Poverty in the UK is having a serious impact on children's lives. More than one in five people in the UK (22%) were in poverty in 2021/22 – 14.4 million people. Of these, 8.1 million were working-age adults, 4.2 million were children and 2.1 million were pensioners (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2024). This means around two in every 10 adults are in poverty in the UK, with about three in every 10 children being in poverty. The number and proportion of children in poverty rose between 2020/21 and 2021/22 and reflects their position as having the highest poverty rates in the overall population (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2024). There is an urgent need for school nurses to support families. At the same time, school nursing activity appears at an all-time low with the demands of safeguarding consuming much of their time (Sammut et al, 2022).

Children living in poverty are more likely to experience stress, anxiety, and depression due to factors such as food insecurity, inadequate housing and limited access to extracurricular activities.

These stressors can significantly affect their mental wellbeing and development. Those in the poorest 20% of households in the UK are four times more likely to develop mental health issues compared to the wealthiest 20% (Commission for Equality in Mental Health, 2021). Adverse childhood experiences, which negatively affect mental health, are three times more common when living in poverty (Institute of Health Equity, 2020). A King's Fund report found mental health service demands to be higher among more deprived communities (The King's Fund, 2022).

Socially deprived young people have poorer sexual health outcomes, with disproportionately high rates of STIs (House of Commons, 2024). Teenage pregnancy is also associated with socioeconomic deprivation (McLeod, 2001; Office for National Statistics, 2019; Aluga and Okolie, 2021).

The author's own action research conducted as a school nurse identified correlations between young people's sexual health and mental health. It became evident from talking to young people about their sexual behaviour that risk-taking was due to emotional and psychological issues (Day, 2024).

A systematised review has been conducted to identify progress in two key areas of practice in the school nursing profession: sexual and mental health, between 2018 and 2023. Systematised reviews ‘attempt to include one or more elements of the systematic review process while stopping short of claiming that the resultant output is a systematic review’ (Grant and Booth, 2009: 102). Systematised reviews are typically conducted by postgraduate students ‘in recognition that they are not able to draw upon the resources required for a full systematic review (such as two reviewers)’ (Grant and Booth, 2009: 102-3).

The systematised review is based on the research question: To what extent has there been enhancement of the service provision in sexual and mental health in the school nursing profession between 2018 and 2023? The research question focuses thoughts and efforts, assisting in developing a framework to guide the researcher (Cormack and Benton, 2000: 79).

Methods

The systematised review used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al, 2021). Data extraction was undertaken by the author. The study used the Mixed Methods Appraisal tool (MMAT) (Hong et al, 2018) for qualitative research, which includes questions that consider potential bias by the researcher, and how they addressed it.

Coding and thematic analysis were undertaken according to Braun and Clarke's guide to thematic analysis (2006). The search used the keywords and Boolean operators in Table 1.

| ‘School nurses’ ‘sex education’ OR ‘sex AND ed’ OR ‘sexual health’ OR making OR problem-solving | AND | OR ‘school nurs*’ ‘sex education’ OR ‘sex AND ed’ OR ‘sexual health’ OR ‘sex education’ OR ‘sex AND ed’ OR ‘sexual health’ OR | AND | ‘United Kingdom’ OR UK OR Britain OR Scotland OR England OR Wales OR ‘Northern Ireland’ |

The search was limited to peer-reviewed publications published from 1 January 2018–31 December 2023. The databases CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, SCOPUS and Web of Science were searched.

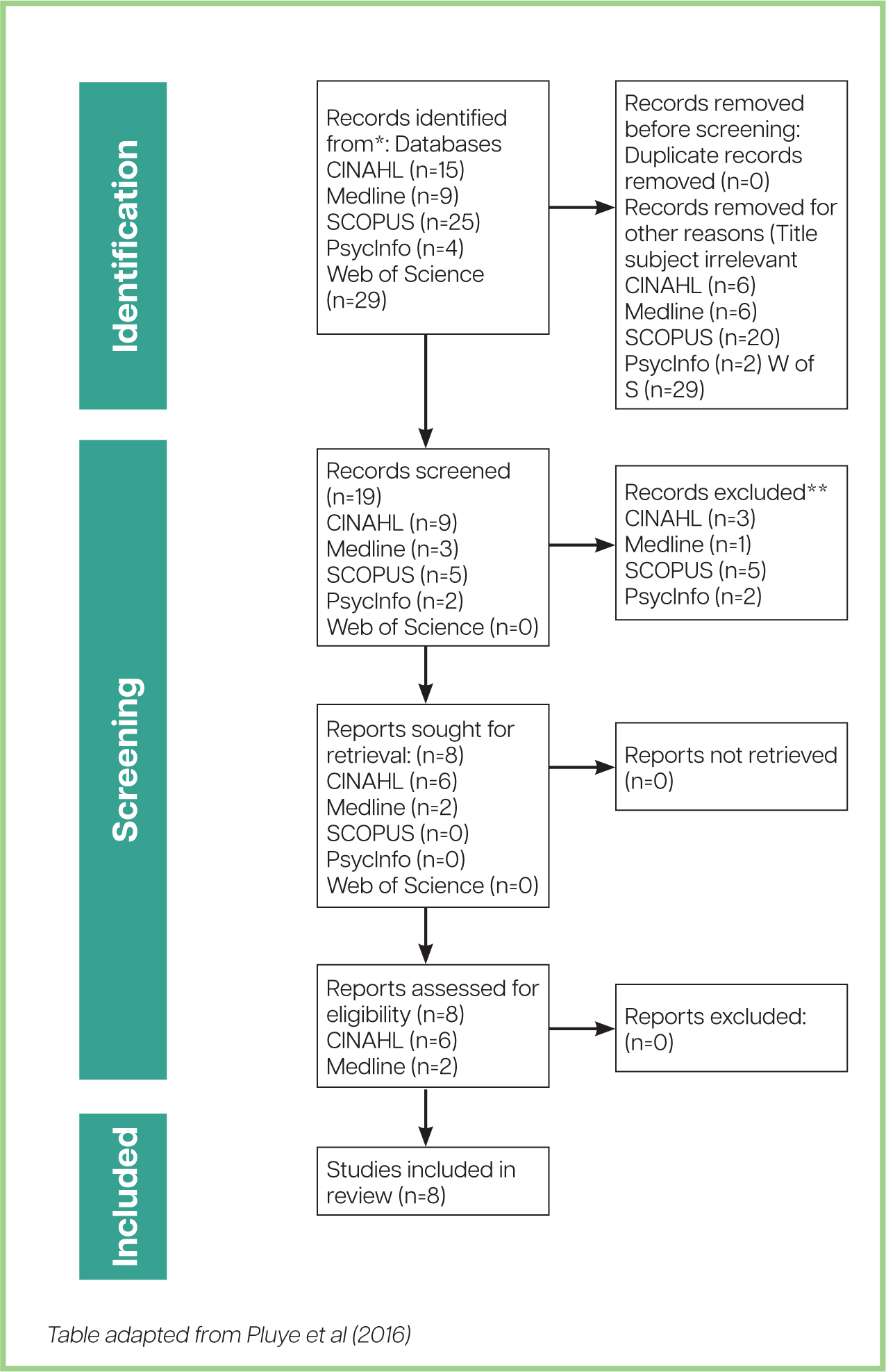

The initial search identified 82 publications. Of these, 63 were removed before screening as they were deemed irrelevant based on the title subject. The remaining 19 publications were screened by evaluating the publications' extracts against defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria consisted of studies related to school nursing practice and studies related to sexual health, mental health, or decision-making. Exclusion criteria were studies which were not UK-based, lack of evidence of research content and news items.

Screening removed a further 11 publications, leaving eight publications for retrieval and detailed analysis. A PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the selection process (see Figure 1).

The eight publications were reviewed by a detailed read of the full-text publication. Each publication was analysed using the MMAT for mixed, quantitative, and qualitative research. This tool evaluates whether there is a clear research question and analyses the findings against the research question. It also includes questions that consider potential bias (i.e. accounting for confounders, and the risk of non-response bias) (Hong et al, 2018).

The eight publications reviewed were evaluated against the criterion: Are there clear research questions? (see Table 2). This identified that five had clear research questions, one did not, and in two cases it was not clear from the article. The areas of practice researched broke down into sexual health (six publications) (Aranda et al, 2018; Beech and Sayer, 2018; Nichols, 2018; Duncan, 2019; Sisson and Wilkinson, 2019; Epps et al, 2023), and mental health (one publication) (Turner et al, 2022). In the eighth publication (Wales and Sayer, 2019), there was no specific practice area as the article was an investigation into the use of a text-messaging service between school nurses and young people. However, this study did identify that young people have highlighted emotional and sexual health as the key topics in communications with school nurses.

| Study (1st author, year) | Clear research questions? | Study design | Number of participants | Setting | Study aims |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wales (2019) | Cannot tell | Transcript analysis and survey | Conversations with young people (YP) (n=191) |

Schools in two London boroughs | To analyse a school nurse-led bidirectional text messaging service |

| Beech (2018) | Yes | Referral transaction analysis and survey | Referrals analysed (n=46) |

Schools in one London borough | To explore the role and activities of the school nursing service in sexual health |

| Aranda (2018) | Yes | Focus groups | Focus groups (n=15) |

Schools, colleges and youth centres in a south of England local authority | To explore the experiences, views and preferences of YP regarding school-based sexual health and SN |

| Turner (2022) | Yes | Scoping literature review and two-part Delphi study | Studies included (n=18) |

UK wide | To understand nurses' role in promoting children and YP's mental health and emotional wellbeing |

| Duncan (2019) | No | No study design | n/a | n/a | An overview of contraceptive methods for YP |

| Nichols (2018) | Cannot tell | No study design | n/a | n/a | Do nurses know how to respond to teenage pregnancy? |

| Epps (2023) | Yes | Rapid literature review and narrative synthesis | Studies included (n=9) | North America (n=5), Australia, UK, Ireland, Netherlands | To identify the impact of non-inclusive sex education on LGBTQ YP |

| Sisson (2019) | Yes | Integrative literature review | Studies included (n=25) | USA (n=15), Australia, Greece, Sweden, Hong Kong, Brazil, Denmark, Japan, UK | To explore what influences YP when deciding whether to receive the HPV vaccine |

Generating initial codes and identification of themes followed the thematic analysis guidance described by Braun and Clarke (2006). Initial coding identified 47 initial codes; these were grouped into two main subject areas:

The codes were then analysed to identify themes by grouping the codes into related topics. Initially, six themes were identified: health need, participation, school nurse profile, school nurse training needs, service requirements, and interventions (see Tables 3 and 4).

| Need | Participation | SN profile | Training | Service requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive sex education (n=2) | Hetrocentric SRE (n=1) | SNs able to provide accurate information (n=1) | SNs have received training to support YP sexual health needs (n=1) | Need for a mixture of single-gender, mixed-gender group conversations and 1-1 sessions (n=1) |

| Alienation from mainstream SRE (n=1) | YP participating in research (n=2) | SNs are key contributors to sexual health education (n=2) | Training for SNs needed (n=6) | Need to develop positive cultures, as well as systems, processes and practices that fully support diverse, non-normative understandings of sexual health (n=1) |

| The majority of texts received by SNs relate to sexual health (n=2) | SNs viewed as trusted professionals (n=1) | Although trained, SNs lack confidence in delivering support (n=1) | Service needs to switch from reactive to preventative (n=2) | |

| YP want contraception, and STI testing services (n=2) | SNs fundamental to promotion and delivery of HPV vaccine (n=1) | Involve YP in service design (n=2) | ||

| Promoting healthy relationships (n=3) | SNs' role and specific input to sexual health promotion appears invisible to YP (n=1) | SNs should ensure discussion should include parents where appropriate (n=1) | ||

| Informal sources of sex education (n=2) | Need to raise the profile of SNs with other agencies (n=1) | Incorporate contraception, etc. into drop-in clinics to aid preventative approach (n=1) | ||

| Fear of promoting immoral or risky behaviour (n=3) | Perceived lack of SN resource (n=1) | Gaps and regional differences (n=2) | ||

| Risk of STIs (n=3) | SN service underutilised (n=1) | |||

| Risk of pregnancy (n=4) | ||||

| School staff not perceiving sexual health to be an area of need (n=1) | ||||

| Addressing risky sexual behaviour (n=1) |

| Need | Participation | SN profile | Training | Service requirements | Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional health is the most common type of query being received from YP and the topic SNs feel least confident in responding to (n=1) | Participation of parents (n=1) | The nature of an SN role is likely to be more proactive and educational (n=1) | Training in therapeutic interventions would strengthen the input of SCPHN practitioners (n=1) | Provide counselling about emotional implications of sexual activity (n=1) | Nurse-led early interventions addressing the MH and emotional wellbeing needs of YP were being extensively utilised (n=1) |

| It is important for SNs to feel confident in supporting YP with emotional health concerns (n=1) | Inequalities exist in delivery of interventions (n=1) | Nurses should be able to train in effective models for YP's mental health and wellbeing (n=1) | A third of existing services for YP are inadequate (n=1) | ||

| Understand what influences decision-making in YP (n=1) | |||||

| Emotional wellbeing significant factor in sexual health (n=2) | |||||

| Factors influencing decision making (n=1) | |||||

| Mental health issues in YP reached crisis level (n=1) | |||||

| COVID has increased demand (n=1) | |||||

| YP emotional wellbeing is suffering (n=1) |

Grouping the codes against these initial themes led to further refinement as it became apparent that there was insufficient data to support some themes, and codes corresponded closely across more than one initial theme (Braun and Clarke, 2006: 16). The blank initial codes were either simple statements of fact or too specific to the subject of the individual publication (e.g. the HPV vaccine). This resulted in four themes:

| Roadblocks to effective delivery | SN training needs | YP needs and participation | Delivery of proactive interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| SN's role and specific input to sexual health promotion appears invisible to YP (n=1) | SNs have received training to support YP sexual health needs (n=1) | YP want contraception, and STI testing services (n=2) | Need to develop positive cultures, as well as systems, processes and practices that fully support diverse, non-normative understandings of sexual health (n=4) |

| Need to raise profile of SNs with other agencies (n=1) | Training for SNs needed (n=6) | The majority of texts received by SNs relate to sexual health (n=2) | SNs are key contributors to sexual health education (n=2) |

| Perceived lack of SN resource (n=1) | Although trained, SNs lack confidence in delivering support (n=1) | YP participating in research (n=2) | |

| Gaps and regional differences (n=2) | Training in therapeutic interventions would strengthen the input of SCPHN practitioners (n=1) | Involve YP in service design (n=2) | Incorporate contraception etc. into drop-in clinics to aid preventative approach (n=1) |

| SN service underutilised (n=1) | Nurses should be able to train in effective models for YP's mental health and wellbeing (n=2) | Inclusive sex education (n=2) | |

| School staff not perceiving sexual health to be an area of need (n=1) | Need for a mixture of single-gender, mixed gender group conversations and 1:1 sessions (n=1) | Service needs to switch from reactive to preventative (n=2) | |

| Inequalities exist in delivery of interventions (n=1) | Emotional health is the most common type of query being received from YP and the topic SNs feel least confident in responding to (n=1) | Provide counselling about emotional implications of sexual activity (n=1) | |

| Informal sources of sex education (n=2) | Understand what influences decision-making in YP (n=1) | ||

| Fear of promoting immoral or risky behaviour (n=3) | YP emotional wellbeing is suffering (n=1) |

Results

Roadblocks to effective delivery of school nurse provision

Four of the publications (Aranda et al, 2018; Beech and Sayer, 2018; Turner et al, 2022; Epps et al, 2023), identify some sort of roadblock or obstacle to school nurses delivering services. Two of the studies (Aranda et al, 2018; Beech and Sayer, 2018), were specifically focused on understanding the current provision of sexual health services and education, and the role of school nurses. The third study (Epps et al, 2023), investigated sex education for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people, while the fourth (Turner et al, 2022) looked at interventions for young people's psychological wellbeing.

One study (Beech and Sayer, 2018) surveyed school nurses and school staff. This study identified the most roadblocks, including:

The second study focused on sexual health provision (Aranda et al, 2018). It surveyed young people for their perceptions of sexual health and school nursing. The main roadblock identified in this study was the invisibility of the school nurse service to young people.

The third study investigated the sex education experiences of LGBTQ young people (Epps et al, 2023). This study started from the premise that sex education in schools is ‘predominantly heterocentric. Consequently, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning young people have reported feeling excluded.’ (Epps et al, 2023: 87). The roadblocks identified were:

The fourth study investigated provision of nurse led interventions for young people's psychological wellbeing (Turner et al, 2022).

The findings of this study were generally more positive about provision than those focused on sex education. However, the issue of inequalities in the provision of the service was identified, concluding that programme delivery is ‘heavily dependent on the skills of individual practitioners’ (Turner et al, 2022: 93).

School nurse training needs

One article, focused on contraceptive services for young people (Duncan, 2019), does not mention training. This leaves seven that mention or discuss training to some extent (Aranda et al, 2018; Beech and Sayer, 2018; Nichols, 2018; Sisson and Wilkinson, 2019; Wales and Sayer, 2019; Turner et al, 2022; Epps et al, 2023).

Two of the studies that mention training imply that school nurses are sufficiently trained, and it is other school staff that require the training (Aranda et al, 2018; Epps et al, 2023). It is notable that these studies did not engage with school nurses in their investigation. From their description of methods, one involved a survey of young people's experience of SRE and school nurse services (Aranda et al, 2018), and the other was a literature review based on young people's experiences of SRE (Epps et al, 2023).

The remaining five studies (Beech and Sayer, 2018; Nichols, 2018; Sisson and Wilkinson, 2019; Wales and Sayer, 2019; Turner et al, 2022), identify school nurse training as an important or critical aspect of delivering the service. Three of these studies involved surveys of school nurses (Beech and Sayer, 2018; Wales and Sayer, 2019; Turner et al, 2022). Beech and Sayer (2018: 294) note that, while all school nurses surveyed had received training in sexual health, they felt further training was required and this ‘was the main need reported’. The investigation into the use of a text-messaging service (Wales and Sayer, 2019) covered the full range of school nursing interventions. It is notable that the aspect of the service which school nurses felt most challenging, and therefore the greatest training need, was ‘responding to emotional health queries’ (Wales and Sayer, 2019: 129).

A literature review (Sisson and Wilkinson, 2019) of studies into young people's experiences with the HPV vaccine mainly focused on the attitudes of young people and their parents. Some of the studies reviewed did include the views of nurses, although these were based in Australia and the United States. Among the key findings, the study states that school nurses should recommend HPV vaccine and ‘This requires being up to date with any associated training, so that accurate information can be delivered with competence and confidence’ (Sisson and Wilkinson, 2019: 47); however, it is not clear whether this assertion is based on the study's results.

The final article, which amounts to a general discussion of how to tackle teenage pregnancy, mentions training on relationships and sexual health, but only in a diagram illustrating ‘10 factors for successful teenage pregnancy reduction’ (Nichols, 2018: 20). There is no further elaboration on this factor in the remainder of the article.

Young people's needs and participation

Two of the articles do not discuss young people's expressed health needs, or their participation in the design of the school nurse service (Duncan, 2019; Turner et al, 2022). One article acknowledges that ‘Young people have been calling for more help navigating the difficult world of sexual relationships for some time’ (Nichols, 2018: 21), but does not offer any evidence to support this assertion.

The remaining five studies (Aranda et al, 2018; Beech and Sayer, 2018; Sisson and Wilkinson, 2019; Wales and Sayer, 2019; Epps et al, 2023) include more extensive discussion of young people's engagement in the school nurse service. It is notable that four of these studies either canvas the views of young people directly (Aranda et al, 2018), through literature reviews of studies of young people's attitudes (Sisson and Wilkinson, 2019; Epps et al, 2023), or indirectly by analysing the content of text messages sent to school nurses (Wales and Sayer, 2019). One study is mainly focused on young people's attitudes to the HPV vaccine but notes that there is ‘a need for school nurses to involve adolescents and parents as much as possible in the decision-making process’ (Sisson and Wilkinson, 2019: 47).

One of the main findings that emerges from the young person-focused studies is that engagement between young people and school nurses is lacking, or young people do not see how the service provides for their needs. Wales and Sayer (2019: 128), identified that only 0.8% of young people in the London boroughs surveyed were using the ChatHealth messaging service to communicate with school nurses. Although young people express a definite need for sexual health education and support, ‘provision was deemed fairly ineffective, inappropriate or unacceptable to young people’ (Aranda et al, 2018: 382), and ‘LGBTQ young people feel that they were left unprepared for their relationships and sexual lives, the education they received perceived as being irrelevant to them’ (Epps et al, 2023: 92). Aranda et al (2018: 382) highlighted that ‘our findings show little has changed and that challenges remain regarding young people and school-based sexual health services and school nursing’.

The main recommendation of these studies is that those commissioning or designing the school nursing service need to listen to what young people want, if the service is to add value. Typical conclusions are that ‘Young people should be consulted on their views of what to include and how to deliver sexuality education at school to ensure a fully inclusive curriculum’ (Epps et al, 2023: 95), and that a shift in approach ‘would involve schools and school nurses especially prioritising the participation of young people to enable their values, norms and beliefs be heard’ (Aranda et al, 2018: 382).

Delivery of proactive interventions

There is a general view in most of these studies that the school nursing service needs improvement based on the challenges faced in sexual and mental health, and the lack of engagement with young people. All but one of the studies (Nichols, 2018), make at least one recommendation for proactive interventions by school nurses in response to the needs of young people.

In sexual health, it is noted that provision is predominantly reactive and one study advocates ‘a more preventative approach with both SNs and school staff outlining a vision for future service development that includes greater SRE, condom distribution and targeted group work’ (Beech and Sayer, 2018: 297). Another study suggests that school nurses ‘need to develop positive cultures, as well as systems, processes and practices that fully support diverse, non-normative understandings of sexual health’ (Aranda et al, 2018: 383). Similarly, in addressing psychological wellbeing, a study recognises that there are examples of excellent practice but that there is no uniform provision and that programmes are ‘heavily dependent on the skills of individual practitioners’ (Turner et al, 2022: 93).

The consensus is that input from young people is essential to the development of proactive or preventative programmes. In discussing the further enhancement of a text-messaging service, the conclusion is that ‘robust and creative promotional campaigns involving YP in the design and implementation is likely to assist in the uptake of the service’ (Wales and Sayer, 2019: 130). In meeting the SRE needs of LGBTQ young people, youth participation and student evaluation will help ‘educators keep up with their students, hear their views, and adapt their teaching to the topics young people feel they need to know within their generation's cultural climate’ (Epps et al, 2023: 95).

Discussion

There is a paucity of literature about the school nursing service related to the topics of sexual and mental health between 2018 and 2023. Even within the eight studies returned there is only one that describes a new initiative, namely the use of a text-messaging service (Wales and Sayer, 2019). Some of the studies describe established procedures such as contraception and vaccination. The remainder review the existing provision of sexual and mental health services and come to the conclusion that more needs to be done in order for the school nursing service to really impact on provision for young people (Aranda et al, 2018; Beech and Sayer, 2018; Nichols, 2018; Turner et al, 2022; Epps et al, 2023). This implies that there has not been much progress on the issues researched in the author's publications. This is reflected by the statement that ‘our findings show little has changed and that challenges remain regarding young people and school-based sexual health services and school nursing’ (Aranda et al, 2018: 382).

However, key themes have emerged in the review. Young people want a service that is ‘present and available, but private and discrete’ (Aranda et al, 2018: 382). They also want a service that reflects the changing identity of youth today. Rejection of stereotypical norms through inclusive and challenging practice protects young people and enables them to fulfil their potential (Aranda et al, 2018; Epps et al, 2023).

Young people's needs are clearly articulated when they are given a voice. They want school nurses involved in their lives. ‘Do you care about seeing the school nurse, would you want to see them more? It would be nice to know she was there’ (Aranda et al, 2018: 380).

Limitations

The literature review undertaken only identified eight articles that met the search criteria. This makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the direction of travel of the school nursing service. It is entirely possible that initiatives are being undertaken which have not yet been published.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have had an impact on progress, both in school nurses having to adjust their practice and potentially having less time to devote to research. Of the eight studies appraised in this review, six were published in 2018-19, and only two in the 4 years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is notable that the initial search of school nursing publications returned some that were specifically focused on the impact of COVID-19 on school nurses. This includes school nurses' involvement in the COVID-19 vaccination programme (Evans, 2021) and new ways of working because of the pandemic (Cook et al, 2023).

Conclusion

Progress in school nurse innovations has stalled. The lack of initiatives may be due to reduced resources and the pandemic. However, it may be that external influences are masking fundamental issues concerning confidence and identity in school nursing practice. Erosion of the public health aspects of the school nurse role to fill gaps in service has led to reactive and ineffective practice.

A call to action for school nurses to build on the past and reshape the role for the future should be based on what young people need and want. The response to a request I received 20 years ago: ‘Can we have them lessons again?’ (Day, 2004: 178) should be ‘Yes, you can’.