In the United Kingdom, cancer affects one in every 500 children under the age of 15 (Office for National Statistics, 2020), the most common types being leukaemia and brain tumours. Children's community nurses (CCNs) are a group of professionals working together alongside principal treatment centres (PTC) and local shared care units to provide care. The CCNs aim is to reduce hospital visits, reduce infections and try where possible to help the child to live as normal a life as possible (The Queen's Nursing Institute, 2018). Episodes of care often included administering intravenous antibiotics and chemotherapy, wound management, phlebotomy and enteral feeding. However, at present there is no framework for CCN teams, particularly in relation to cancer care, therefore CCN services throughout the UK vary.

Background

There are many advantages of receiving care in the community, be that in an educational setting or at home (Green, 2019). Children undergoing cancer treatment and families want to feel a sense of normality by attending school and seeing friends, and parents want to continue working (Hansson et al, 2012; Darcy et al, 2019). Both parents and children may at times feel isolated and lonely, as a result of attending multiple appointments and having long admissions for treatment, or due to complications (Bjork et al, 2009; Gibson et al, 2010; Darcy et al, 2019). Support from CCN teams can have a positive impact on the child and family's quality of life, children were able to be seen at a time suitable for them and their family (Castor et al, 2017). Support from a CCN team can reduce pressures on the family, both emotionally and financially (Green, 2019).

However, there is a paucity of literature identifying what procedures or treatments were carried out by CCNs in the community (Green, 2019). Most of the studies were European and were therefore not generalisable to the UK due to dissimilar health services.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to highlight the experiences of CCNs within cancer care and to identify their day-to-day roles and responsibilities.

Methods

Initially, both quantitative and qualitative research methods were explored, however quantitative methods require a large number of participants for the research to be truly valid and generalisable (Parahoo, 2014; Boswell and Cannon, 2016; Borbasi et al, 2019). It was decided that the research would benefit from experiences to allow a deeper interpretation of the data, which would be gained through a qualitative study (Polit and Beck, 2017; Houser, 2018). A purposeful sample group was chosen because as Lathlean (2015), Parahoo (2014) and Luciani et al (2019) explain, it is the most effective way of extracting specific information from participants in nursing research and maximises the efficiency of the data collection. CCNs and specialist shared care oncology nurses were identified as suitable participants. Children and families were excluded from the study due to ethical dilemmas such as consent (Institute of Medicine, 2004).

Table 1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

|

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to determine the participants' ability to answer the research questions (Borbasi et al, 2019; Tappen, 2011). The sample area was defined as the 12 inner boroughs of London. Due to small scale research study and to research within personal limits

Focus groups, interviews and questionnaire methods were originally explored; however, it was decided that focus groups and interviews would have been costly in time to transcribe (Boswell and Cannon, 2016; Houser, 2018). A questionnaire was chosen to capture self-reported observations, which as Jones and Rattray (2015) and Wood and Kerr (2011) agree can be electronically sent to a large volume of participants, few costs are involved and they can easily be analysed using coding software. Coding software was used to streamline data collection and ensure efficiency of the data analysis. Initially, 14 open-ended questions and 1 tick box closed question (the latter was used to gather quantifiable data to strengthen the findings) were created. However, following peer review and discussion, 12 questions were finalised. These reviewers did not participate in the study.

No private, non-NHS funded CCN teams were identified in the sample area of central london. Five CCN teams from within the 12 inner London Boroughs were identified as the sample group, emails or phone calls were made to each service lead to discuss consent for participation.

Four of these teams consented for the questionnaires to be sent via email, the fifth did not respond. Three oncology specialist nurses within the area also consented to be part of the study. Questionnaires were sent electronically via secure email to the participating teams. Nine CCNs and three specialist nurses returned the completed questionnaires which were analysed using MAXQDA (2020) software. In Vivo coding and thematic analysis were used to systematically process, identify and analyse the data from the questionnaires (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Manning, 2017; Saldana, 2016).

Ethical considerations

In addition to the questionnaire circulated, an information document was given to all participants to ensure the research intentions were understood and that confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed. The document instructed that no information making patients or families identifiable should be used and returned questionnaires should not be personally named so that the researcher could not link any response with a participant. Furthermore, all completed questionnaires were stored on a password protected electronic device, stored in a locked cupboard when not in use. Participants were informed at the beginning of the study that they would be able to withdraw at any point without consequence.

Ethical approval was granted by the ethics committee within Buckinghamshire New University and supported by Central London Community Healthcare Trust.

Findings

The main themes identified through the findings include:

- Roles and responsibilities

- Positive feedback

- Maintaining normality through treatment

- CCN experience and education

- Limited chemotherapy treatments available to give safely in the community.

Roles and responsibilities

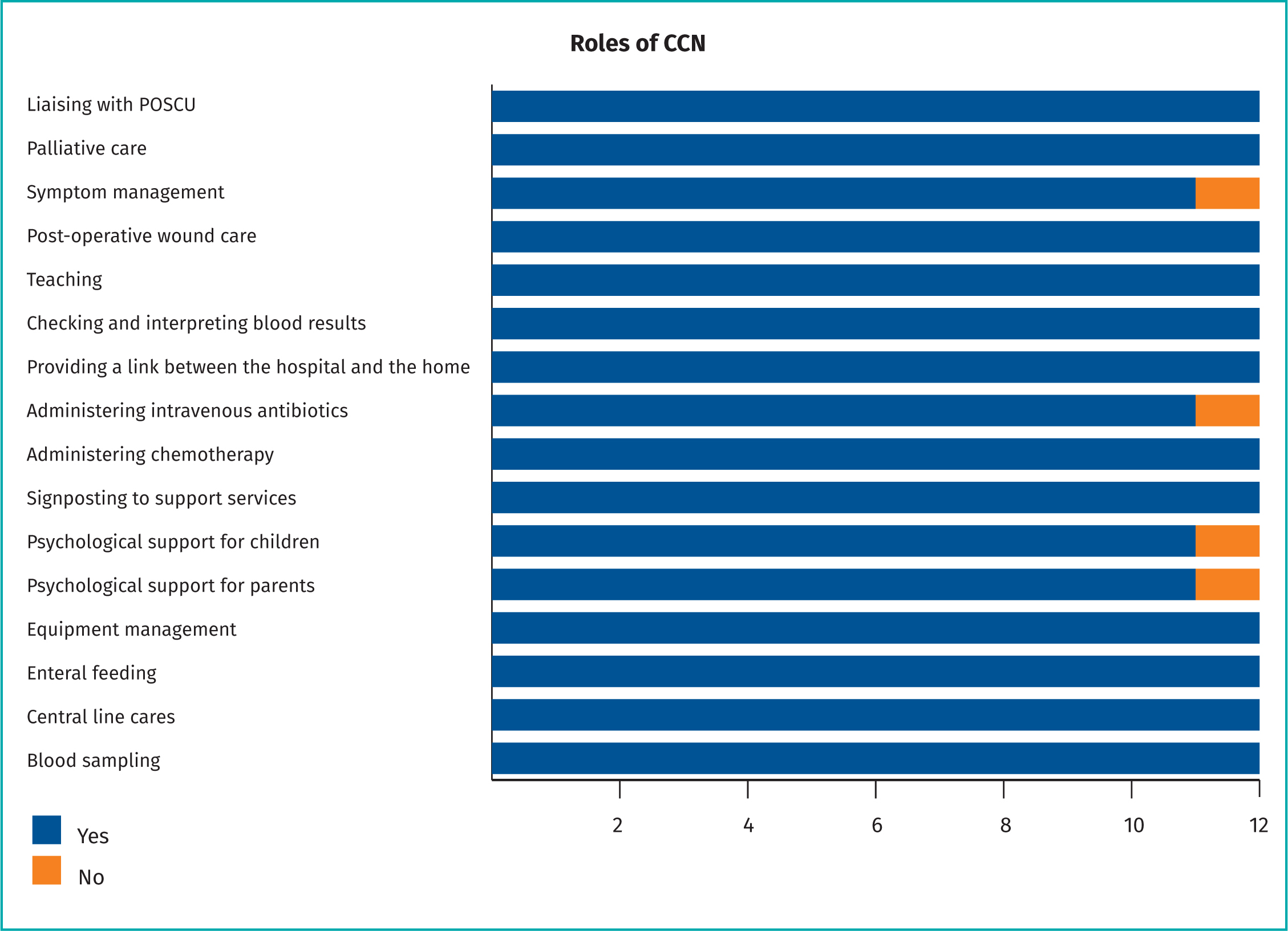

Table Two exhibits the statistical findings for Q12, which asked each participant to tick the appropriate episode of care carried out by the CCN relating to cancer care. This data was then analysed and found to be consistent with the qualitative responses from Q1-11 and led to the framework being developed.

In answer to one question, ‘In your opinion, why are children with cancer visited by a children's community nurse?’ participants of varied job roles answered with consistency.

‘To avoid them having to go into hospital for episodes of care that can be provided at home.’

Participant K, CCN Team Lead

‘To limit hospital attendances, to obtain blood samples and give certain chemotherapy, carry out line cares, provide symptom management support, support with enteral feeding.’

Participant J, CCN Team Lead

‘To prevent them needing to attend hospital for routine procedures like blood sampling or dressing changes or medications’.

Participant D, CCN

‘Minimise time children have to spend in hospital. They can have “normal” routines school etc. while having nursing cares attended to. Less disruptive to family life.’

Participant L, Oncology Specialist Nurse

The questionnaire collected data for which specific skills and cares were carried out by CCNs on a day-to-day basis. The formulation of a standardised framework would ensure these episodes of care are delivered with consistency across NHS trusts.

One hundred percent of participants agreed that part of a CCNs role is liaising with POSCU (Paediatric Oncology Shared Care Units); when asked, ‘What do you understand by the term POSCU?’ responses were similar, which showed consistency of the knowledge and understanding of the role of POSCU. Eight of the 12 participants agreed POSCU was a form of multidisciplinary working including PTC (Principal Treatment Centre) and local hospitals and six participants mentioned the primary role of ensuring care is available close to home, two specialist nurses highlighted this is usually within 1 hour of the child's home. In response to this question, one CCN (Participant B) wrote:

‘This is the local team which supports the child when not being cared for by their main tertiary centre, they provide some treatment locally which keeps the child closer to home and helps reduce the pressure on the larger centres of care’.

Participant H, a specialist oncology nurse wrote:

‘A hospital that works in conjunction with the PTC and provides supportive care closer to home’.

Nine of the 12 participants similarly acknowledged that children and their families travel considerably less than if they were required to attend the PTC for their treatment, enhancing their quality of life, which highlights the importance of community care.

Positive feedback

According to Hansson et al (2011) and Darcy et al (2019), children are happiest when they are cared for at home where their families and parents are less stressed or anxious. Therefore, it is important to understand how community services are perceived by asking about the experiences of the nurses working within the homes and in the hospitals, reviewing the consistencies or inconsistencies. When asked, ‘How do you think the children and their families perceive the service given by Children's Community Nurses?’ All 12 participant answers were positive, the most common word used was ‘grateful’. Participant C wrote,

‘Wonderful service, very helpful, great team’. Others wrote helpful, friendly, knowledgeable, approachable, respectful, happy, fun, flexible, consistent, family-friendly and supportive.’

Similarly, specialist nurses confirmed from their perspectives, adding to the validity of the results, being from separate teams who are less likely to be biased. Participant L, a specialist nurse wrote:

‘always get excellent feedback and express how grateful they are for the service’.

Participant H, specialist nurse, also stated:

‘They appreciate it, mostly all of the families that use our service say they are grateful for the service we provide, that they didn't have to go to the hospital all the time.’

These statements are in line with Carter et al (2012) and Castor et al (2018) who found similar supporting themes.

Maintaining normality through treatment

Having understood the CCN service is appreciated by families, it is important to understand why. Being able to maintain children and their family's routine was one theme which emerged throughout the questionnaires and in previous literature (Bjork et al, 2009; Castor et al, 2018; Darcy et al, 2014) highlighting that CCN visits to school, nurseries, after-school clubs or attending before school to complete episodes of care contributed to this. Participant E, a CCN, stated the service ‘enhances their quality of life by making it possible for them to do their daily norms’. Participant A wrote:

‘Many people are grateful we are able to treat their child/themselves (teenagers) at home/school. They value the time they are able to spend with their children within their homes, establishing daily routines and normality’.

Similarly, Participant B wrote:

‘Parents and families can have a sense of normality and continue with normal daily living i.e. attend school as CCNs can see them there.’

These quotes all depict a similar idea that CCN teams are positive in promoting normal daily activities for the child and the family.

To ensure children are cared for safely in the educational setting, a select group of teachers, assistants and first aiders are offered training in how to support the child. This includes the safety of the Central Venous Access Device (CVAD), emergencies and basic understanding of the child's condition. Participant E wrote:

‘Providing training with the school so he/she is safe.’

Participant K also agreed by writing:

‘Provide Hickman line training, training the teacher and other staff members what to do in an emergency.’

If the child requires extra learning support, an Education and Healthcare Plan (EHCP) will be introduced, with which the CCN will provide information. Participant E conferred ‘Complete an EHCP if required’.

Travel time was consistently noted throughout the questionnaires, exploring the positive aspect of community care which reduced hospital travelling time, reducing possible infections acquired from taking public transport and the cost of taxis. Six participants explored this in their answers. Participant E wrote:

‘Parents have to rely on family friends to pick up the sibling from school or the sibling gets taken out of school as well, CCN services take the pressures away from the parents.’

Participant G also noted:

‘Parents fear child will pick up infections on public transport and it is expensive to travel in taxis.’

CCN experience and education

Most of the findings were positive in gaining a clear direction of the skills, responsibilities and episodes of care carried out by CCNs, especially by using the quantifiable answers from Question 12. However, a theme emerged highlighting a difference in the amount of CCNs who had ticked yes to the administration of chemotherapy in the community being their role, and the five out of eight CCNs who had completed the relevant competencies to enable this. Positively, though, six out of eight CCNs had attended a POSCU study day which would have given them the knowledge and understanding surrounding cancer treatments. As well as this, it was evident that having good knowledge impacts care given to patients and impacts the CCNs ability to recognise problems to do with their treatment such as side effects of chemotherapy.

When asked, ‘What are the disadvantages of receiving care in the community?’ Participant H wrote:

‘Often a problem can arise for example a sore throat. It would be helpful to have certain bloods taken or swabs but this cannot be done if the equipment/bottles are not taken. Depends on the level of expertise of the nurses caring for the child in understanding the symptoms and concerns.’

Similarly Participant J wrote:

‘some staff are not familiar with cancers/leukaemia and so less knowledgeable of treatment plans/side effects.’

These comments imply a requirement for all CCNs to undertake sufficient education so that there is consistency in the care given to patients in the community, and to ensure best practice. These statements are supported by similar findings from Hansson et al (2012), Randall (2012) and Whiting et al (2015) who imply the need for further education to ensure all community staff have adequate knowledge of the child's condition.

Limited chemotherapy treatments available to give safely in the community

Cytarabine is the most common chemotherapy given to children in the community, however, this service is not available for all and results in many children attending hospital. This is mainly due to the skill mix of staff and service working hours, three participants including two nurse specialists and a CCN team lead noted additional chemotherapies could be given in the community if safe. When asked, ‘Are there any services CCN teams could provide to children with cancer that they do not currently?’ Participant K wrote:

‘not unless there were other chemotherapies that were suitable for being administered at home’.

Participant F noted this is happening within another team in London. However, this team did not partake in this research:

‘I am aware that some CCN teams who include ANP (advanced nurse practitioner) are able to fit for chemotherapy who are trialing IV vincristine in the community’.

The nurse also added:

‘not all CCN teams are chemo givers/work weekends + bank holidays so the service can be very variable amongst teams.’

These quotes suggest a variation in services, which could be improved by educating staff and adopting a framework to ensure practice is consistent.

Discussion

The QNI (2018) has highlighted the standards for CCN education and practice, which aligns with the vision set out in this framework to ensure CCNs area adequately equipped to treat, manage and support with the episodes of care highlighted in Figure 1. Training needs should be taken into account to ensure best practices are carried out in all CCN services.

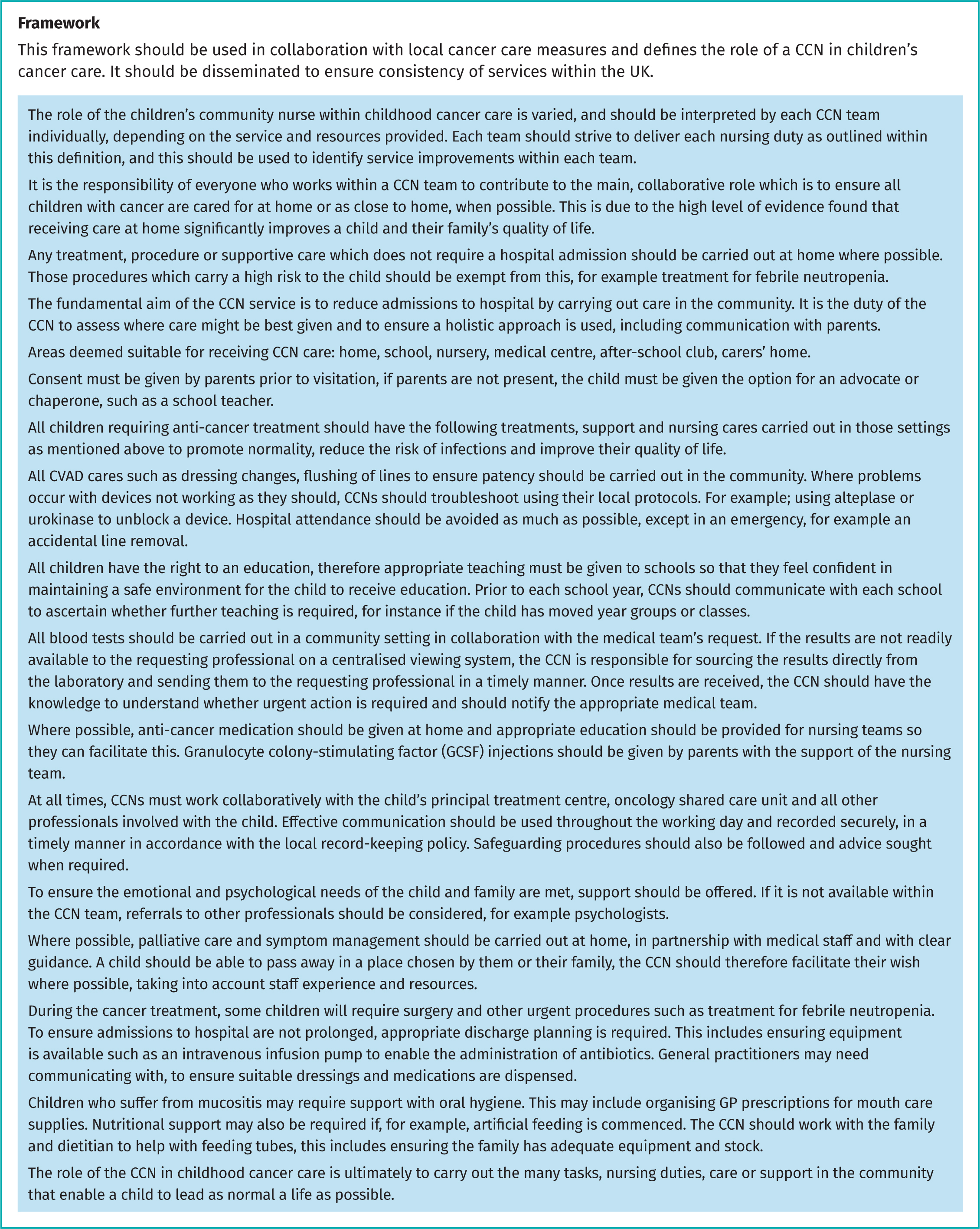

Previous research studies and the participants in this study agree that care given at home or as close to home as possible benefits the child and family, helping to maintain some normality throughout their treatment and families appreciate not having to go to hospital (Castoret al, 2017; Carteret al, 2012; Gibsonet al, 2010). Having said this, some participants reported variations between services. To improve consistency, a standardised framework would be of benefit (Moulin et al, 2015) and as a result of the analysis of the research, recommendations have been made to improve practice (Figure 2).

Limitations

Although CCNs were the chosen participant group for this study for the purpose of obtaining specific information as suggested in the literature (Luciani et al, 2019), there is a risk of bias. CCNs might not want to openly share negative feedback especially in relation to advantages and disadvantages of care in the community. This was minimised by ensuring anonymity, however, and caution was taken while reviewing the questionnaires. The participant group was restricted to a relatively small area of the UK, but because of the large population size with varying demographics, the research was deemed generalisable to the UK in areas that have access to community nursing teams. In addition, the response rate was poor at 5.76%. Having decided to send the questionnaire via electronic means to the teams' shared email system, this relied on the questionnaires to be disseminated out and to be sent back via email. In hindsight, an electronic questionnaire might have appeared easier and quicker to complete, likely increasing the response rate.

Conclusions

Using questionnaires, this research highlighted participants' views and experiences surrounding CCNs and the services provided. Data analysed using MAXQDA identified consistencies and inconsistencies in the episodes of care carried out by CCNs and highlighted the need for standardisation across CCN teams, which would be assisted by a standards framework. This would ensure all children and young people have access to community care, minimise hospital admissions and ultimately reduce infections, improving quality of life.

Recommendations

- All CCNs should attend a POSCU study day (or equivalent) within 6 months of joining a CCN team. This is to ensure the consistency of knowledge between all staff members, to increase confidence with spotting oncological emergencies, to reduce parental anxieties and to ultimately provide safe practice. A 3 yearly update is also recommended as treatments and guidelines change regularly.

- Consistency between CCN services should be improved by working towards a standards framework, to ensure all children undergoing treatment for cancer have access to care at home or as close to home as possible. The proposed framework has been peer reviewed by one senior team lead and one specialist service manager for a CCN team in Central London during this research process. Therefore, the framework will require further consultation with community services and agreed in line with shared care facilities prior to its implementation, as well as piloting.

- Once the framework has been agreed and implemented, further study is necessary to evaluate the use of the framework and to assess its effectiveness. This would be carried out in the form of a service evaluation encompassing the experiences of CCNs, specialist nurses and if ethical approval is sought, children and their family's experiences would also be favourable.

KEY POINTS

- CCNs are pivotal members of the multi-disciplinary team surrounding childhood cancer care and the patient's journey to recovery.

- A standardised framework would benefit patient care, if followed, by ultimately reducing admissions to acute care and reducing hospital-acquired infections.

- The quality of life for both the child and family is positively affected when a CCN team is available to them by allowing families to gain some normality in such difficult times.

- Services across London are varied, for example cytarabine is available in some CCN teams but not in others. More training is required for those CNN teams who do not currently offer this service to ensure care is standardised across London.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- What can health-care organisations learn from this study?

- What further research is required to enhance the validity of this research?

- How can we put this framework into practice?