Everyday in schools students complain of headaches, stomachaches, nausea and fatigue. Many staff members, including school nurses, may dismiss these complaints as unfounded and nuisance visits, as these are symptoms that cannot necessarily be proven. However, Maughan (2018) found that approximately one third of all visits to the health office are related to mental health issues. These symptoms may be physical manifestations of mental and psychological issues which the student may not understand (Maughan, 2018). When these visits are dismissed as ‘frequent flyers’ or ‘attention seekers’ a larger problem may be masked leading to potential crisis and diminished academic achievement (Frauenholtz et al, 2017). When a student is not in class opportunities for learning are missed, creating a potential for negative impact on academic performance (Maughan, 2018). However, when problems are recognised by school staff, there is an increased chance of referral and treatment. Green et al (2016) found having a mental health referral within the school setting substantially improved absenteeism, which in turn had a positive effect on academic performance.

Mental health prevalence in adolescents

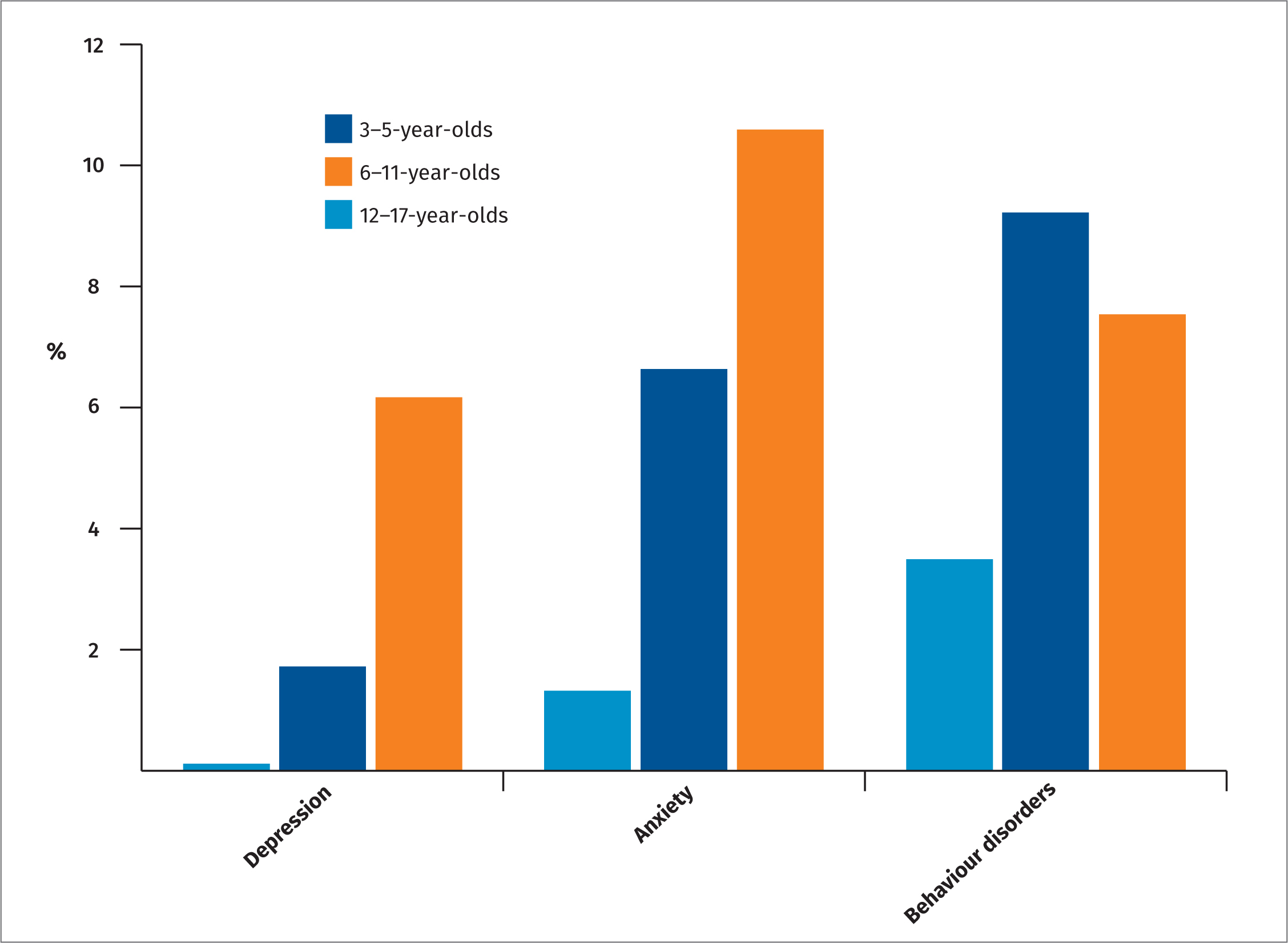

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020) in the United States, 9.4% of children aged 2–17 years have been diagnosed with ADHD. Among children aged 3–17 years, 7.4% have been diagnosed with a behaviour disorder, 7.1% have been diagnosed with anxiety and 3.2% have been diagnosed with depression (CDC, 2020) (see Figure 1). While these numbers are substantial, they do not account for the unknown number of children living with other mental and emotional disorders. While some students may be seen as ‘acting out’, others are suffering more silently, withdrawing in the classroom, visiting the nursing office, or skipping class or school.

Figure 1. Depression, anxiety and behaviour disorders in the United States.

Figure 1. Depression, anxiety and behaviour disorders in the United States.

While some experts minimise the role of stigma, the fear of it may prevent students from seeking help, or parents taking their children for diagnosis and treatment (Frauenholtz et al, 2017). This may be due to the differing perceptions and misconceptions of school staff members surrounding different mental health diagnoses. As a result, children and young people may face adverse repercussions related to unfair assumptions around their diagnoses (Frauenholtz et al, 2017). Delays in diagnosis leads to prolonged suffering, and as a result pupils are affected academically.

Role of staff members

In 2018, the National Association of School Nurses (NASN) took the position that school nurses play a vital role in the school mental health team in terms of aiding with stigma, lapses in care, and overcoming barriers, as they can be a vital part of identifying and managing mental distress. However, there is still a gap. It is important to make teachers part of the mental health team, not to diagnose or treat, but to recognise students in trouble and bring it to the attention of appropriate members of staff. However, many staff members feel uncomfortable to make referrals due to lack of training or misconception, leading to continued student suffering.

Methods

Between October 2019 and March 2020, a search of the literature was performed using the terms:

- School health services

- Mental health services

- Academics

- Mental disorders

- Teacher education and/or in-service

- Teacher perception

- Teacher attitudes

- Mental health

- Mental health literacy.

The following databases were used: CINAHL, ERIC, Academic Premier, PsychoINFO, PubMed, Google Scholar, as well as reference list searches. Approximately 101 196 articles were found after duplicates were removed. The following exclusion criteria were applied:

- Not being in English

- Published before 2014

- Not peer-reviewed

- Incomplete studies

- Did not meet the search criteria.

Ten studies were analysed that discuss the need for staff training, and the training methods currently being utilised (Table 1). The literature highlights the fact that adolescent mental health is a global issue, and its examination is in the beginning stages in many regions throughout the world, thus revealing gaps and limitations.

Table 1. Barriers to the implementation of mental health literacy in schools

| Authors | Staff/community readiness | Role perception | Time | Mental Health Competence (Including knowledge and/or attitudes) | Gaps | Lack of Training | Limited resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hustus and Owens (2018) | x | x | |||||

| Ekornes S (2017) | x | ||||||

| Evans et al (2019) | x | x | x | ||||

| Vieira et al (2014) | x | x | x | x | |||

| Von der Embse et al (2018) | x | x | x | x | |||

| Long et al (2018) | x | x | x | ||||

| Timmons-Mitchell et al (2019) | x | x | |||||

| Kutcher et al (2016) | x | x | |||||

| Kutcher et al (2017) | x | x | |||||

| Kutcher et al (2013) | x |

Discussion

Need for training

Hustus and Owens (2018) recognised that mental health may not be a priority for educators and administrators. The study included 194 general education teachers, 47 school mental health staff members, and 12 building-level administrators; they attempted to assess the readiness of not only the individuals but of the school communities for the implementations of school mental health initiatives using the Change Orientation Scale. While the study had its limitations, such as the utilisation of two school districts (1 rural and 1 small city), and the population was >90% Caucasian, it revealed an important ‘gap,’ which is the varied perception of teachers versus administrators versus school mental health staff, with administrators rating readiness highest (Hustus and Owens, 2018). If staff members feel unready, there is a concern whether they will be receptive, and if training will be effective.

Ekornes (2017) found that while some teachers felt unready, others were unclear of responsibilities and expectations. Ekornes (2017) examined the concept of perceived competence among teachers, and addressed their emotions and professional responsibility in the promotion of student mental health. A focus group was conducted with 15 students, and questionnaires were completed by 771 teachers. Overall, teachers felt a personal and professional obligation to help students; however, there was a commonality of feeling helpless and inadequate (Ekornes, 2017). Training, however, increased feelings of competence.

As there continues to be a rise in adolescent self-harm worldwide, the need for early recognition of signs of crisis becomes more pressing. Evans et al (2019) discussed the importance of addressing adolescent mental health in schools, raised the point of the increase of adolescent self-harm, and pointed to the importance of staff awareness in schools in England and Wales. However, in order to develop effective training it is necessary to establish what is already in place.

In order to gather this data, surveys were completed by 212 schools in England and Wales by designated staff with knowledge of current practices. In examining the results, 55% of respondents reported some level of training, and of those respondents 50% ranked the training as moderate, while 5% denied any training (Evans et al, 2019). When discussing the barriers to school-based self-harm prevention, the most prevalent were (Evans et al, 2019):

- Lack of time in the curriculum

- Inadequate training

- Limited resources.

Most staff members indicated a desire for increased training in the future.

Overall, staff members want to help students achieve their health and academic goals, but they cannot do so without support. In order to bridge the gap, policies must be created to emphasise the importance of mental health and self-harm prevention. In order to provide treatment and preventive actions, staff members need to have a heightened awareness of the problems, as well as being provided with adequate time and resources for preparation.

Training methods

Adolescent mental health literacy is a global issue, and staff training is in its infancy in many parts of the world. Vieira et al's (2014) study highlighted that no training methods were in place in Brasil and in order to identify and refer children in need, teachers needed to receive proper training. A case-control study was conducted, which aimed to assess teachers' ability to identify and refer students. The purpose of the study was to determine the efficacy of a psychoeducational strategy, using a main longitudinal study and independent-case control with 32 teachers participating (Vieira et al, 2014). It is clear that the teachers are not diagnosing, but rather recognising issues. The authors found that the training only partially helped teachers make the correct identifications in the vignettes. However, it was beneficial for over half of teachers (60%) who could not identify normal adolescent behaviour before training (Vieira et al, 2014). While this study has biases, such as student inclusion, it is a pioneer study in Brazil, and was positively received by staff members who wanted to extend the time and make training relevant to current practice through the discussion of real-life scenarios.

Von der Embse et al (2018) echoed the concerns of Vieira et al (2014) that students with externalising factors are identified more often, leaving students with internalising factors to go unnoticed. Universal training in mental health is useful, but not without barriers. As the authors point out, teachers' concerns to act on screening result and the influence of training on universal screening still needs to be considered (von der Embse et al, 2018). A 90-minute pilot teacher training programme was utilised that sought to address teacher knowledge, as well as assess efficacy and validity of universal screening in terms of determining student outcomes (von der Embse et al, 2018). During training, teachers were educated on (von der Embse et al, 2018):

- Symptoms of mental and behavioural health

- Ways to identify risk and their roles

- The Social, Academic, and Emotional Behavioral Risk Screener-Teacher Rating Scale

- Practicing rating using videos.

A total of 91 teachers (57 in the training group and 34 in the control group) from 4 elementary schools in urban areas in the northeastern United States participated in the study, and they screened 1 158 students. The data showed that teachers that participated in the training versus the control group, had significantly higher acceptability and feasibility scores, and significantly lower system support scores indicating a greater level of independence (von der Embse et al, 2018). Von der Embse et al (2018) also indicated that trained teachers had stronger beliefs regarding their roles in screening and assessment, and an understanding that ongoing monitoring is necessary for students to receive services.

Online training programmes

While in-person training can be a valuable option for some, usage of an online training programme is useful because it is self-paced and accessible to people in multiple locations. Long et al (2018) recruited educators from 10 different states. There was an administration of the Gatekeeper Behavioral Scale before training, then following simulation training and 3-months post training to assess attitudes and intentions. The training course, At-Risk for Elementary School Educators, is an online simulation that allowed participants to go at their own pace; however, most are able to complete the module in 45 to 90 minutes (Long et al, 2018). The simulation included role-playing activities to increase openness and awareness. Overall, participants were satisfied with the training and it helped teachers in effective usage of gatekeeper behaviours (Long et al, 2018).

Timmons-Mitchell et al (2019) examined the effects of the virtual training programme At-Risk for Middle School Educators. Like At-Risk for Elementary School Educators, it was developed by Kognito a company co-founded by one of the authors, Albright. The participants consisted of 33 703 educators who took part in this self-paced simulation, and researchers evaluated their ‘likelihood of engaging in helping behaviours’ and ‘self-efficacy to engage’ using the Gatekeeper Behavioral Scale, with assessment taking place before training and at 3-months post-training (Timmons-Mitchell et al, 2019). Timmons-Mitchell et al (2019) explained that the exercise with the virtual student is complete when the individual gains the student's trust to find out the source of distress and takes appropriate action whether recommendation and/or referral. Overall, the intervention shows statistically significant increases in benchmark behaviour 3-months after training. The authors discuss implications for health behaviours or policy, public health, Healthy People 2020, and conflict of interest, all of which lend to the validity of its usage.

Application of the guide

Promotion of adolescent mental health is crucial in countries such as Tanzania where 63.93% of the population is under the age of 25 (Kutcher et al, 2016). Kutcher et al (2016) address how the gap between poor understanding of mental illness in Africa and limited resources affects youth the most. Using a culturally adapted version of Canada's Mental Health Curriculum Guide, known as the African Guide, they hypothesised whether teachers who had received previous training would benefit from participation in a refresher course in terms of knowledge and stigma surrounding mental health (Kutcher, et al, 2016). A total of 38 secondary school teachers participated in the 3-day training course conducted by the Master Trainers Team, and completed the pre- and post-tests, which measured knowledge and attitudes using a Likert scale. Kutcher et al (2016) found that there was a statistically significant difference in overall knowledge and attitude scores between pre- and post-training, as well as an increased median of comfort score. Additionally, training led to increased referrals, but also self-help with 63% of staff members seeking help for themselves since the initial training (Kutcher et al, 2016). This study shows promise in training, but limitations include:

- No access to the findings of the original study during which the initial training took place

- No explanation of the revisions made to make the AG culturally adaptive.

Kutcher et al (2017) bridge the mental health gap for a rapidly growing adolescent population through follow-up with the 32 staff members who took the 6-month refresher training course, and assessed their knowledge and attitudes 10 and 12 months after the initial training, and looked at the dissemination of the guide to other staff members and students. The survey data shows that 83.3% of teachers reported knowledge improvements, and 87% reported improvements of their own behaviour, while staff reported 100% improvement of student attitude toward those with mental illness (Kutcher et al, 2017). In a year's time, teachers reported increased awareness of high-risk students, students came to find they could approach their teachers for resources and support, and dissemination of the AG grew significantly in terms of in-school discussions and presentations (Kutcher et al, 2017). The data in this article is brief; however, it is indicative of positive improvements in staff knowledge and comfort.

As mentioned previously, the African Guide is an adaptation of Canada's Mental Health Curriculum Guide, therefore, it is useful to examine a study that utilises this training. Kutcher et al (2013) described a study that took place in Nova Scotia of 89 teachers (77 who completed all surveys) for grade 9, who completed a one-day training session using the Mental Health Curriculum Guide. In addition to the aforementioned self-study module and six in-class modules, staff members were given ‘what to do’ strategies, and course content included video clips, facts and myths, and discussions. A 30-question anonymous questionnaire was used to measure knowledge and attitudes pre- and post-testing. Surveys showed increase in both knowledge attitudes, however, attitudes were already high at baseline; the programme received a 4.8 out of 5 rating by participants (Kutcher et al, 2013).

Limitations

The original goal of this literature review was to determine the best methods for promoting mental health literacy among school staff. In truth, in many parts of the globe adolescent mental health is in its infancy, as its influence on personal, professional, and academic outcomes is recognised. Several of the studies listed in this review are pilots or primary studies for their regions, and are an indication of the need for future research. Therefore, at this time, the focus must change from comparison to widespread implementation. Whether it is in the form of in-person seminars, or online simulations, there is a growing need for the support of teachers and school staff members as they are the first line of defence. It is necessary to give them the tools, not to diagnose but to recognise the students suffering in silence before the point of crisis is reached.

Implications for school health

While school nurses, social workers, and counsellors are well positioned to assist students, they do not have the same daily interactions with students that teachers and other educational staff members have. These staff members sit on the frontlines of mental health, as they are the ones best able to build relationships with students, which is vital to a student's health and education outcomes. As outlined by the CDC's 2009 guidelines for ‘School Connectedness’ (Figure 2), it is the ‘strongest protective factor’ against risky behaviours, and ‘was second in importance after family connectedness, as a protective factor against emotional distress’ (CDC, 2009: 5). Drawing on the principles of these guidelines, and the ‘Whole School, Whole Community, and Whole Child’ (WSCC) Model (Figure 3), which places the student at the centre of learning and care, it becomes clear that empowering and educating staff in mental health literacy is essential.

Figure 2. Promoting school connectedness.

Figure 2. Promoting school connectedness.  Figure 3. The WSCC Model (ASCD and CDC: www.ascd.org/wscc)

Figure 3. The WSCC Model (ASCD and CDC: www.ascd.org/wscc)

While issues of mental health are prevalent in schools across the United States, and educational staff members are in an optimal position to best identify students in need, many school staff do not feel prepared to assist (Long et al, 2018). The evidence shows that there is a need for training of staff in recognising signs of emotional and mental distress of students, as there is a lack of familiarity and comfort with identifying students who are suffering. One of the best ways to address this problem is to conduct focused staff training, whether in person or via online simulation. The data at this time does not favour one method of training over another, except to mention the value of online simulation for those schools with limited access, but rather discusses the impact of staff training.

KEY POINTS

- As the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders among adolescents continues to rise, there is a population of young people suffering in silence.

- As these individuals spend the majority of time within the walls of their schools, this environment is ideal for early identification and treatment of problems before the point of crisis.

- However, while most staff members want to assist students many feel uncomfortable or ineffective related to time constraints and lack of training.

- In the examined studies, teachers and other staff overall found training to be positive and felt better prepared to face the challenges. These staff members are not meant to diagnose, but rather to identify students in need.

- Teachers, like school nurses and school counsellors, are a vital part of increasing mental health literacy in schools.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- How might a student ‘suffering in silence’ present in the classroom? How comfortable would you feel approaching him/her to help? What steps might you take?

- What training have you received in mental health literacy in the past (if any)? Do you feel it was adequate/empowering to assist your students? How could it be improved?

- Mental health literacy requires a team approach. How do you view yourself as a member of that team? How does mental health affect you, your students, and the classroom environment?