study, owing to its evidenced utility for numericised appraisal of several study designs (Munthe-Kaas et al, 2019). Two raters (first and second author) independently assessed and graded each included paper giving it a CASP score. Any disagreements in CASP score triggered a re-evaluation and discussion to reach a consensus.

Data extraction and evaluation

The following data, from the final included papers, were extracted and verified by the first and second authors:

- Location

- Main aim

- Design and method

- Participants

- Key findings

- Limitations

- CASP score.

See Table 2 for the data extracted from each study. Meta-analysis was not possible for the included quantitative studies, owing to the heterogeneity of study designs returned. Nevertheless, quantitative data was extracted and narratively synthetised in combination with a thematic approach to study data comparison across all included studies (Thomas and Harden, 2008). Broad themes, arising from this synthesis of evidence were identified and tabulated. See Table 3.

Table 2. Data extraction of included papers

| Study | Location | Study aims | Design and methods | Participants | Key findings | Limitations | CASP score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doi, Wason, Malden, Jepsen (2018) | UK | To assess the new initiative of refocusing the role of the school nurse, and how more training could be used to support school nurses. | Mixed methods. Interviews, focus groups, and survey data. | N=33 (27 school nurses and 6 managers) across ‘2 sites’ in Scotland. | Mental health pathways were used by school nurses more than other pathways. 68% of children referred were on MH pathways. School nurses can identify those with mental health difficulties but are not adequately trained for interventions. There is limited evidence for school nurse effectiveness. | Aims not clear; focusing on all aspects of school nursing, not just mental health; Small sample size. | 4/10 |

| Haddad, Butler and Tylee (2010) | UK | To identify attitudes of school nurses toward their role in mental health, training requirements, and attitudes toward depression and anxiety. | Quantitative. Cross-sectional study using questionnaires. | N=258 school nurses ‘throughout the United Kingdom’. | Holding a SCPHN qualification had a significant association with improved confidence in working with depressed young people. 46% of school nurses had received no post-qualification training in mental health. 93% of sample agreed or strongly agreed that supporting pupils with psychological or emotional problems was a key part of their work. 79% of sample believed more support from CAMHS would be useful. Positive and non-stigmatising attitudes relating to MH among school nurses also noted. | Unclear sample selection. Low response rate of 37%. Results not clearly written as no access to the content of the surveys; difficult to analyse effectively. | 5/10 |

| Haddad and Tylee (2013) | UK | To test school nurses' knowledge of depression | Quantitative study. Knowledge test and vignettes. | N=146 school nurses from 12 primary health-care trusts. | SCPHNs scored higher levels of specificity in the vignette exercise compared to those without the qualification (although this result was not statistically significant). School nurses were found to score well in identifying depression. School nurses who had more understanding attitudes toward depression were better at identification. | Sample all from London which may not reflect the wider experience of the UK. Vignettes are not real-life scenarios; no chance for extra questions or analysis of the situation, which clinicians would be expected to do. | 5/10 |

| Haddad, Pinfold, Ford, Walsh, Tylee (2018) | UK | To evaluate a training programme intended to improve school nurses' knowledge of depression. | Randomised controlled trial | n=115 school nurses from 13 Primary Care Trusts completed the study. | Training associated with significant improvements in recognition, and knowledge of Depression, (12.7% difference on knowledge measure with large effect size D=0.97). School nurses were keen to refer to other services rather than provide interventions themselves. | Lack of diversity in sample: all from London. Not possible to blind participants to their allocation group. Only 52% completed all outcome measures in the intervention group. | 6/10 |

| Pryjmachuk, Graham, Hadad, Tylee (2011) | UK | To explore school nurses' views on mental health in school-age children and how they can support them. | Qualitative study using focus groups | n=33 school nurses from 4 school nursing teams. | School nurses had a good awareness of mental health issues and also noted associated physical symptoms. Long waiting list for CAMHS. Low confidence reported from school nurses in dealing with the common mental health disorders and self-harm. Lack of training in managing these conditions for school nurses. Heavy caseload in other areas taking priority. | Focus group was self-selecting.Researcher knew some of the participants. | 6/10 |

| Spratt, Phillip, Shucksmith, Kiger, Gair, (2010) | An overview of the work completed by school nurses regarding mental health of children and young people. | Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews. | n=25 school nurse managers across Scotland, from 13 health boards. | Drop-in clinics were valued.School nurse role is unique as confidential and relationships of trust are built. School nurses were perceived as non-judgemental.School nurses had access to health records to offer a medical and holistic approachSchool nurses have few resources and insufficient training to appropriately support school-age children. | Small sample size and all managers-no opinions of school nurses or service users. | 7/10 |

Table 3. Thematic table

| Theme | Sub-theme | Study lead author (year of publication) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haddad (2010) | Spratt (2010) | Pryjmachuk (2011) | Haddad (2013) | Haddad (2018) | Doi (2018) | ||

| Knowledge gaps | Lack of training for staff | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| SCPHN vs non-SCPHN qualified | x | x | x | ||||

| Low confidence levels | x | x | x | ||||

| Lack of resources | Heavy caseloads and limited time | x | x | ||||

| Lack of support from CAMHS | x | x | |||||

| School nurses are in a unique position | Knowledge of physical health issues | x | x | ||||

| Low levels of stigma | x | x | x | ||||

| Ability to identify and assess risk | x | x | x | x | x | ||

Results

Search results

A total of 289 papers were returned from the initial database search. After deduplication, 245 papers were screened by review of titles and abstracts and 195 papers were removed according to adherence to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full text of 50 papers were assessed for eligibility of which 6 papers met the criteria for inclusion in this review (see Figure 1).

Two papers utilised a quantitative study design. Haddad and Tylee (2013) and Haddad et al (2018) both used quantitative data collection methods, with Doi et al (2018), Haddad et al (2010), Pryjmachuk et al (2011) and Spratt et al (2010) using qualitative or mixed methods approaches. Two of the selected studies, Pryjmachuk et al (2011) and Doi et al (2018) used focus groups which was appropriate given the small sample sizes; both had 33 participants, but Doi et al (2018) also combined this data with interviews and quantitative data. Haddad et al (2010) sent questionnaires to school nurses in the post, and Spratt et al (2010) used semi-structured interviews to collect their data. Studies with a quantitative methodology included one randomised controlled trial (RCT) (Haddad et al, 2018), and the other (Haddad and Tylee, 2013), included collecting numericalised data from knowledge tests. This involved ‘knowledge item analysis’, comprised of percentages of correct and incorrect answers given by the school nurses to 60 questions relating to depression, and vignette analyses using numbers to score likelihood of developing depression caseness within 12 case studies. The sample size in the included papers varied from 25 participants in one study (Spratt et al, 2010), to 258 in another (Haddad et al, 2010). The participants included overall were from a range of UK health-care trusts ensuring a good geographical spread of studies.

Two existing reviews, although not included as per exclusion criteria, were identified relating to the topic of school nursing and paediatric mental health (Bartlett, 2015; Ravenna and Cleaver, 2016). Ravenna and Cleaver (2016) included international papers and so their results are not wholly applicable to the UK system. Bartlett (2015) included other aspects of the school nurse role and not just mental health support, which distinguishes the paper from this review.

Quality appraisal

The quality of the papers returned within this systematic review was judged to be of a moderate standard, see Table 2. The CASP tools were used to demonstrate and measure robustness and methodological quality. The main risk of bias with the six papers identified was due to low sample sizes overall or low response rates, and unclear ethical guidelines. Pryjmachuk et al (2011), Spratt et al (2010) and Doi et al (2018) all had small sample sizes. Low response rates with limited author explanation were found in Haddad et al (2010) which reduced data reliability. Pryjmachuk et al (2011) declared that the author knew some of the participants personally, but did not explain any attempts to mitigate biased data collection as a result, which is problematic. In Haddad et al (2010), sample selection and participant inclusion criteria were not presented, and although focus groups were utilised in both Pryjmachuk et al (2011) and Doi et al (2018), this data collection method was only partially justified in these papers, and the limitation of ‘self-selection’ for participants not acknowledged. Two of the papers, Doi et al (2018) and Spratt et al (2010), spoke with managers who had no patient contact. Moreover, none of the papers included the views of any children and young people who use the school nursing service, thus excluding the patient group whose wellbeing is the subject of the investigation. No parents' views were sought in any of the papers returned. This could have been due to ethical considerations, but it is important to note that this systematic review, as a result, only includes the school nurses' and managers' views on the current role of the school nurse in mental health support for school-age pupils. This finding demonstrates a clear knowledge gap within the literature and must be noted as a significant limitation in light of the overall body of data.

Themes

Three broad themes were discovered as a result of the integrative review, see Table 3. Despite limited papers being available on this topic, the emergent themes were identifiable and consistent throughout the six papers included. Each theme and its emergent subthemes are displayed in Table 3.

Theme one: lack of knowledge

Lack of training

All papers identified that a lack of mental health training for school nurses resulted in a problematic knowledge gap which reduced the capability of school nurses to provide mental health support to their pupils (Doi et al, 2018; Haddad et al, 2018; Haddad and Tylee 2013; Pryimachuk et al, 2011; Spratt et al, 2010). Haddad et al (2010) noted that nearly half of school nurses had not received any post-registration training in mental health, which is incongruent to the service requirement. Doi et al (2018), Haddad and Tylee (2013), Haddad et al (2018) and Pryjmachuk et al (2011) all noted that school nurses were well placed and competent to identify mental health difficulties in school-age children. Therefore, the knowledge gap for school nurses could relate, not to the identification of mental illness, but rather to the resultant supportive interventions that are required to support the young people identified. Moreover, Doi et al (2018) and Spratt et al (2010) demonstrated that although mental health support and intervention is seen as a priority in the school-age patient group by service managers, school nurses are not adequately trained in this area of clinical practice. Haddad et al (2018) noted that school nurse mental health training must be realistic and fit for purpose, providing the school nurse with resources to identify, manage, and support mental health disorders in their patient group.

SCPHN vs non-SCPHN qualified school nurses

The specialist community public health nurse (SCPHN) training course leads to a post-registration qualification that registered nurses must complete in order to qualify as a school nurse. The training involves degree level or postgraduate study in multiple areas of practice relevant to school nursing and often includes training relating to the support of school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and diagnosed mental health disorders. Only three studies differentiated participants who held SCPHN qualifications (Haddad et al, 2010; Haddad and Tylee, 2013; Haddad et al, 2018). All three papers investigated school nurses' knowledge of depression as well as competence in identifying depression cases and demonstrated that SCPHN qualified nurses, compared to non-SCPHN nurses, had higher awareness and proficiency in this clinical area (Haddad et al, 2010; Haddad and Tylee, 2013; Haddad et al, 2018).

Low confidence levels

Low confidence among school nurses relating to mental health support and intervention was identified in three of the included papers (Pryjmachuk et al, 2011; Doi et al, 2018; Haddad et al, 2018). Pryjmachuk et al (2011) demonstrated that school nurses reported low confidence in dealing with mental health issues that carried greater physical risk, for example self-harm and eating disorders. Haddad et al (2018) demonstrated that levels of confidence increased after receipt of specific mental health training and so the lack of training and confidence to support school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and diagnosed mental health disorders are likely to be associated. Doi et al (2018) noted that the lack of confidence in providing intervention and support for mental health difficulties or disorder is not fully understood and more research is required. However, lack of training and confidence remain key barriers that ought to be addressed to ensure that school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and diagnosed mental health disorders access the support and management required.

Theme two: lack of resources.

Heavy caseloads and lack of time

Lack of time and resources were identified as barriers in two of the six papers returned (Pryjmachuk et al, 2011; Spratt et al, 2010). Both noted that time pressures were a significant factor in not being able to provide mental health services to school-age children. Caseloads and other priorities such as immunisations, sexual health support and safeguarding were seen to be essential parts of the school nursing service, in addition to mental health support (Pryjmachuk et al, 2011). In addition, lack of available staff members due to many working term-time was also cited as a factor (Pryjmachuk et al, 2011). Spratt et al (2010) noted that lack of training was due to lack of resources, as the time it would take to provide additional training for nurses would mean their workloads would continue to increase. Moreover, infrastructure was highlighted as an important lacking resource, with limited clinical space in schools for school nurses to work appropriately (Doi et al, 2018). This results in nurses being less visible, and thus pupils may be reluctant to access them as a source of support (Spratt et al, 2010).

Lack of support from child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and other services

UK school nurses' lack of access to CAMHS services was demonstrated in two of the six papers (Haddad et al, 2010; Pryjmachuk et al, 2011). Pryjmachuk et al (2011) notes that for one school nursing service in 2003, school nurses had regular supervision from CAMHS practitioners who ran school-nurse lead mental health clinics; a resource no longer in existence. In addition, Haddad et al (2010) noted that CAMHS training would be beneficial to school nurses as well as ongoing clinical supervision and would provide school nurses with support and knowledge to empower improved care. Other health professionals such as GPs were largely excluded in the findings from the selected six papers within the literature. This further demonstrates gaps in the linkage of health services which could be a barrier to maximising outcomes for school-age children with mental health difficulties and disorders (Pryjmachuk et al, 2011).

Theme three: school nurses are in a unique position to support

Knowledge of physical health issues and ability to assess risk

Two out of six papers demonstrated that school nurses were well placed to identify common physical symptoms that often co-morbidly present with mental health difficulties and disorders (Pryjmachuk et al, 2011; Spratt et al, 2010). Pryjmachuk et al (2011) demonstrated that school nurses have a good awareness of physical symptoms associated with mental health issues and can identify concerning presentations, assessing risk accordingly. This ability to identify risk is aided by the school nurses' knowledge of mental health and physical health in combination. Spratt et al (2010) noted that school nurses can offer additional supports by understanding the physical symptoms of mental health presentations during face-to-face consultation. In addition to this, school nurses can distinguish between behavioural issues and mental health difficulties, which is another unique aspect to the role (Pryjmachuk et al, 2011).

Low levels of stigma

Three out of six papers demonstrated that school nurses were understanding and had good awareness of issues surrounding mental ill health (Pryjmachuk et al, 2011; Haddad et al, 2010; Spratt et al, 2010). This allows school nurses to be non-stigmatising in their practice which improves access to their service. Spratt et al (2010) noted that school nurses are viewed, by school-age children, as ‘non-judgmental’ and somewhat separate from teaching staff. Confidential drop-in services empower trusted relationships to be built between the school nurses and pupils, meaning more effective support can be offered. Haddad et al (2010) identified a ‘positive’ attitude from school nurses toward mental health, which was noted as a key strength of the workforce. Pryjmachuk et al (2011) noted increased awareness around mental health and emotional wellbeing among school nurses, which was a factor in maintaining this positive attitude and enabling improved care.

Discussion

The findings from this integrative review have provided clarification to the role of the school nurse in supporting school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties or existing mental health diagnoses.

Knowledge gaps and lack of training for school nurses were identified in all of the studies within this review, resulting in low confidence for school nurses in dealing with mental health difficulties. These findings corroborate existing wider literature relating to a lack of role-specific training for nurses in the UK. Brown (2015) notes there is no statutory requirement for nurses to have mental health training and this is echoed by the RCN (2019) which stated that school nurses could be in a position to provide effective support and early intervention, but require more support and training to enable this. Importantly, this review has evidenced that mental health training can be effective in improving knowledge and confidence among school nurses in this clinical area (Haddad et al, 2018). The Department of Health and Department for Education (2017), supports this capacity for intervention, by noting that school nurses could be as successful as trained therapists in delivering interventions if they had sufficient training. Even in light of extra training being recommended by government guidelines, it is clear from the results of the review that this has not been implemented. More research is required to improve this evidence base, as the intervention study within this review did not capture face-to-face clinical interactions in the interventions tested and so cannot be generalised to real-life school nursing practice (Callard, 2014).

Doi et al (2018) noted that mental health pathways are currently being used more than any other pathway in school nursing. Therefore, the lack of knowledge and training demonstrated within this review is concerning. The most common area of school nursing practice – supporting school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and existing mental health diagnoses – is being conducted without sufficient training. School nurses are expected, by health and education bodies, to be providing this service to children and young people (RCN, 2019), but this review demonstrates there is not sufficient training, confidence or knowledge within school nursing teams to meet this standard. It can be seen in context of the wider literature that nurses do not have enough training to support school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties or existing mental health diagnoses and are too reliant on referring to other services for intervention (RCN, 2016). The lack of NICE guidelines or statutory requirements for mental health training for school nurses is concerning in light of the evidence presented in this review, and demonstrates that school nurses are not receiving the training they require in order to effectively and safely support the mental health needs of school-age children (see National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2009). Evidence-based training packages already exist, such as Youth Mental Health First Aid, Motivational Interviewing, Trauma Informed Care, and Solution Focussed Brief Therapy, but this review has demonstrated that school nurses are not currently accessing these.

This review has identified that the knowledge gaps for school nurses relate to interventions to improve mental health among school age children rather than identification and signposting. Doi et al (2018), Haddad and Tylee (2013), Haddad et al (2018) and Pryjmachuk et al (2011) all note that school nurses are well placed and competent to identify mental health difficulties in school-age children. However, more research is required to understand these competencies in further detail as papers included focused on school nurses' recognition of depression and not identification of behaviours which may be associated with other disorders or emotional and mental distress.

Lack of capacity due to other workload priorities was identified within this review. Pryjmachuk et al (2011) noted that other aspects of the school nursing role, such as safeguarding, are prioritised above mental health support. This is likely to have arisen from nursing and government bodies' insistence that safeguarding and child protection concerns take priority (Department for Health and Social Care, 2009). Public Health England (PHE) (2015) noted that school nurses have an obligation to identify school-age children who are at risk of abuse and neglect, which is a significant part of the school nurse role. However, this siloed view which treats mental health support as distinct from other areas of clinical practice within the school nursing role is problematic. Pupils with whom there are safeguarding concerns have a higher chance of developing mental health conditions (Sugaya et al, 2021). Therefore, safeguarding and mental health practice are inextricably linked and more research is required to understand how school nurses can achieve this holistic support.

Lack of resources also encompasses the scarcity of support from other health professionals, including CAMHS services. The RCN (2014) did note that specialist services are not solely responsible for delivering interventions to support the mental health and wellbeing of school-age children. Therefore, a partnership between school nursing and specialist CAMHS services should be considered, but school nurses should not rely on this to provide interventions for school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and existing mental health diagnoses. Rather, school nurses should instead be trained adequately to provide some interventions themselves (RCN, 2019). Moreover, partnership working between agencies is essential to optimise service provision (Taylor-Robinson et al, 2012). This review evidences a lack of partnership and linkage between school nurses and other professionals working within this clinical area. The resulting autonomous practice of school nurses in managing pupils with mental health difficulties is concerning, given the lack of training identified.

This review evidences that school nurses, as a professional cadre, are well placed to support pupils with mental health difficulties, and are in a unique position compared to other professionals. All of the papers identified this as a key factor and aspect to the school nursing role. School nurses' ability to identify and assess risk, a crucial aspect of supporting pupils with mental health concerns, in combination with a competent knowledge of physical health issues, provides much potential for effective delivery of care in this clinical area. Spratt et al (2010) noted that school nurses have access to health records which may also support in identifying risk factors for mental illness, or existing symptoms identified by other medical professionals. This enables school nurses to offer a ‘holistic’ approach to support both the physical and mental wellbeing of the school-age population. This is supported by NICE (2009) which noted the important link between physical health and emotional wellbeing, and the focus on parity between the two, by both the Department for Health and Public Health England (2014).

School nurses were also found in this review to be non-judgmental and non-stigmatising compared to other professions (Haddad et al, 2010). This enabled them to retain therapeutic relationships of trust with their pupils. Further research involving school-age pupils themselves is required to corroborate these findings, as all studies exclusively sought the perspective of non-service users. Both Public Health England and RCN noted that nurses' ‘compassion and inclusivity’ enable their ability to intervene appropriately (Public Health England and RCN, 2015). This speaks to the potential of school nurses to provide effective care in this clinical area. Indeed, the Department of Health (2014) noted that school nurses are the single biggest workforce trained to deliver public health interventions to school-age children, and thus their capability cannot be underestimated. The review demonstrates that with additional training and improved resources, school nurses could be well placed to support school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and existing mental health diagnoses.

Limitations

This integrative review has a number of limitations, all of which will be acknowledged and discussed. Only six papers were included, demonstrating scarcity of the literature, thus the findings should be interpreted with caution as they may not be generalisable. Sample sizes were small in half of the studies included (see Spratt et al, 2010, Pryjmachuk et al, 2011, Doi et al, 2018) and many of the samples were not representative of the school-nursing population (Pryjmachuk et al, 2011). Furthermore, while study quality was of moderate standard overall, this subject area is an emerging field of research so many studies were preliminary in nature. This should urge caution with regards to the interpretation of findings. Many of the studies were self-reported by school nurses, and while the nurses may report an understanding of mental health difficulties, this was only tested against an objective standard in one paper (Haddad and Tylee, 2013). Indeed, with nearly half of school nurses receiving no extra training, their reported high levels of awareness of mental health issues may be inaccurate (Pryjmachuk et al, 2011). Moreover, some of the studies were not robust due to low response rates (see Haddad et al, 2010). A further limitation is that only three studies distinguished between qualified SCPHNs and unqualified school nurses (Haddad et al, 2010, Haddad and Tylee 2013, and Haddad et al, 2018). The SCPHN course contains modules on mental health and offers, at a higher academic level, the rationale underpinning school nurse interventions. Therefore, this differentiation is crucial.

Moreover, the selected studies excluded views of service users. School nursing services are expected to provide a universal service to every pupil between 5–19 in the UK, approximately 8.82 million children (Department for Education, 2019). Therefore, it is important to seek children's views regarding their own care to ensure services are targeted effectively (Care Quality Commission, 2017). In addition, views of other professionals, such as specialist mental health services were not sought, and thus the finding that CAMHS services are not available needs to be further investigated.

The final limitation is a lack of data to demonstrate how school nurses are currently practising. Many of the selected studies did not quantitatively capture the prioritisation of school nurses' work, except for Doi et al (2018). Auditing numbers of CAMHS referrals, number of pupils in drop-in clinics, and any therapeutic interventions by school nurses were not noted in the remaining papers, and would be valuable.

Relevance to clinical practice

The findings from this integrative review have many implications for school nursing practice and research. Firstly, school nurses need more training and competency development in order to support school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and existing mental health diagnoses. It was clearly noted in Haddad et al (2018) that when this training is put in place, it can produce positive results and this needs to be prioritised. Not only on a local level within individual school nurse teams, based on their own demographics and commissioned services, but national guidance should be filtered down to local teams. Training ‘toolkits’ with a variety of resources could be considered for school nurses, as the guidance overall is clear that school nurses should play a pivotal role in supporting the school-age population with emerging mental health difficulties and existing mental health diagnoses. For example, the RCN (2019) provides guidelines for managing self-harming and have developed a school nursing toolkit which includes information about supporting pupils with mental health difficulties. However, it is not clear from the literature identified within this review whether school nurses have access to these resources and if it is of sufficient robustness to guide a service plan. Moreover, it is recommended that both national and local quantitative research is conducted to assess school nurses' current level of knowledge and competency. This is necessary to build on the findings from this review and ascertain if school nurses are currently practising safely and within their competency. Focusing training for school nurses on interventions including Youth Mental Health First Aid could be beneficial, as this already comes with a robust evidence base (Morgan et al, 2018). Motivational Interviewing (Cryer and Atkinson, 2015) and Solution Focussed Brief Therapy (Franklin et al, 2017) could also be explored and researched as potential future interventions delivered by school nurses.

Another recommendation for practice is that safeguarding and mental health should be viewed as linked and co-dependent areas of practice. Existing literature, in combination with the findings of this review, evidence a need for school nurses to support pupils where there are safeguarding concerns and a higher chance of developing mental health conditions (Public Health England, 2016). Indeed, the lack of discussion of this issue within the included literature is concerning for practice. Pryjmachuk et al (2011) noted that safeguarding work takes priority over other aspects of the school nurse role, including mental health. Given that those children who suffer abuse are more likely to experience mental health difficulties than those who do not, mental health support should be embedded within safeguarding practice for school nurse teams (Department of Health and Department for Education, 2017). Thus, understanding why this is a knowledge gap would be important for improving practice in light of the above evidence, and improving outcomes for the most vulnerable school-age children. Training courses such as Youth Mental Health First Aid (Morgan et al, 2018), or training relating to trauma informed care (Purkey et al, 2018) could complement this area of development for school nurses, with the importance of recognising adverse childhood experiences.

This review has identified that school nursing services should collaboratively work with other Tier 1 and Tier 2 providers of mental health services. For example, CAMHS and GP services were frequently referenced in the legislation and guidance (see Department for Education, 2018), but the literature review showed lack of coherence between these services, which was resulting in limited inter-agency working and negative feelings toward CAMHS among school nurses (see Pryjmachuk et al, 2011). Therefore, assessing the views of GP and CAMHS services in relation to the school nurse role is an important area for future research. Local audits and research could be utilised, as national guidance already obliges agencies to work together (Taylor-Robinson et al, 2012). Because of the changing nature of Clinical Commissioning Groups, local rather than nationally focused research is required as well (Allan et al, 2017). This could also include assessing forms of supervision which could be offered by local CAMHS services for school nurses, including using both clinical and reflective models (Clouder and Sellars, 2004). This is a recommendation for exploration and further research.

The final recommendation arising from this review is to provide evidence for the claims in government legislation and guidance that school nurses are the best placed service to support school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and existing mental health diagnoses (Department of Health and Public Health England, 2014). This integrative review has demonstrated lacking evidence concerning this assertion, and school nurses' scope of practice needs to be ascertained at both local and national levels. School nursing, as a nursing specialism, has significant literature gaps concerning audit, practice and effectiveness (Yonkaitis, 2017). Therefore, looking at international literature in relation to similar school nursing provisions would be useful. Utilising service users and other professionals in future research is recommended, as it would assist in establishing whether school nurses are the best-placed professionals to support school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and existing mental health diagnoses.

Conclusions

This review has investigated the role of the school nurse supporting school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and existing mental health diagnoses within the UK. School nurses lack training to effectively support school-age children with emerging mental health difficulties and existing mental health diagnoses, and limited resources within school nursing and mental health services result in barriers to providing effective intervention. Therefore, while school nurses were found to be uniquely placed to support school-age children, there are significant barriers to be overcome. The lack of training and knowledge within this clinical subject area is an urgent cause for concern and the findings from this review should be utilised for future research and practice improvement.

KEY POINTS

- This integrative review has found that school nurses could be well-placed to support children and young people with emerging or existing mental health concerns.

- However, barriers include a lack of resources within school nursing teams including time and access to training opportunities to develop their knowledge around supporting children with mental health concerns, and low confidence levels reported by school nurses.

- Links between mental health concerns in children and safeguarding issues are clear as part of the school-nurse role, and the role of partnership working to improve outcomes for children was discussed in this review.

- More research is needed, including seeking the views of other health and educational professionals, and children and young people themselves.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- Why might school-nurses be viewed as ‘trusted professionals’? What is unique about the role of the school nurse?

- What mental health training do nurses working with children have compared to those specializing in school nursing? Do you think this is adequate?

- How can existing resources and the current workforce be utilized to provide support that is needed to children and young people with regards to their mental health and emotional wellbeing?

- Are barriers to partnership working common within community and public health nursing? Why might this be?

- Why is it difficult to ascertain the views of children and young people in research?