Childhood obesity is a longstanding national and international public health issue (Agha and Agha, 2017). Data from Public Health England's (PHE) National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) demonstrate the rapid increase in the prevalence of childhood obesity in England. The annual NCMP 2022–2023 results revealed 21.3% of reception children in England were identified to be overweight or living with childhood obesity and 36.6% in year 6 were overweight or living with obesity (The NHS Information Centre, 2023)

Existing research recognises that children living in poverty are at a greater risk of being above a healthy weight (Rautava et al, 2021). Research places an emphasis on the multi-causal nature of obesity (Barry et al, 2009) some of which are environmental factors. For example, existing research recognises that children living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods are at a greater risk of being above a healthy weight (Rautava et al, 2021). In addition to environmental factors, sedentary behaviours, lack of sleep and increased screentime have all be found to be highly correlated with childhood obesity (Albataineh et al, 2019; Han et al, 2020).

Most current childhood obesity interventions focus on changing younger children's (aged 6–12) weight through diet, increasing exercise and reducing sedentary behaviour (Malden et al, 2020). Although some childhood obesity interventions incorporate some parenting elements in their prevention programmes, there are few childhood obesity interventions that focus exclusively on parental feeding styles. However, there is a growing body of literature that recognises the importance of focusing on parental feeding styles during parenting intervention programmes to modify parental feeding and child eating behaviour (Russell and Russell, 2018; Wood et al, 2018). Parents are regarded as the main health promoter, educator and role model in the child's social life, and can have a major influence on their eating habits and lifestyle choices (Christian et al, 2013; Draxten et al, 2014). Parents play a key role in the development, influence and maintenance of children's eating beliefs, attitudes and habits through parental feeding behaviours (Gicevic et al, 2016). Thus, the adoption of some parental feeding behaviours may lead to some unhealthy eating habits in children (Demir and Bektas, 2017).

The service offers an intervention working solely with parents to address parental feeding behaviours, which are the parental behaviours which are informed by beliefs and attitudes around food and feeding and defined parental interactions with their child during mealtimes (Wardle et al, 2002). Parental feeding behaviours make an important contribution to children's eating behaviours and weight status (Liew et al, 2020). There are four established parental feeding practices in the research literature (Wardle et al, 2002):

Several studies have demonstrated that encouragement and control over children's eating are correlated with lower consumption of sugary drinks, and higher consumption of water and fruit and vegetable intake (Brown et al, 2008; Lo et al, 2015). In addition, research by Rodenburg et al (2013) demonstrated that emotional and instrumental feeding parental styles are associated with increased frequency of children's snacking.

The service developed an innovative 6-week parent intervention designed to address parent feeding practices in group or individual sessions. The parent intervention is available to parents and carers of children who are above a healthy weight are aged 5–17 years, and who live, attend school or are registered with a GP in either of the commissioned boroughs. The intervention incorporates elements of cognitive behaviour therapy, systemic theory and health coaching and focuses on a range of topics related to healthy living from a psychological perspective. The present service evaluation focuses on the four parenting feeding practices outlined above.

Internal monitoring and reporting of the intervention have previously indicated good outcomes. The intervention promotes two healthy parental feeding styles: parental control over eating and encouragement, and brings to parents' attention the less helpful parental feeding styles: emotional feeding and instrumental feeding. The aim of the intervention is to decrease parental emotional feeding and instrumental feeding and to promote the two healthy parental feeding styles parental control over eating and encouragement.

The main aim of the paper was to evaluate if the parent intervention is effective in changing parent feeding practices among parents of children living with obesity. This paper also examines if there was a difference in parental feeding style outcomes due to mode of delivery, individual or group intervention. Using secondary analysis of historical data, this service evaluation set out to test the following hypotheses:

Methods

This paper is written up following the revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellences (SQUIRE 2.0) guidelines (Ogrinc et al, 2016).

Context

It is beyond the scope of this service evaluation to examine children's BMI as the service is not commissioned to record measurement of weight therefore pre- and post-BMI are not included in the service's outcome measures. The service was established in 2017 as a commissioned pilot project in response to the increasingly complex cases related to healthy living (e.g. mental health difficulties with children and parents, social economic concerns and safeguarding) presenting in the existing community-based secondary care services (also known as tier 2 services). Over 6 years, the service trialled and developed different models of the intervention, which finally led to the parent intervention based on learning from previous models. The first model of the service delivered in 2017, focused on individual cases and involved direct work with children, young people and families. There was no parent programme yet. The first model reached capacity (50 cases) within the first 6 months due to the high number of case management tasks needed for the presenting complexity. One of the learning points from the first model of the service was that there were better outcomes when working with the parents of children and young people compared to working with the children and young people on their own. This led to the development of the current parent intervention (model 3), which commenced in September 2020.

The parent intervention was initially delivered face-to-face; however, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was adapted for virtual delivery via a video conferencing platform and over the telephone. Interestingly, virtual delivery increased engagement and attendance more than with face-to-face delivery. After the pandemic due to better online engagement, the intervention continues to be predominately delivered online. However, parents who request face-to-face sessions are accommodated. Referrals for the current parent intervention mainly came from the community childhood obesity multidisciplinary team, which the service coordinates, and includes a paediatrician, nutritionists and family support workers. Other professional referrals were from the school nursing team, or GP service as well as self-referrals.

Design

A repeated measures design, with 6 weeks between measures was used to compare scores on the four Parental Feeding Style Questionnaire (PFQ) sub-scales. An independent group design, with mode of delivery (group versus individual sessions) as the independent variable and PFQ sub-scales as the dependent variables, was used to test for differences in sub-scales due to mode of delivery.

Measures

Wardle et al (2002) developed the PFQ which has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of parents' feeding behaviours in the general population (Tam et al, 2014). PFQ scores are routinely collected by the service where the intervention was delivered. The 27-item PFQ is designed to measure the following four sub scales:

The five-point responses to all the items are: ‘never’ scoring one point; ‘rarely’ (two points), ‘sometimes’ (three points); ‘often’ (four points), and ‘always’ (five points). The four scales are scored by finding the means of each scale (i.e. the total score of the subscale divided by the number of questions in the subscale). A higher mean score on each scale indicates a higher parent disposition to adopt that feeding style.

Description of the intervention

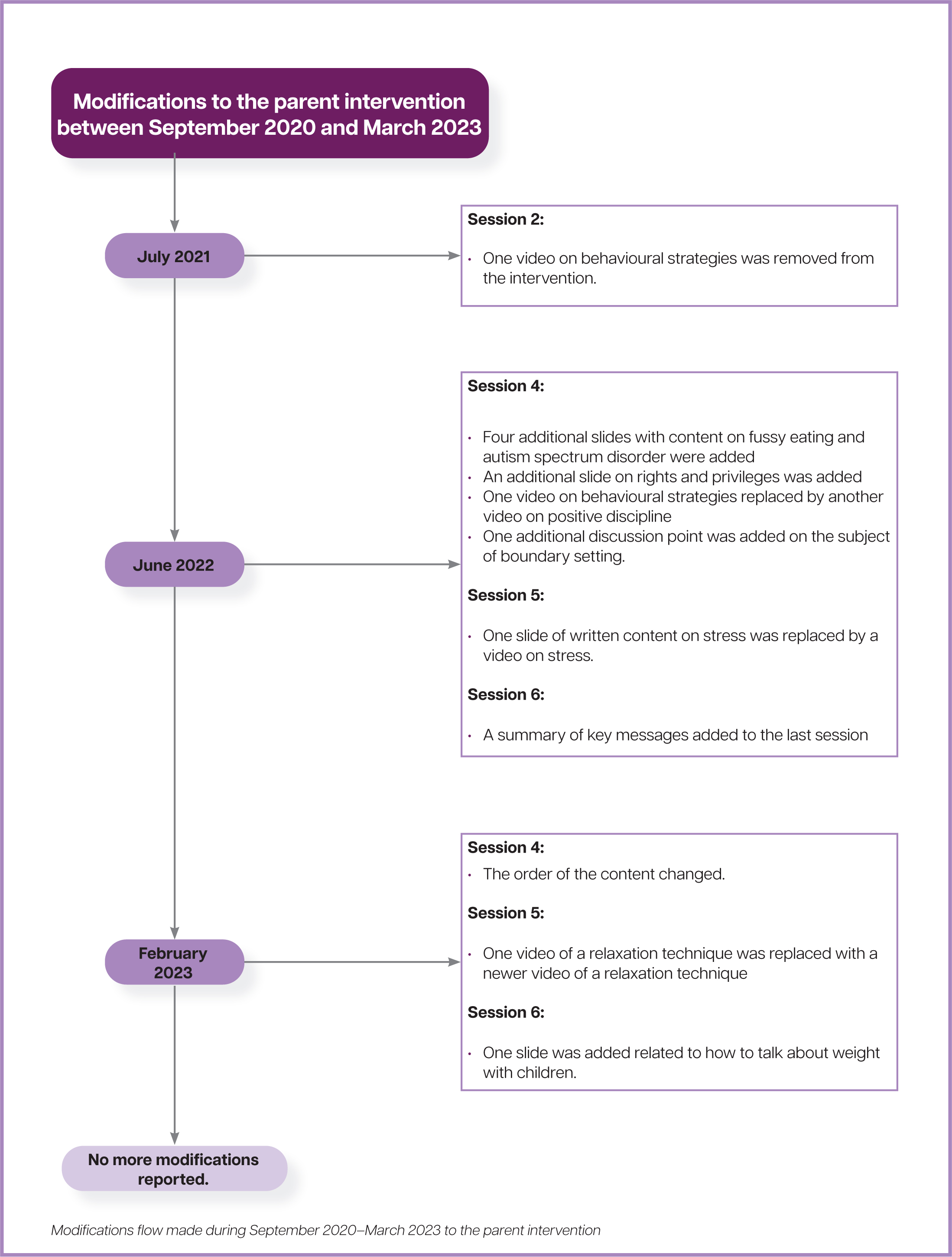

The intervention was initially designed to be delivered face-to-face. However, due to the pandemic it was adapted to be delivered online. Modifications made to the parent intervention during the course of model 3 delivery can be found in Figure 1. The majority of the data for this research are from the delivery of the group intervention which was delivered online only. The remainder of the data is from individual sessions that were online, over the telephone or face-to-face. The intervention is described using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TiDier) framework (Hoffmann et al, 2014) and can be found in Table 1.

| Item | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| BRIEF NAME | The intervention | |

| 1 | WHY |

The aim of the parent intervention is to support families to live healthier lives both physically and emotionally. The focus is on encouraging parents/carers to encourage their children to have a healthy relationship with physical activity and food. |

| 2 | WHAT: |

PowerPoint slides are presented during each session. Parents are emailed a copy of the slides after the end of the session. PowerPoint slides include: information, discussions, activities, videos and a home-task to implement the following week. |

| 3 | PROCEDURES: |

Parents are referred to the parent intervention through multiple routes, including self-referrals in response to promotional activities (e.g, posters, leaflets and the service's webinars; professional referrals in response to monthly childhood multidisciplinary team meetings. |

| 4 | WHO PROVIDED |

The parent intervention was developed and designed by a clinical psychologist and a counselling psychologist in the service. Operationally led by the service clinical psychologist. |

| 5 | HOW |

The group parent intervention was designed to be either delivered as a group or an individual intervention. It was initially delivered face-to-face but was adapted to be delivered online using a video conference platform due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The online intervention had a better attendance rate and the intervention continues to be mostly delivered online. |

| 6 | WHERE |

Sessions are delivered using a video conference platform. Parents who do not have access to technology are offered individual sessions over the telephone or face-to-face at the service's location. |

| 7 | WHEN and HOW MUCH |

Each session lasts for 1.5 hours and runs once a week, for 6 weeks, in the morning (usually 10.00–11.30am) during term-time only. |

| 8 | TAILORING |

During the pre-intervention assessment, a psychological formulation helps to inform which parts of the intervention to focus on (e.g. fussy eating or neurodevelopmental diagnosis). |

| 9 | MODIFICATIONS |

Please see the timeline in the Methods section for the intervention modifications that took place during the data collection period between September 2020 and March 2023. |

At time point 1, parents attended an individual assessment meeting and completed the time 1 (pre) PFQ. Parents then attended 6-weekly individual or group 60–90 minutes sessions with facilitators. The facilitators were a clinical psychologist, counselling psychologist, assistant psychologist and a trainee health psychologist. These sessions were held either via video call, telephone or face-to-face. The sessions focused on a variety of topics relating to the emotional and physical health of children, including parenting styles and feeding practices. After each session, parents were given weekly home tasks to complete. Once the parent had completed the parent intervention or at least 50% of the intervention, the parent completed the time point 2 (post) PFQ.

The inclusion criteria consisted of parents and carers of 5–17-year-olds who lived in, attended school or who were registered with a GP in the two commissioned boroughs for the parent intervention, and whose weight fell within the overweight or obese range according to BMI measurements of >25. Some referrals also came in as a result of the National Child Measurement Programme (GOV.UK, 2023). In addition, parents must have completed at least 50% of the invention to complete the post PFQ, for their data to be included in the data analysis. Eligible participants who meet the inclusion criteria were contacted by the service to arrange an assessment meeting before commencing the parent intervention.

Data for the service evaluation were collected by the service for monitoring, service development and reporting purposes. This paper uses historical data to analyse and report on pre- and post parent interventions since its implementation (as described previously) from September 2020. The data therefore comprises pre-and post data that were collected from parents who attended the 6-week parent intervention between September 2020 and March 2023, when the final data were collected.

Data analysis

The researcher received the scored anonymised data for each of the pre-and post variables in a password-protected document. Data were entered and analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 28.0.1.1 (14). There were no missing data. First, descriptive statistics were used to summarise the sample characteristics. Second, paired sample t-tests were used to compare the four sub-scale scores on PFQ at pre- and post-test. Thirdly, an independent samples t-test was used to compare PFQ score differences between group and individual sessions.

Seventy-five parents/carers of children aged 5 to 17 years of age who met the inclusion criteria were included in the service evaluation to assess the relationship between the pre-and post-variables. All parents provided responses at both pre-and post-test. Due to being a secondary analysis, we could not establish power a priori. A posteriori analysis was conducted using G*Power version 3.1.9.6 for sample size estimation, based on data from Cohen's (1988) general guidelines for detecting a ‘small’, ‘medium’, or ‘large’ effect size. Using Cohen's (1988) criteria, the effect size 0.5 was a medium effect size. With a significance criterion of а=.05 and power=.80, the minimum sample size needed with this effect size was n=45 for differences between two dependent means. Thus, the obtained sample size of n=75 is adequate.

Ethical considerations

The service sought consultation with their data protection officer around using historical data for research purposes. The data protection officer assessed the risk and approval for the research to be conducted has been permitted by the service provider's data protection officer. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Staffordshire in March 2023.

Findings

Descriptive statistics were used to check for missing cases and to confirm that the minimum and maximum values for each score for the PFQ variables were within range. Although outliers were identified, cases were not excluded as an inspection of the 5% trimmed mean revealed that the trimmed mean values were identical to the mean values, indicating the distribution was not skewed (Pallant, 2020). Sixty-eight per cent of parents/carers completed the group intervention and pre-and post PFQ, while 32% completed the individual sessions and pre- and post-PFQ. An overview of the participants social demographics at baseline can be found in Table 2.

| Baseline characteristics | Full sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Family members who attended the intervention | Mother | 71 | 94.7 |

| Both parents | 2 | 2.7 | |

| Grandmother | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Mother and older sibling | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Sex | Male | 46 | 61.3 |

| Female | 29 | 38.7 | |

| Child ethnicity | White | 25 | 33.3 |

| Black | 17 | 22.7 | |

| Asian | 6 | 8 | |

| Other | 13 | 17.3 | |

| Unknown | 14 | 18.7 | |

| Type of session | Group | 51 | 68 |

| Individual | 24 | 32 | |

To examine the effectiveness of the intervention, paired sample t-tests were computed to compare the pre-and post PFQ sub-scales. The effect size was calculated using Cohen's d (Table 3). Effect size is a measure of the magnitude of the intervention's effect and is independent of the sample size (Carter, 2019). The established criteria to interpret the strength of the effect sizes are as follows: small (d=0. 2), medium (d=0. 5) and large (d=0. 8) (Cohen, 1988). The larger the effect size the stronger the relationship between pre-and post intervention scores (Lakens, 2013).

| Measure | Pre | Post | 95% CI | t | p | Cohen's d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||||

| Instrumental feeding | 1.8 | .64 | 1.57 | .63 | .11 | .57 | 2.93 | .004 | .36 |

| Control over eating | 3.61 | .65 | 3.72 | .66 | -.45 | .01 | -1.95 | .055 | .18 |

| Emotional feeding | 1.71 | .76 | 1.41 | .52 | .24 | .72 | 4.17 | <.001 | .46 |

| Encouragement | 3.83 | .71 | 4.05 | .67 | -.57 | -.10 | -2.92 | <.001 | .33 |

There was a statistically significant decrease in Instrumental Feeding scores; t(74)=2.93, p=.004. Cohen's d=0.36. The Cohen's d effect size indicates a small effect. Results suggest that parents reported lower rates of instrumentally feeding their child after attending the parent intervention. There was a statistically significant decrease in the scores for Emotional Feeding t(74)=4.17, p < .001. Cohen's d=0.47. The Cohen's d effect size indicates a small effect size. Results suggest that parents reported reduced rates of emotionally feeding their child after attending the 6-week parent intervention.

There was a statistically significant increase in the scores for Encouragement t(74)= 2.92, p=.005. Cohen's d=0.33. The Cohen's d effect size indicates a small effect size. These results suggest that parents reported increased encouragement for their child to eat healthily after attending the six-week intervention.

No statistically significant differences were found in between scores for Control over eating t(74)=1.95, p=.06. Cohen's d=0.18. The results found that control over eating was found to have no significant effect for parents who attended the intervention. Although the means for control over eating showed an increase, it was not significant.

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the differences between group sessions versus individual sessions. No significant differences were found at pre-intervention or post-intervention, indicating that both modes of delivery are equally effective.

Discussion

The present paper aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the service's parent intervention at improving feeding behaviours of parents of children living with obesity. Parents who received the intervention reported significant positive changes on three of the four PFQ sub-scales: Parental Encouragement, Emotional Feeding and Instrumental Feeding. The individual mode of delivery showed equally positive outcomes as the group mode of delivery.

Our results indicate that the parent intervention is a beneficial parent-based intervention for children living with overweight or obesity. Furthermore, the service evaluation strengthens the idea for psychoeducation on parental feeding styles to be included in family-based children's weight management interventions as a therapeutic component for parents/carers, aimed at improving children's eating behaviours and lifestyle choices (Matheson et al, 2015).

Results show that the parent intervention had a small effect on parents/carers encouraging their children to eat healthily. This result is promising as it supports evidence from previous research studies, which show that parental encouragement to eat healthily has positively corresponded with healthier children's eating behaviours (Lo et al, 2015). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, parental encouragement to eat healthily was demonstrated as the most effective parental feeding style to promote children's healthy weight status regardless of psychological, social or economic conditions (Davodi and Ahadi, 2021). The results from the current service evaluation corroborate the ideas of Davodi and Ahadi (2021), as the majority of the data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic when there was high uncertainty and anxiety over the duration of social distance restrictions, lockdowns, online schooling and working from home; it is, therefore, a particularly valuable finding.

We also found that parental instrumental feeding significantly decreased after attending the intervention. This finding is reassuring as, previous research found parental instrumental feeding to be a potential parental risk behaviour for children's overeating at times when there was not a physiological need, as the child may have learnt eating cues other than physical hunger (Raaijmakers et al, 2014). This parental feeding style has been found to increase children's consumption of unhealthy snacking (Wang et al, 2017) and increase the child's weight status over time (Beckers et al, 2021; Hamaker et al, 2015; Rodenburg et al, 2013). Parental instrumental feeding has also been associated with a decrease in children's water intake and an increase in sugary beverage consumption, as well as a decrease in children's fruit and vegetable consumption (Inhulsen et al, 2017).

The parent intervention was also found to significantly decrease parental emotional feeding. Emotional feeding has been identified as another potential parental risk behaviour (Raaijmakers et al, 2014). Previous studies have found evidence that children eventually learn to regulate their emotions through food when repeatedly exposed to a parent that is an emotional feeder (Braden et al, 2014). This is harmful as, children learn to ignore the physical hunger cues and cues when they are full, which may contribute to overeating (Farrow et al, 2015). The parent intervention was found to have a small to approaching medium effect size on parental emotional eating. It is therefore a particularly important finding as it suggests that parents were able to understand the key messages on emotional feeding in the intervention and were able to apply the practical skill-based guidance to change their feeding behaviour when responding to their child's emotional needs.

An unexpected finding was that the parent intervention did not to have a significant impact on parental control over eating. These findings are somewhat surprising given that there was evidence of an increase in post-test control scores, however, not a significant one. This suggests that the intervention might need refining to lead to larger effects on this variable. At the time of writing, a full review of all materials including an internal data analysis evaluation has taken place to ensure that the key takeaway messages, including those relating to parental control over eating, from the intervention are explicit and relevant to the current living environment.

The possible interference of the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be ruled out when considering the finding regarding parental control over eating, as the majority of the data were collected during both the first and second wave of the pandemic and may be a possible reason why parental control over eating was not significant. This was a time where family routines and freedoms were abruptly disrupted due to the government social distance restrictions. Due to the disruption in education, working and routines, this may have led to a broader sense of decreased control over lifestyle, food choices and activities in general (Aymerich-Franch, 2023). These issues could have been further exacerbated for families who were facing financial pressure and the loss of free school meals during that time (Davison et al, 2021; Khan, 2022). To develop a full picture of parental control, future research conducted under service-level conditions could consider a comparison of the current results with post COVID-19 data collection of the pre-and post-intervention scores, to investigate if the pandemic affected parental control over eating.

Another important finding of the parent-based intervention is that both modes of delivery, group or individual sessions, were found to be as effective as each other. These findings give assurances that the parent intervention is effective in terms of its reach, accessibility and outcomes. One benefit of the group intervention is that it is more cost-effective. The reach of working with parents is broader compared to individual sessions, which helps to meet the demands of the service and keep waiting lists to a minimum. However, the service offers the parent intervention on an individual basis to ensure accessibility to the intervention. Due to group sessions being more economical, the service offered this to parents in the first instance. However, if there were parental barriers to attending the group such as a language barrier or no access to necessary technology, then they were offered individual sessions either, face-to-face, virtually or over the phone.

It should be noted that 68% of parents completed the group sessions while 32% of parents completed individual sessions. It is standard protocol for parents to be placed in the group intervention on referral, unless there is a reason why the parent cannot access to the group (for example, an interpreter required). In that instance, individual sessions were offered. However, it could also be possible that group sessions proved more popular for parents who were looking for the social benefits and support of other parents with similar experiences, especially during the hight of the COVID pandemic (Pappas, 2023). Further research would be useful to explore this area in more depth.

There were several strengths and limitations of this study which should be noted. Although the service evaluation uses a reliable and valid questionnaire (Tam et al, 2014), one limitation that cannot be overlooked is that these are self-report questionnaires. Due to their accessibility and convenience of when and where to complete questionnaires, self-reported questionnaires are a commonly used measure in internet-delivered interventions (Crutzen and Göritz, 2010). However, using any self-report questionnaire may lead to the potential issue of parental social desirability bias and recall bias where parents may provide responses that they believe consistent with the social norms and expectations of the parent intervention, misconstruing their self-reports in a favourable direction (Giménez Garcia-Conde et al, 2020). To develop a full picture of parental feeding styles, future research could include a combination of parental report and observational measures. In addition, the service evaluation did not include a control group. The parent intervention is commissioned on a yearly basis, making it a challenge due to inadequate time to recruit participants for a non-control group. It is therefore not known what changes to the parental feeding styles may have occurred without the parent intervention for comparison of the two groups. Although these are useful findings within their own right to inform and develop the service further, future research investigations with a waiting list as a control group is suggested.

The Service Evaluation will be used to inform the service's future direction and to continue to develop the service provision. In addition, the findings should make an important contribution to the field of childhood obesity interventions, where more evidence for best practice is needed to help inform commissioning decisions.

Conclusions

The parent intervention is aimed at promoting healthy lifestyle behaviours for children and young people who were overweight or living with obesity by supporting parents to change their feeding style. As far as can be ascertained, the findings of this research are novel and unique. Current findings suggest that the parent intervention has successfully adapted the originally designed face-to-face intervention to be delivered virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic for parents living in two boroughs. The findings demonstrate that it is a beneficial online health behaviour change intervention, which can change parents' feeding practices. The findings add to the existing body of research literature on the usefulness of virtual health interventions. However, further investigations are needed to confirm and validate these findings.