Job satisfaction can be defined as the attitude and feelings individuals experience about their work. Job satisfaction has a strong relationship with mental and physical health. People who are more satisfied with their work are happier and healthier. Job satisfaction contributes to better work outcome and productivity and reduces nurses' absenteeism and turnover (Satuf et al, 2018; Ozdoba et al, 2022).

Job satisfaction is a prerequisite for efficient nursing, especially when working with children and particularly children with complex chronic health problems or who are critically ill, for whom extensive knowledge and skills are required (Bratt et al, 2000; Bleazard, 2020; Kaya and İşler Dalgiç, 2021).

Thus, it is important to search for factors affecting job satisfaction in various countries and settings in order to optimise the care of sick children. Literature data indicate that nurses' professional satisfaction and quality of life are influenced by age, gender, family status, salary, educational level and future prospects. Not less, prior nursing experience, the type of working unit, the relationship with colleagues and patients, as well as the cyclic programme of working hours constitute contributory factors to their satisfaction or dissatisfaction. These factors have been evaluated in various settings in different studies (Bratt et al, 2000; Robins et al, 2009; Ibrahim et al, 2016; Nowrouzi et al, 2016; Khosrojerdi et al, 2018; Satuf et al, 2018; Bleazard, 2020; Kagan et al, 2021; Kiliç Barmanpek et al, 2022).

The amount of years worked can have a negative impact and be related to psychological exhaustion. However, many studies showed that previous work experience, in the same institution, increases self-confidence and ability to handle more stressful conditions, thus increasing the level of their quality of life (Bratt et al, 2000; Robins et al, 2009; Branch and Klinkenberg, 2015; Ibrahim et al, 2016; Nowrouzi et al, 2016; Moradi et al, 2017; Allan et al, 2018; Khosrojerdi et al, 2018; Satuf et al, 2018; Bleazard, 2020; Kaya and İşler-Dalgıç, 2020; Kagan et al, 2021).

Nurses working in paediatric hospitals experience higher percentages of fatigue, professional exhaustion and lower psychological satisfaction, especially those working in intensive care units, or haematology/oncology departments. About 30% of nurses working in units of neonatal emergency care reported symptoms of professional burnout and nurses working in paediatric intensive care units reported lower percentages of satisfaction and higher percentages of fatigue and anxiety (Branch and Klinkenberg, 2015). Harmonious relations with colleagues working together attenuate working anxiety and increase professional satisfaction, resulting in improved effectiveness of nursing interventions (Ibrahim et al, 2016; Nowrouzi et al, 2016; Khosrojerdi et al, 2018, Blixt et al, 2023).

Regarding the effect of age, there is no consensus in the literature. Specifically, in certain studies, age did not significantly affect professional satisfaction, whereas in others it was shown that nurses older than 50 years experienced greater satisfaction from their work (Ferrens, 1960; Richardson et al, 2016).

As expected with COVID-19, mental health problems of heath-care workers (HCW) and especially nurses worsened. Pertinent studies have been published for HCW taking care of adults with COVID-19 but they are quite scarce for paediatric nurses. This is most likely due to the fact that the prevalence of COVID-19 was quite low in children and of milder severity (Dong et al, 2020). Despite this fact, nurses taking care of children with COVID-19, proven or suspected, manifested high frequency of relevant symptoms, depression (39.1%), anxiety (47.7%) and stress (24.7%) among the frontline paediatric HCW during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kirk et al, 2021). Hence, paediatric nurses caring for children with COVID-19 are also at high risk for mental health symptoms to the same degree as those caring for adults with COVID-19. In other words, the psychopathology is, most likely, independent of the disease burden.

Aims

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the degree of professional satisfaction in nurses working in paediatric hospitals of tertiary care, as well as the factors affecting these parameters in Greece.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted during a 5-month period (January – May 2021) in two paediatric hospitals located in the Athens metropolitan area (i.e. Aghia Sofia Children's Hospital with 693 beds and Panagiotis and Aglaia Kyriakou Children's Hospital with 424 beds). Power analysis of 0.8 with p<0.05 was used to determine the sample size. Overall, the questionnaire was handed to 278 health professionals, of which 176 responded (response rate 71%). The inclusion criteria were:

Exclusion criteria were psychological problems. The study was taking place during a period of economic recession in Greece, which is very likely to have affected the general psychological state of the people who took part in the survey, with a related effect on job satisfaction (financial earnings) and quality of life in general and despite the satisfactory number of the sample there were disproportions in the individual categories formed by the sample. The majority of the nurses were female, the majority of the participants had a technological education and only two nurses held a PhD. As a result of these, in some cases comparisons were made between smaller and larger groups of participants. For this reason, an attempt was made to create larger categories to simulate the number of groups to be compared.

Data collection

The Measure of Job Satisfaction (MJS) questionnaire, created by Traynor and Wade was used to measure and assess nurses' job satisfaction, after permission was obtained (Traynor and Wade, 1993). The questionnaire consists of two parts. The first part is about the demographic information of the nurses (age, gender, education level, work department, marital status, and years of experience), and the second part includes 43 questions that address various aspects of their work. Six questions (questions 21, 27, 28, 30, 38, 39) refer to nurses' personal satisfaction with their work with Cronbach's α=0.85; 8 questions (questions 6, 14, 15, 20, 23, 24, 37, 40) assess nurses' workload, with Cronbach's α=0. 88, questions 2, 3, 10, 13, 22, 29, 35 and 42 assess nurses' satisfaction with professional support, with Cronbach's α=0.89, while five questions (questions 5, 18, 19, 26, 31) refer to satisfaction with in-service training, with Cronbach's α=0.85. Satisfaction with remuneration is evaluated through four questions (questions 1, 4, 9, 36) with Cronbach's alpha=0.90, satisfaction with future prospects is evaluated with six questions (questions 12, 16, 25, 32, 34, 41) with Cronbach's α=0.88. Finally, satisfaction with care patterns is assessed through six questions (questions 7, 8, 11, 17, 33, 43), Cronbach's α=0.90. At the end of the questionnaire, there is an additional question (44), which assesses the degree of overall satisfaction with the nurses' work. All the questions are evaluated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (5=very satisfied, 4=satisfied, 3=neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 2=dissatisfied, 1=very dissatisfied). Overall, the questionnaire has a Cronbach's α=0.95, a value which confirms its reliability. In this study, the Cronbach's internal consistency index was measured and found to be sufficiently reliable, with a value of α=0.79. The ‘MJS’ questionnaire was translated into Greek using double translation (backward and forward translation). The questionnaires were distributed face-to-face.

Ethical considerations

In order to conduct the study, permission was obtained from the scientific and ethical committees of two hospitals. The participants were informed about the nature and the aim of the study, that their participation was voluntary and anonymous, and that they would need to sign the relevant consent form.

Data analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using the program Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 (SPSS, Inc. Chicago IL, USA). Continuous data were expressed as means (±standard deviation) and medians (interquartile range), while categorical and dichotomous variables were expressed as absolute values (n) and percentages (%) of the groups. The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality and normality plots were used to check the normal distribution of continuous variables. For the evaluation of personal satisfaction, workload, satisfaction from professional support, satisfaction from education in the workplace, salary, future prospects, as well as satisfaction from the prototypes of care offered, the one-way ANOVA was used. The significance level was set at α<0.05. Finally, Pearson's correlation index test was performed to find correlations between the subcategories of the questionnaire.

Results

Demographics

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. The majority of the participants were female (n=161, 91.47%), 25–34 years of age, 91 (49.43%) were married and had at least one child, 126 (71.6%) had technical nursing education and 16 (9.1%) university education. 32 (18.18%) had a Master of Science (MSc) and two (1.13%) had a doctoral diploma (PhD). Most nurses were working in the department of general paediatric pathology (44.32%). 11.36% of the nurses were working in the oncology unit, 14.77% in the surgical department, 15.91% in the intensive care unit and 13.64% in the intermediate emergency unit. Prior nursing experience was distributed as follows: 1–3 years 22.7%, 4–10 years 23.3%, 11–23 years 22.7% and 24–37 years 28.4%.

| Gender | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 161 (91.4) |

| Male | 15 (8.52) |

| Age (years old) | |

| <25 | 1 (0.56) |

| 25–34 | 69 (39.2) |

| 35–44 | 41 (23.8) |

| 45–54 | 53 (30.11) |

| >54 | 12 (6.25) |

| Family status | |

| Single | 80 (45.45) |

| Married | 87 (49.43) |

| Divorced | 9 (5.11) |

| They have one child | 91 (51.7) |

| They have no children | 85 (48.3) |

| Education Level | |

| Technological | 126 (71.6) |

| University | 16 (9.1) |

| Master degree, M.Sc | 32 (18.18) |

| Doctoral diploma, Ph.D | 2 (1.13) |

| Working department | |

| General | 78 (44.32) |

| Oncology | 20 (11.36) |

| Surgical | 26 (14.77) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit (nicu) | 28 (15.91) |

| Intensive care unit (ICU) | 24 (13.64) |

| Nursing experience (years) | |

| 1–3 | 40 (22.7) |

| 4–10 | 41 (23.3) |

| 11–23 | 40 (22.7) |

Nurses' satisfaction

Personal satisfaction (Table 2) was assessed as very satisfactory or satisfactory by 50.8% of the participants, whereas 15.5% reported dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. No effect of sex (p=.957), age (p=.538), family status (p=.352), educational level (p=.455) and the type of working unit (p=.62) was found. In the category of satisfaction from workload, only 33.3% of the participants reported being satisfied or very satisfied. Satisfaction from workload was not related to sex (p=.734), age (p=.435), the working unit (p=.205), the educational level (p=.259), the family status (p=.267) and prior nursing experience (p=.78). Regarding satisfaction from professional support in their workplace, 53.4% of the nurses reported being satisfied or very satisfied, while 14.7% were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. No relation was detected regarding satisfaction from professional support in the workplace and sex (p=.523), age (p=.790), working unit (p=.72), educational level, family status (p=.480) and prior nursing experience (p=.15).

| Category | Satisfied or very satisfied (%) | Dissatisfied or very dissatisfied (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Personal satisfaction | 50.8 | 15.5 |

| Satisfaction from the workload | 33.3 | 30 |

| Satisfaction from professional support | 53.4 | 14.7 |

| Satisfaction from in-work training | 24.7 | 44.8 |

| Salary satisfaction | 12.2 | 55.9 |

| Satisfaction from future perspectives | 26.4 | 31.7 |

| Satisfaction from care standards | 64.8 | 9.6 |

| Overall satisfaction | 45.4 | 16.4 |

One-way ANOVA was used to control for personal satisfaction, workload, satisfaction with professional support, satisfaction with in-service training, satisfaction with pay, satisfaction with future prospects, and satisfaction with standards of care. The existence of a statistically significant relationship between the subcategories of job satisfaction as presented in the MJS questionnaire and the independent variables, which were age, gender, marital status, education level, work department, and years of service, was investigated. Regarding workload satisfaction, no statistically significant difference was observed according to gender p=.734, age p=.435, work department p=.205, education level p=.259, marital status p=.267 and work experience p=.78.

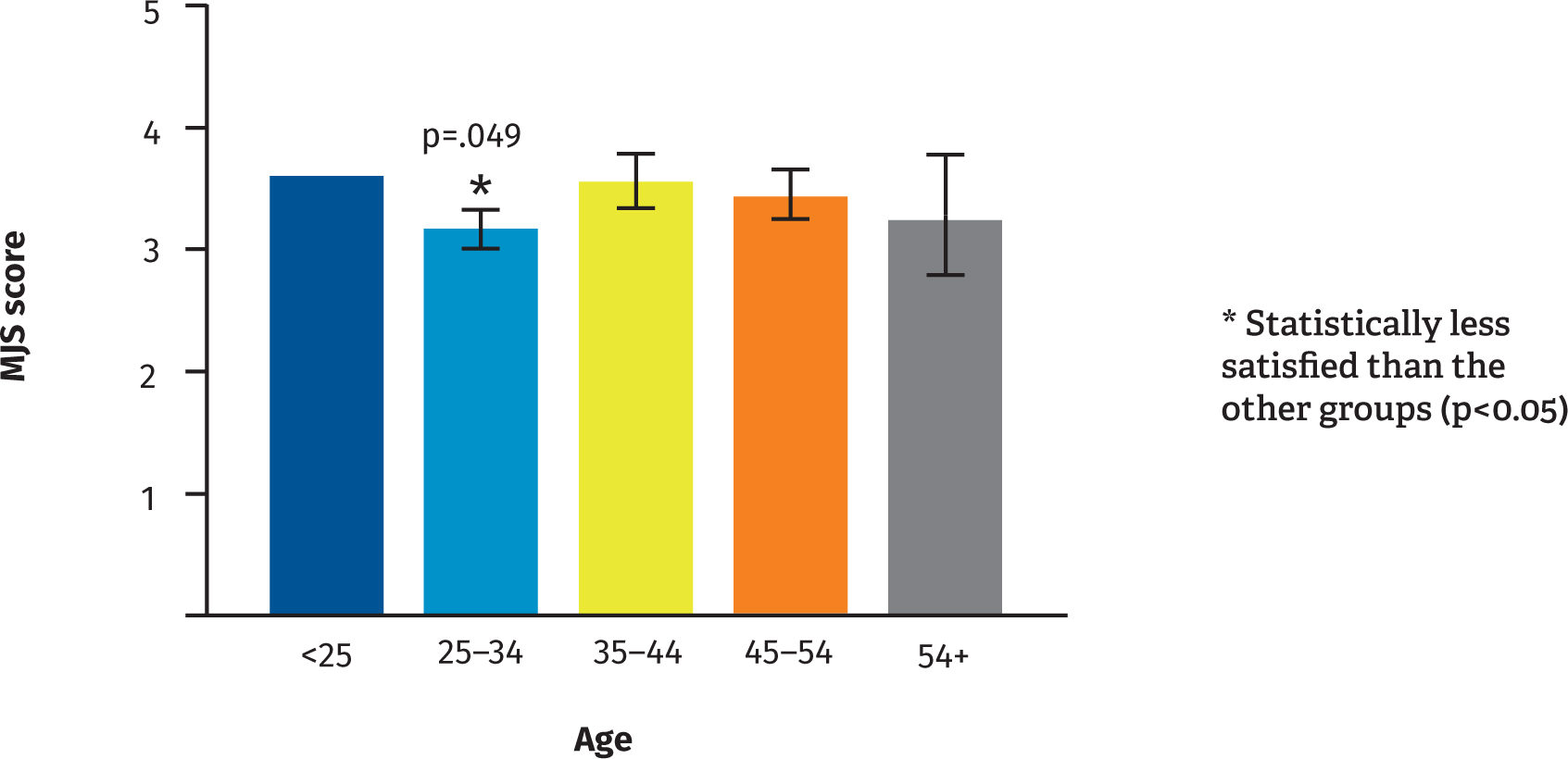

According to the analysis, there was a statistically significant difference in the age factor regarding nurses' satisfaction with in-service education (p=.049). As shown in Figure 1, nurses aged 25–34 years old were the least satisfied with in-service education (M=3.1681). This is followed by nurses aged over 54 years (M=3.2545), nurses aged 45–54 years (M=4.491) and nurses aged 35–44 years (M=3.5619).

Regarding nurses' personal satisfaction, analysis of variance showed no statistically significant differences in the factors of gender (p=.957), age (p=.538), marital status (p=.352), education level (p=.455) and work department (p=.62).

24.7% of the nurses were satisfied or very satisfied from the education received in their workplace, whereas 44.8% were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied.

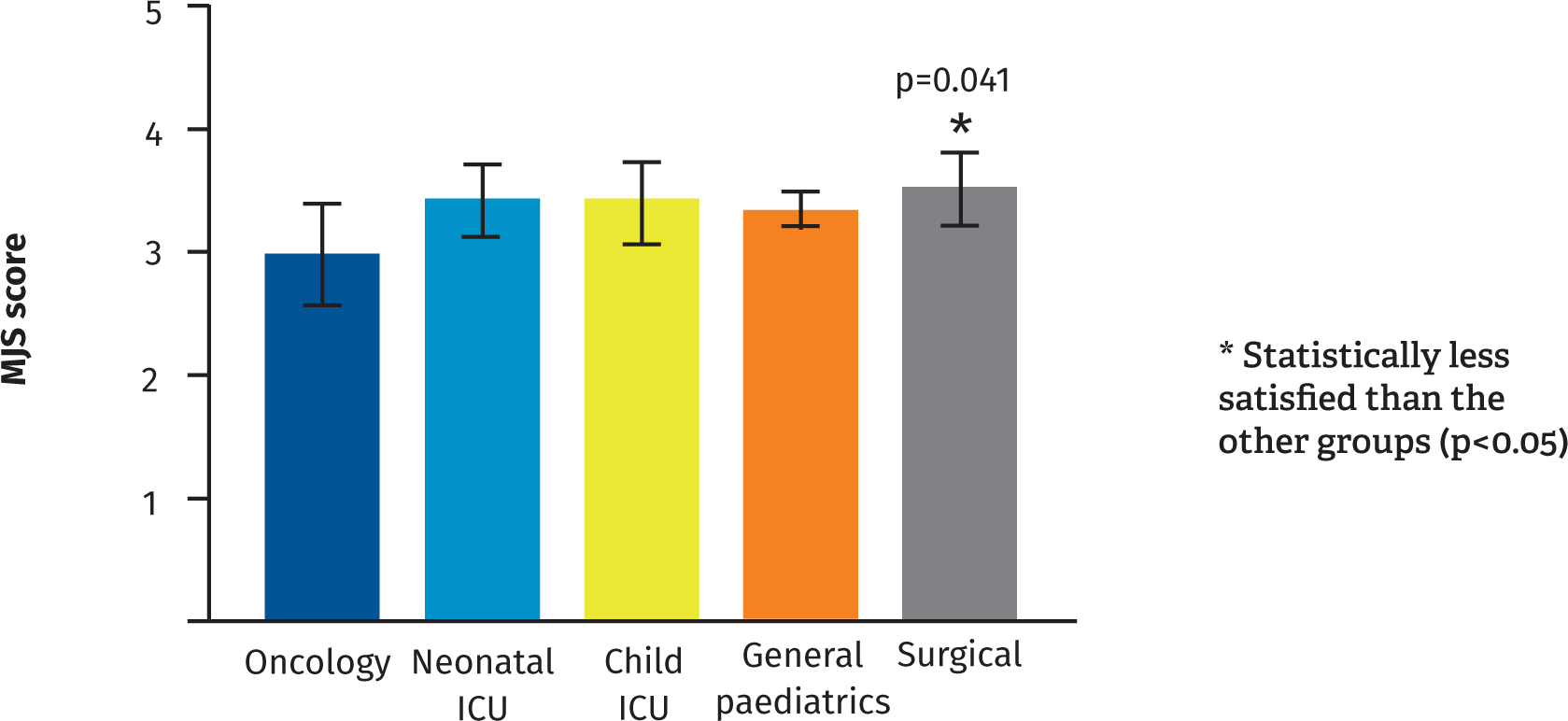

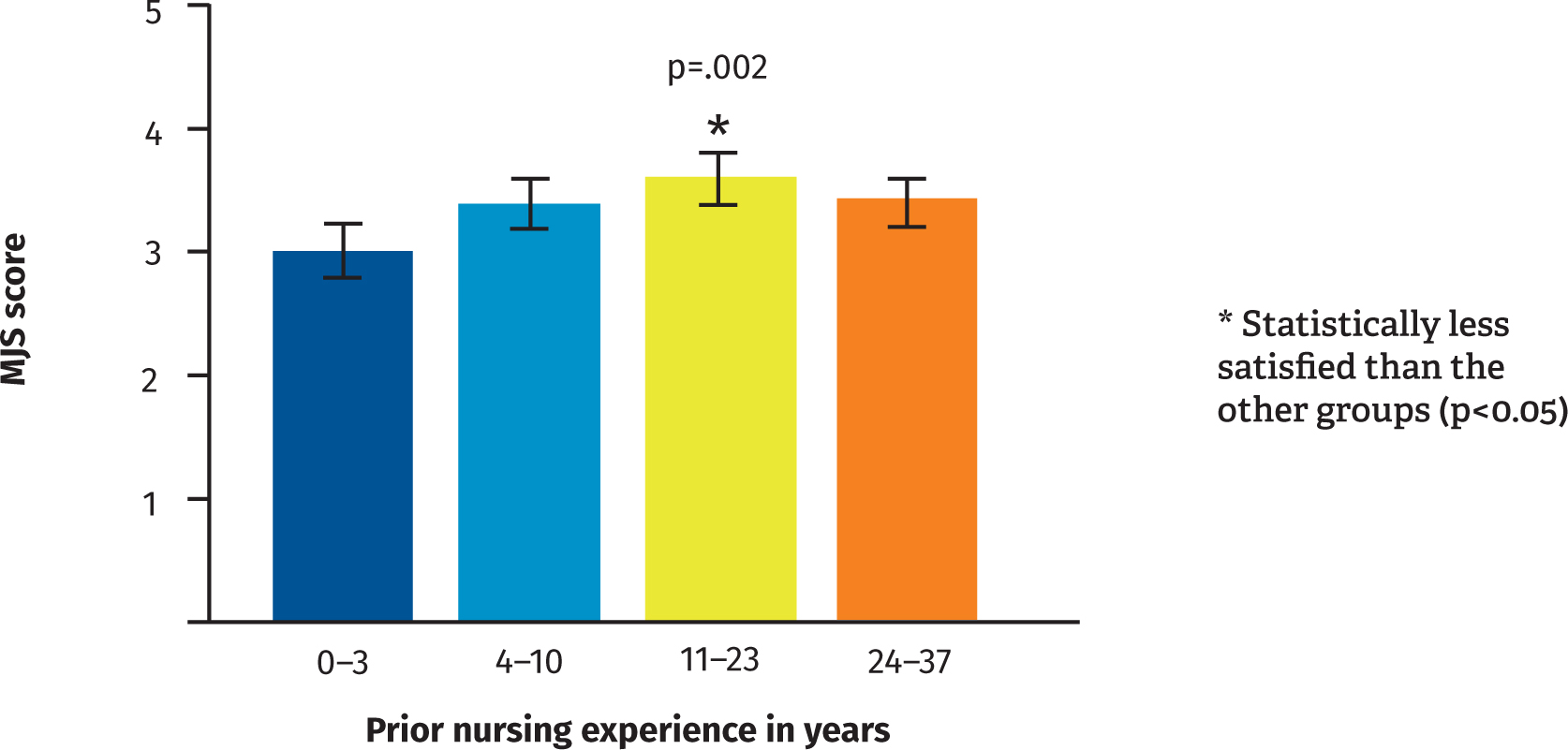

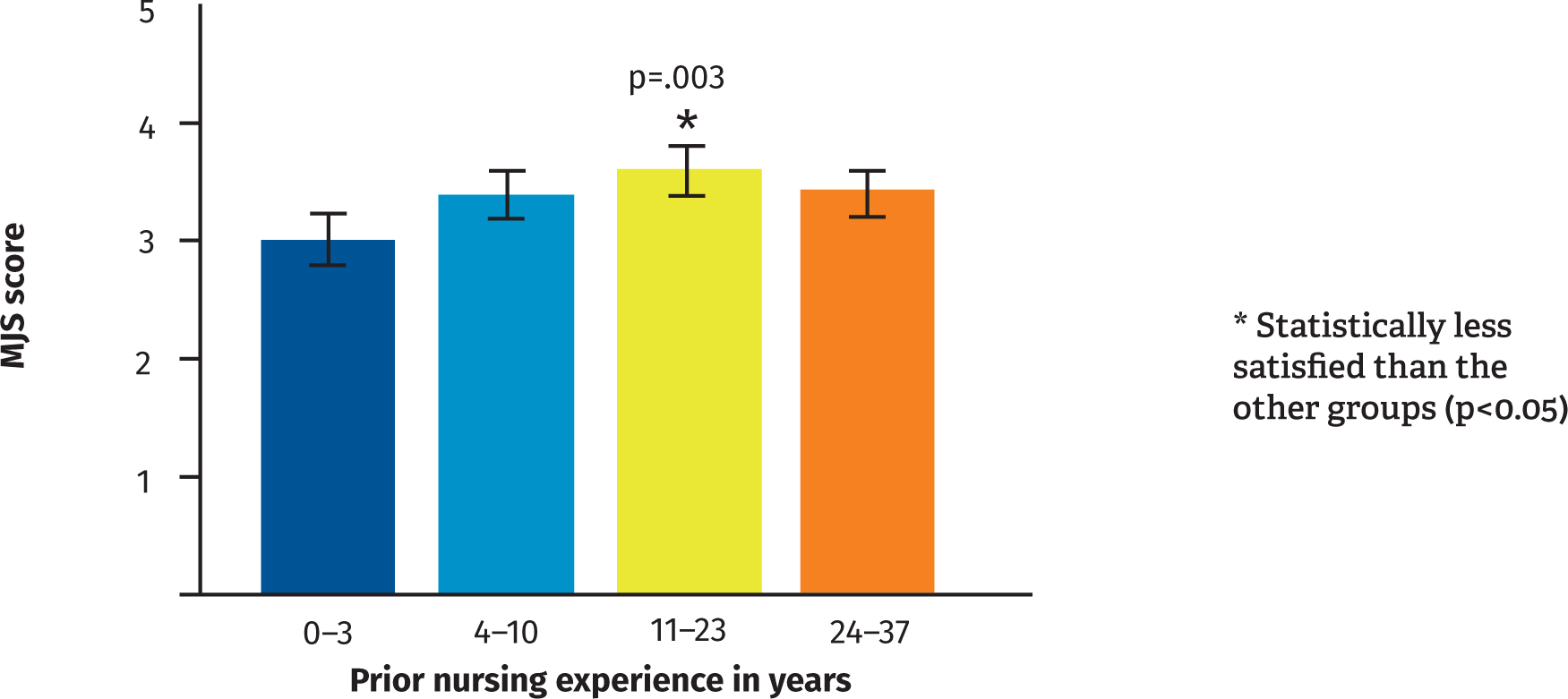

According to the analysis, there was a statistically significant difference in the age factor, regarding nurses' satisfaction with in-service training (p=.049). The least satisfied with in-service education were nurses aged 25–34 years (M=3.1681). This is followed by nurses aged over 54 years (M=3.2545), nurses aged 45–54 years (M=3.491) and nurses aged 35–44 years (M=3.5619) (Figure 1). Also, a statistically significant difference was observed in satisfaction with in-service training and nurses' workplace training (p=.041). Nurses in the surgical departments (M=3.5143) were more satisfied with their workplace training than nurses in the other departments. This is followed by nurses in the neonatal unit with M=3.4167, while nurses in the oncology departments appeared less satisfied with M=2.9857 (Figure 2). Prior experience also appeared to influence nurses' satisfaction with in-service education (p=.002). Nurses with previous nursing experience of 11–23 years were observed to be more satisfied with their training (p=3.6000) compared to other nurses (Figure 3). This was followed by nurses with 24–37 years of experience (M=3.4036) and finally nurses with 0–3 years of experience (M=3.0050). The following factors, gender (p=.631), education level (p=.947) and marital status (0.060) did not have a statistically significant effect on in-service training.

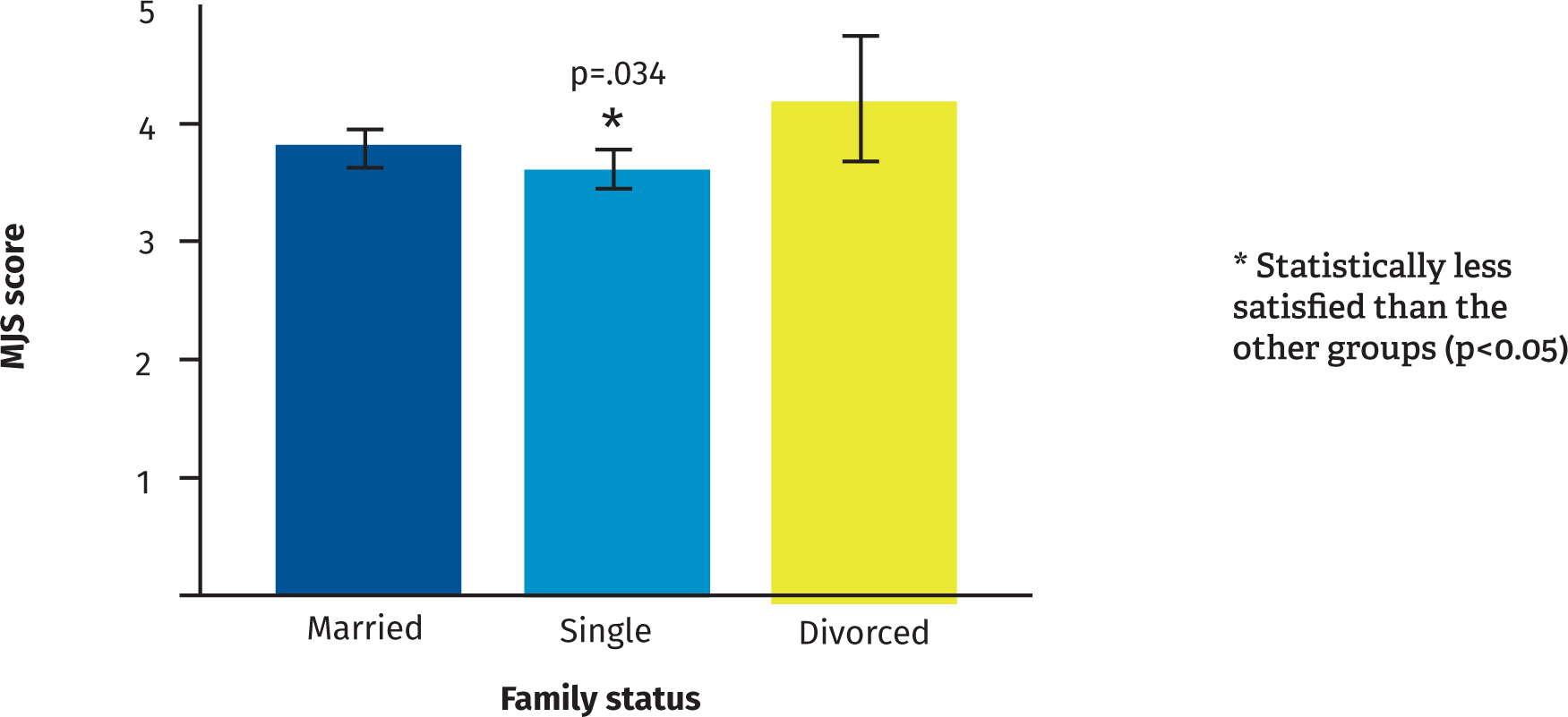

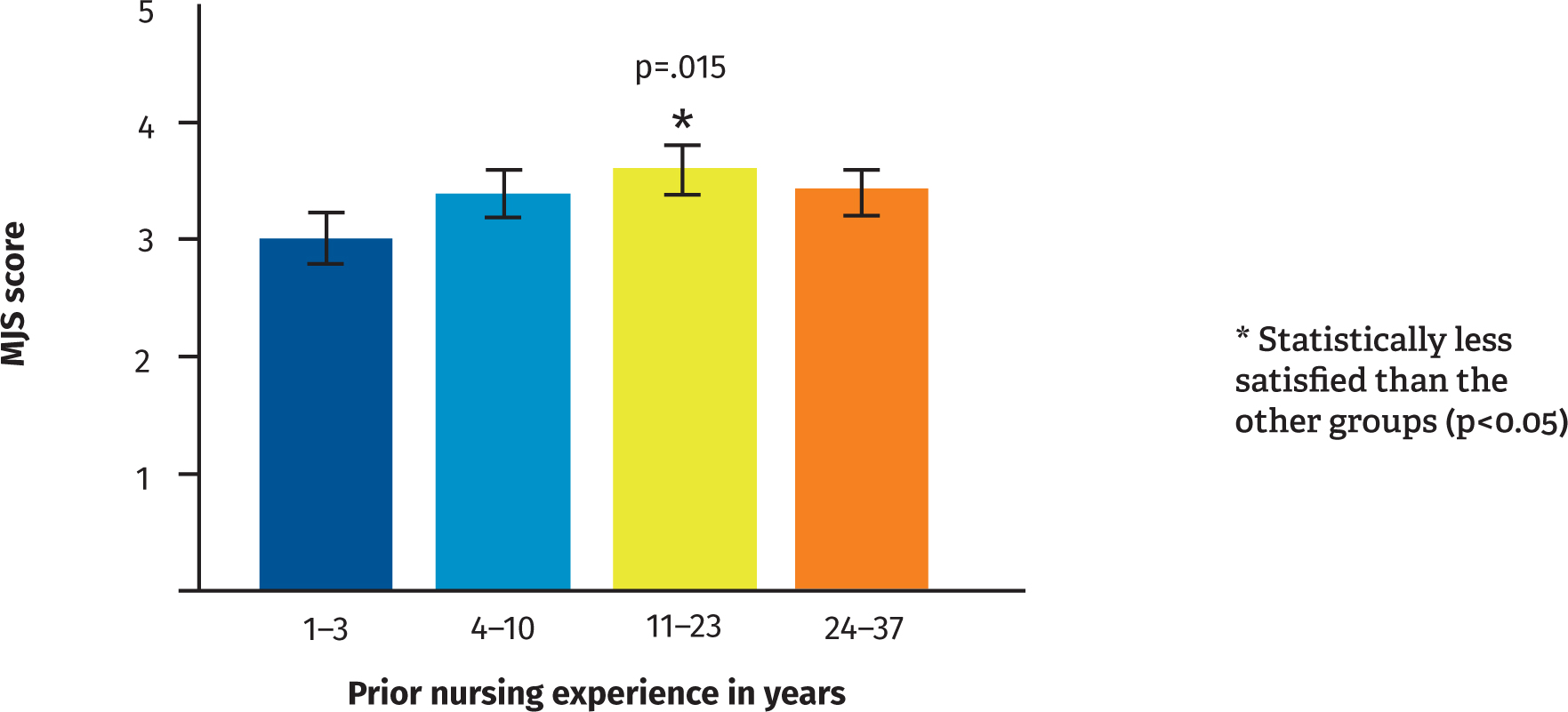

Only 12.2% of the participants were satisfied or very satisfied from their salary, while 55.9% stated that they were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. Satisfaction with pay appeared to be influenced by nurses' marital status (p=.034) and also by seniority (p=.003). As shown in Figure 4, unmarried nurses were the most dissatisfied with their pay (M=3.5063), while married (M=3.6695) and divorced (M=4.1944) nurses were observed to be the most satisfied. Nurses with 0–3 years of experience were more dissatisfied with their salary (M=3.1813) compared to other participating nurses. As years of service increased, nurses' satisfaction with financial rewards increased. Nurses with 24–37 years of service were most satisfied (M=3.7636) followed by nurses with 11–23 years of service (M=3.7563) and nurses with 4–10 years of service (M=3.7317). The other variables such as gender (p=.127), age (p=.106), work department (p=.716) and educational level (p=.283) did not seem to have a statistically significant effect on pay satisfaction (Figure 5). 26.4% of the participants were satisfied or very satisfied with future prospects, while 31.7% of them were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. Satisfaction with future prospects was analysed in relation to the independent variables gender (p=.419), age (p=.506), work department (p=.367), educational level (p=.905) and marital status (p=.524), without a statistically significant relationship. In contrast, seniority appeared to influence nurses' satisfaction with future prospects (p=.015). Figure 6 shows that nurses with 11–23 years of seniority were the most satisfied with future prospects compared to their other colleagues (M=3.3458). This was followed by nurses with 24–37 years of experience (M=3.1212), nurses with 4–10 years (M=3.0528) and finally nurses with 1–3 years of experience (M=2.8792) (Figure 6). Satisfaction from future prospects was not related to sex (p=.419), age (p=.506), type of working department (p=.369), educational level (p=.905) and family status. 64.8% of the participants reported they were satisfied with the prototypes of care offered to children and only 9.6% of them reported being dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. Regarding general satisfaction from their work, 45.5% of nurses participating in this study reported being satisfied or very satisfied and only 16.4% reported being dissatisfied or very dissatisfied (Table 2).

Discussion

In recent years, greater attention has been focused on the quality of health services and nursing care of paediatric patients. Job satisfaction and quality of life of paediatric nurses as important factors influencing and improving the experience of children during their hospitalisation has been the subject of research. The present study investigated the job satisfaction of nurses working in two public paediatric hospitals in Athens, Greece, and the factors that influence it. In addition, the quality of their professional life and the relationship between its different aspects, emotional satisfaction, burnout and secondary traumatic stress, were studied. The findings oshow that job satisfaction is influenced by only a few factors, and some interesting correlations emerged regarding the quality of professional life.

The responses of all respondents revealed that 45.4% of paediatric nurses were satisfied to very satisfied with their work, while 16.4% were dissatisfied to very dissatisfied. Analogous results were obtained in a similar survey where nurses were moderately satisfied with their job with M=2.7947. In the individual categories of job satisfaction, high percentages are obtained in personal satisfaction with the profession, support of nurses in the working environment and satisfaction with the standards of care provided to patients. In contrast, satisfaction with salary emerges as the category with the highest rate of nurses' dissatisfaction (55.9%). Similarly, in Papadamu's survey, the dimension ‘Pay and nature of work’ had the lowest mean across all respondents (M<2.04 in both hospitals) (Stamm, 2005). In the present study, it was observed that age factor influences nurses' satisfaction with on-the-job training. Individuals aged 25–34 years were more dissatisfied with their on-the-job training than nurses of older age groups. Nurses over 50 years of age appeared to be more satisfied with their job, whereas in contrast, in another study (Ferrens, 1990), age as a demographic factor did not affect satisfaction to a statistically significant degree.

Previous experience is another important factor that influences nurses' job satisfaction, which is supported by additional studies. In this study, the factor of seniority seems to have a statistically significant effect on paediatric nurses' satisfaction with their education, their satisfaction with (Ibrahim et al, 2016) remuneration and satisfaction regarding their future prospects. It was observed that nurses with 11–23 years of service were more satisfied with their education and future prospects, while nurses with 24–37 years of service were more satisfied with their salary. In contrast, nurses with the least years of experience, 0–3 years, reported the lowest levels of satisfaction regarding salary. The research by Ernst et al (2004) also demonstrates that seniority as a factor, influences nurses' satisfaction. Nurses with more years of experience were more confident, less anxious, and more satisfied with the recognition they had as professionals in their work department than their younger colleagues (Ernst et al, 2004).

The marital status of nurses in this study appeared to have a statistically significant effect on their satisfaction with salary. Unmarried nurses appeared to be dissatisfied with their salary, while divorced nurses had the highest mean satisfaction. This may be due to the increased demands of single nurses in terms of salary, as their financial situation probably does not allow them to start a family. Marital status also seems to have an effect on nurses' satisfaction in other studies. In the study by Ibrahim and colleagues, it was observed that married nurses had higher rates of job satisfaction than unmarried nurses (Ibrahim et al, 2016). Regarding nurses' quality of professional life, the present study revealed that nurses receive a high degree of emotional satisfaction from their work, with a higher mean of M=4.16 (high means across all questions). Nurses who are in an environment with family support reported better quality of life (QOL). Married nurses who lived with their families and had children reported better scores of the social QOL domain compared to others. In some studies, nurses reported equally satisfactory levels of quality of life (Ibrahim et al, 2016); whereas in most, nurses report frustration or a desire to leave the profession (Khosrojerdi et al, 2018).

The literature reports that nurses in paediatric departments have high rates of occupational fatigue (Ernst et al, 2004; Khodayarian et al, 2008; Robins et al, 2009; Rochefort et al, 2010; Davis et al, 2013; Berger et al, 2015).

In this study (Nowrouzi et al, 2016), moderate levels of occupational fatigue were observed across all responses. Nurses felt exhausted from their work and reported being overwhelmed due to workload (M=3.72 and M=3.45 respectively). The interaction with the patients' family, the paradoxical demands and stress experienced by parents may account for the burnout and unpleasant feelings of paediatric nurses.

In the study by Li et al (2014), it was reported that one fifth of paediatric nurses experienced symptoms of secondary traumatic stress after the first 3 months of employment in their work department. High levels of stress after traumatic events were observed in nurses working in NICUs in a similar study by Mosadeghrad and colleagues (Mosadeghrad et al, 2011). In the present study, moderate levels of secondary traumatic stress were observed in all responses. The nurses experienced anxiety about the patients they cared for and felt frustrated because of the nursing care they provided to paediatric patients. Dealing with children experiencing illness, pain and facing death on a daily basis, as well as the grief that nurses face but also experience, can magnify anxiety and further impact their quality of life. An important finding is the association between the variables of burnout and secondary traumatic stress experienced by nurses. It was found that secondary traumatic stress leads to an increase in burnout. In contrast, Sekol and Kim's (2014) study reported the existence of a statistically significant correlation between emotional satisfaction and burnout in terms of work department. No statistically significant correlation was observed with regard to nurses' secondary traumatic stress (Sekol and Kim, 2014).

Limitations

A key limitation is the fact that the present study was conducted in Greece 1 year after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is likely to have affected the general psychological state of the participants, with a related effect on job satisfaction and quality of life in general. And the sample was based on only two public paediatric hospitals in Attica. The survey did not include nurses working in other general children's hospitals nor in private hospitals and this may have led to a selection error due to differences (working conditions, financial situation) between the target population of the study and the final population represented in the sample. Also, despite the sufficient number of the sample, there were disproportions in the individual categories formed by the sample. The majority of the nurses were female, the majority of the participants had a technological education and only two nurses held a PhD. As a result of these, in some cases comparisons were made between smaller and larger groups of participants. For this reason, an attempt was made to create larger categories to simulate the number of groups to be compared. Finally, there were risks to participation in the study, a possible emotional reaction for those who had experienced burnout.

Conclusions

In the present study the job satisfaction of paediatric nurses with relatively high educational background, working in tertiary care units was evaluated. Almost half of the participants reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their work. Although satisfied, this percentage is still far away from the goal we aim for. Prototypes of care seemed to be related to nurses' highest satisfaction levels. Professional support in the workplace was ralso elated to nurses' satisfaction.

In general, the most important factors, which affected the various categories of professional satisfaction were age, type of working unit, previous nursing experience and family status, whereas gender and educational level had no effect on professional satisfaction in our setting. It appears that more support, improved conditions for education in the workplace, especially for individuals who are newcomers to nursing, as well as higher salaries and smaller workloads will most likely improve professional satisfaction, which is expected to favourably influence patient care and recovery. A rotation process for difficult units (like ICU and oncology units) may prove quite helpful.

Recommendations

A very important contribution to improving job satisfaction and other mental health symptoms is the design of an intervention plan by nursing leaders and other related groups taking into consideration the findings of various studies (Murray et al, 2016; Ghasemi et al, 2017; Lin et al, 2020; Soto-Rubio et al, 2020; Kagan et al, 2021; Khatatbeh et al, 2021; Monroe et al, 2021):