Prematurity can be defined as babies being born alive before 37 weeks of pregnancy (World Health Organization [WHO], 2018). It equates to 7% of all births in the UK (Office for National Statistics, 2017) and is categorised based on birth gestational age as extremely preterm (<28 weeks), very preterm (28–32 weeks) and moderate-to-late preterm (32–37 weeks) (WHO, 2018). Preterm birth can be provider-initiated (caesarean or induced labour) or spontaneous (Vogel et al, 2018). There continues to be a rise in the number of extremely preterm births recorded (Bliss, 2018). Furthermore, there has also been an increase in rates of multiple births which are seven times more likely to need admission due to prematurity (Bliss, 2018; Twins and Multiple Births Association, 2019).

A variety of risk factors can cause prematurity (Vogel et al, 2018). Liem et al (2012) found people from black and minority ethnic groups, adolescents and women of advanced maternal age have an increased risk (Kozuki et al, 2013; Waldenström et al, 2014). Prematurity has been linked with socio-economic disadvantage and life events (Vos et al, 2014) such as domestic violence, which increases the chances of low birth weight (Hill et al, 2016); maternal smoking and drug use are also risk factors (Foray, 2016). Maternal mental health, pregnancy-related depression, anxiety and stress increase the likelihood of preterm birth (Staneva et al, 2015). Environmentally, air pollution correlates with increased risk (Sapkota et al, 2012; Lamichhane et al, 2015). Two thirds of preterm births arise with unknown causes (Vogel et al, 2018).

Neonatal technological and therapeutic advances have resulted in changes to clinical outcomes of extreme prematurity (Glass et al, 2015). Survival rates continue to rise (Manktelow et al, 2013), resulting in longer lengths of hospitalisation for extremely premature infants (Seaton et al, 2018). Furthermore, many of these surviving infants have life-long disabilities and long-standing health and developmental issues (Whittingham et al, 2014), with morbidity in extremely premature infants also increasing (Delgado Galeano and Villamizar Carvajal, 2016). This is due to immaturity of organ systems and the invasive medical interventions often required for survival (McCormick et al, 2011).

The transition from hospital to community care has been reported as challenging for this group of parents (Boykova, 2016). Life After Neonatal Care (The Smallest Things, 2017) reported survey responses from over 1600 mothers; of these, only 26% felt health visitors understood their or their baby's needs. Almost half of the premature infants in this report had been readmitted to hospital following discharge and more than half of parents said they worried about long-term health outcomes (The Smallest Things, 2017).

Tidy and Knott (2021) found infants born with extremely low birth weight have more hospital readmissions in their early childhood. Causes include lactation issues and infections (Premji et al, 2012). Late preterm infants can experience poor growth due to the inability to breastfeed effectively with reduced gastrointestinal motility and delay of gastric emptying, immature feeding behaviours and gastro-oesophageal reflux (Premji et al, 2012). Although many premature children grow up to be healthy, it has been shown that the late preterm population is also at an increased risk of developing cognitive, behavioural and emotional issues (Kugelman and Colin, 2013). These potentially complex and long-term health needs have led to demand for health professionals in the community to provide enhanced support to this growing population of preterm infants and their parents (McCormick et al, 2011).

Community healthcare can be difficult to define, as this diverse sector offers a range of services across different settings that are less visible than those in hospital (Charles, 2019). In England, child health services broadly include health visiting and school nursing, offering health promotion and a universal public health service (Charles, 2019). It also encompasses specialist services such as children's nursing, physiotherapy, speech and language therapy (SALT) and nutrition (Charles, 2019), offering targeted input for children with additional health needs.

The importance of co-ordinated and joined-up care between hospital and community services for this vulnerable patient group has been recognised in national and global policies in th UK. The Toolkit for High Quality Neonatal Services (Department of Health and Social Care [DHSC], 2009), the first framework in the UK outlining high-quality neonatal healthcare, aimed to improve management of long-term care, recommending joined-up commissioning and consideration of community care as part of the neonatal care pathway.

Born Too Soon (WHO, 2012) was structured around the importance of providing care as a continuum, emphasising delivery of healthcare packages across time and through different service levels. The National Maternal and Neonatal Safety Collaborative emphasised the importance of community hubs (National Maternity Review, 2017), promoting effective partnership between specialist and community services. In the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2019), maternity systems are combining NHS and local authorities, advocating that families receive seamless care when transitioning between services such as neonatal units and health visiting. It outlines reconfiguration of community services around primary care networks, with all areas expanding their multidisciplinary teams to strengthen services, especially for vulnerable patient groups.

Despite these priorities in local and global policy, it is not clear whether this strengthened and co-ordinated care is being offered to families after discharge of their premature infant home into the community.

Review aims

This systematic literature review aimed to provide an understanding of parents' experiences of community care after their premature infant is discharged home. By synthesising available research, gaps in any service provision were identified and recommendations to enhance community care made.

It is hoped this review will contribute to improving community health professionals' awareness of the needs of premature infants and their parents, enriching parents' experiences and facilitating improved long-term care of premature infants. Specific objectives were to:

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature review provides a summary of research by identifying, selecting and critically appraising a collection of studies to answer a specific question (Bettany et al, 2016; Dewey and Drahota, 2016). A systematic and structured approach to the search, appraisal, analysis and synthesis of research is vital (Aveyard et al, 2016). Employing a systematic review methodology aims to facilitate rigor and objectivity, avoiding bias (Arthur et al, 2012; Cooke et al, 2012). It is imperative to have a well-developed research question as this provides the foundation for the review protocol (Bettany-Saltikov, 2012). The Population, Exposure, Outcome (PEO) framework is ideal for qualitative research (Butler et al, 2016) and was used in this search strategy as it was deemed most appropriate for the research question.

Table 1 outlines the search terms and synonyms used. The key words and subject headings were searched individually to determine the exact number of hits for each search term (Hartzell and Fineout-Overholt, 2019). The searches of synonyms were combined with the Boolean operator ‘OR.’ The subject headings and key words for each concept were then combined with the Boolean operator ‘AND’. Following identification of the key search terms, the truncation (*) was used to retrieve additional letters beyond the word that is identified (Hartzell and Fineout-Overholt, 2019). Robust and replicable systematic searches of three electronic databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE and Embase) were conducted.

| Concept | Population | Exposure | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key words | Parent* |

Pre-term bab* |

“community care” |

Experience* |

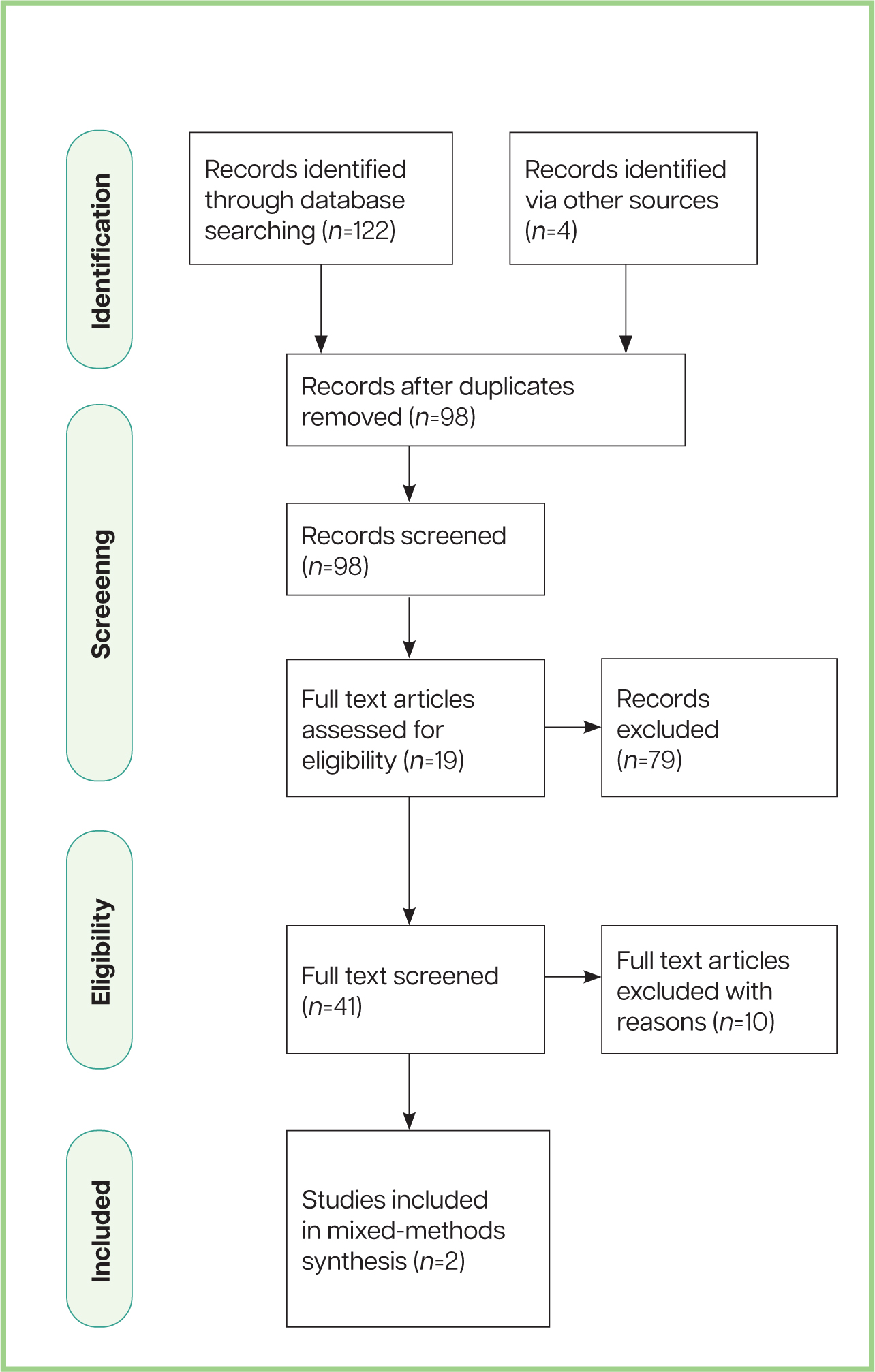

Following a predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2) and completion of supplementary searching (Figure 1) (Moher et al, 2009), nine chosen papers were identified (Box 1). The total number of relevant papers from the electronic search was eight, including six qualitative and two mixed-methods papers and one additional paper was selected by hand searching.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Parents of premature infants born extremely pre-term, very pre-term or late pre-term, as per the WHO (2018) prematurity definition | Any research including parents of term infants who have been admitted to the neonatal unit |

| Any primary research investigating parents of premature infants' experiences of community care following discharge home | Any research of parental experiences of neonatal care, while their infant is admitted to the neonatal unit | |

| Exposure | Support provided to parents from community-based healthcare professionals | Any studies undertaken researching specifically neonatal outreach teams or support from any other professionals working closely with the neonatal unit, and are based in the hospital |

| Outcome | Parents' experiences in the form of qualitative data or mixed methods | Papers with quantitative data only |

Summary of included studies

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2018) Qualitative Checklist and Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was used to review the trustworthiness, reliability and validity of the studies selected and synthesise the papers.

Data analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2021) was undertaken to allow the emergence of seven themes from the data set. Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) is a theoretically flexible method of identifying themes or patterns in qualitative data to answer a research question (Maguire and Delahunt, 2017). It is a powerful method that is well suited to answering a research question aiming to understand a collective of people's experiences, perceptions and views across a data set (Braun and Clarke, 2012).

Braun and Clarke's (2006) six-phase framework for thematic analysis was used as a model for the analysis, where data is organised in a systematic and meaningful way (Maguire and Delahunt, 2017). Open coding was used to generate initial codes from the data, developing these throughout the coding process (Maguire and Delahunt, 2017). Completed by hand, extracts of data were highlighted in a Microsoft Word document. This led to the development of preliminary themes. Vaismoradi et al (2016) describe qualitative analysis as cyclic, requiring researchers to repeatedly return to their data and coding throughout the analysis.

Themes

The narrative of parents' experiences of community care after their premature infant is discharged home is included in the following interwoven themes: gap in the knowledge base, challenges with communication, lack of continuity of care, feelings of abandonment, lack of support for fathers, varied experiences with public health nurses and health visitors, and the importance of competent multidisciplinary team support.

The themes were deemed closely linked; therefore, three superordinate themes were formed merging these (Figure 2). This article will discuss the first superordinate theme.

There is a lack of effective service provision for preterm infants and their parents in the community

Lack of continuity of care

Disjointed co-ordination and co-operation among the multidisciplinary team and an absence of an accountable community professional, contributed to the lack of continuity of care and support (Premji et al, 2017; Ericson and Palmér, 2019; Seppänen et al, 2020). Additional research has identified that there is a gap in the support available to parents when their premature infant is discharged home (Murdoch and Franck, 2012; Boykova, 2016; Franck et al, 2017; Alderdice et al, 2018; Davis-Strauss et al, 2020).

With current policies (National Maternity Review, 2017; NHS England, 2019) recommending that these families receive seamless care in the transition from acute to primary services and thereafter, highlighting the needs of this vulnerable patient group, it is concerning that this is not occurring in practice.

Parents reported a lack of emotional support in the community (Petty et al, 2018; Breivold et al, 2019). There is a lack of consistent care delivery, where parents did not always receive a good response from their public health nurse in relation to their emotional wellbeing and pointed out how important this is to facilitate discussion about their mental health (Breivold et al, 2019). This is troubling as parents report the significant emotional burden of having a baby admitted to the neonatal unit, often resulting in anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep deprivation and feelings of helplessness (Busse et al, 2013).

Boykova (2016) discussed the long-lasting impact of this trauma and experience. Parents of preterm infants reported symptoms correlating with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with heightened fears of rehospitalisation and ongoing worries about their infant's health (Brandon et al, 2011; Lasiuk et al, 2013), and a direct impact on how they use health services (Boykova, 2016).

Parents report that these intense emotional reactions can continue years after discharge. One mother reported that she was diagnosed with PTSD a year after her baby was discharged home (Petty et al, 2018). The emotional journey of parents in the years following discharge is a new and developing area of interest in research (Petty et al, 2018).

The lack of continuity of care is leading parents to feel abandoned in the community, which has been reported to have an effect on mothers' ability to breastfeed. Ericson and Palmér (2019) suggest that mothers feel they are thrown into a lottery, depending on their health professional, concerning community breastfeeding support. Many mothers of preterm infants want to breastfeed, but this is not always possible (Grundvig Nylund et al, 2020) due to challenges including breast milk expression, milk supply issues and immature infant feeding behaviours (Kair et al, 2015; Dosani et al, 2017). The physiological benefits of breastfeeding for premature infants include neurodevelopment (Belfort et al, 2016), specifically promoting cognitive function and early brain development, which can have significant public health implications (Niu et al, 2020).

‘There is a requirement for further consideration of fathers' mental and emotional health, where all community professionals adopt a family-centred approach to providing support, incorporating the fathers' needs in all stages of care’

Feeding was identified as a crucial area for support; one mother described breastfeeding as her ‘salvation’ (Grundvig Nylund et al, 2020: 4). However, Breivold et al (2019) found parents feel there is inadequate feeding support, despite this being key to enabling mothers to feel a sense of achievement, which can also affect their coping and wellbeing following discharge. Premji et al (2017) found that mothers wanted more support and easier access to health professionals for feeding. Some mothers reported feeling abandoned during this period (Premji et al, 2017).

Lack of support for fathers

A crucial aspect of this review concerns a lack of support for fathers, reflecting parents' feelings of abandonment in the community. Premji et al (2019) found that public health nurses commonly still deliver a mother- and infant-centred care approach, often leaving fathers excluded. This is supported by Benzies and Magill-Evans (2015), who found that first-time fathers of late preterm infants felt on the periphery of care.

A report published by the Fatherhood Institute (Howl, 2019) promoted family-inclusive health services, arguing for the importance of including and engaging fathers in the perinatal period, specifically in supporting breastfeeding. It is interesting that a study by Ericson and Palmér (2019) comprised only mothers, when it is clear fathers have an influential impact on supporting mothers in successfully sustaining breastfeeding, despite not being directly involved in the act itself (Howl, 2019). Furthermore, although parents are considered a partnership, their needs differ, with fathers having different coping mechanisms to mothers (Aydon et al, 2018), demonstrating that a mother–infant approach may not address the needs of fathers.

In a recent study (Fatherhood Institute, 2018), half of respondents reported that NHS professionals who visited following the birth ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ spoke about fathers or their roles. Although research has identified that a father's mental health closely correlates with that of the mother, it was concerning that only 18% of fathers had been questioned about this (Fatherhood Institute, 2018).

Five studies in this review included fathers; however, research by Grundvig Nylund et al (2020) included only three fathers out of a sample of 12 parents; Håkstad et al (2016) included four fathers out of seven parents, representing the mothers of all the children, but fathers of only four. Petty et al (2018) included two fathers out of seven parents and Seppänen et al (2020) reported that only 15% of fathers responded, in comparison to 83% of mothers.

Premji et al (2019) stated that the mothers eligible from their initial study (Premji et al, 2017) indicated fathers' willingness to participate, with approximately two thirds of mothers declining paternal participation. The challenges in recruiting fathers were discussed by Premji et al (2019), who found that, of the 53 fathers identified as being willing to participate, only 48 gave permission to be contacted. Following purposive sampling, five agreed to be interviewed, with 10 not responding. This recruitment strategy has been discussed as a limitation by Premji et al (2019), identifying that maternal gatekeeping can have a negative impact and influence fathers' involvement (Fagan and Barnett, 2003), recommending that fathers should be directly contacted for future research.

Arguably, this is also relevant in practice in that fathers should be directly addressed to encourage discussion of their individual needs. Fathers need to be treated more equitably in the ethos of community care (Premji et al, 2019). More research is required exploring paternal experiences following discharge home of preterm infants to facilitate this.

Limitations

This review was conducted as part of a Master's level accreditation and the selection of papers was completed by one person, as were all other stages of the research process, a recognisable limitation. The small number of papers included in this review is also a limitation. This topic is a growing area of interest, and although only nine papers met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, these enabled conclusions to be drawn. As part of the inclusion criteria grey literature was not included, which may have introduced publication bias. As research into this area grows, a more robust exploration of findings could be achieved, increasing validity and reliability of the study (Patuasso, 2013).

Recommendations

Practice

Research

Conclusion

This article has summarised a literature review that aimed to explore parents' experiences of community care after their premature infant is discharged home. From the findings of this review, parents report a lack of support and effective service provision in the community, despite many of these infants having complex disabilities and remaining vulnerable to ongoing health and developmental issues (Whittingham et al, 2014). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2017) guidance indicates that professionals should provide parents of premature infants with emotional support, recognising the significant impact having a premature infant can have. This ongoing support is key for both parents, including fathers and partners. Preterm birth continues to be a global public health priority (Vogel et al, 2018).

This review found that parents feel there is a lack of continuity of care in the community. The fragility of premature infants (Garfield et al, 2014), their parents' caregiving challenges and lack of consistency in primary healthcare (Bowles et al, 2016) can result in a complex care requirement at home (Granero-Molina et al, 2019); however, parents feel there is a lack of effective service provision in place to support them adequately. Parents identified a lack of emotional support and a lack of feeding support in the community, despite the emotional burden of having a premature infant being well recognised in research (Brandon et al, 2011; Busse et al, 2013; Boykova, 2016). Specifically, it has been highlighted that there is a deficiency of community support for fathers, leaving fathers feeling excluded and their individual needs left unaddressed (Premji et al, 2019).

More infants are being born extremely prematurely (Bliss, 2018), and survival in the neonatal unit is not enough. If these infants and parents do not receive appropriate support in the community following discharge, infant neurodevelopment and family psychosocial outcomes are at risk in the long term (Seppänen et al, 2020). Niebler (2010: 2) argues it is time to listen as parents of premature infants are making themselves heard. Renewed emphasis on developing public healthcare models to strengthen community-based care is required, with the provision of enhanced support to premature infants and their parents alongside co-ordinated family-centred follow-up programmes in the community (Seppänen et al, 2020).

Part two of this article in a forthcoming issue of JFCH will discuss further themes derived from this literature review.