School nurses are the only health professional with a reach extending to all school-aged children and young people, providing a public health service which is crucial to improving the health and wellbeing of children and young people and reducing inequalities. They lead the delivery of the Healthy Child Programme (HCP) 5–19, supporting children and young people in schools, other education settings including alternative provision, the secure estate, those who are electively home educated and those more vulnerable children who are missing their education (Sutton and White, 2024). Recent reports show a declining picture of child health in the UK and warn that a generation of children and young people are being failed. The needs of children and young people in the UK have increased, with poorer health outcomes compared to other similar nations (Viner et al, 2018). School nursing practice evolves and develops to respond to these changing and increasing needs of school-aged children and young people. However, the capacity of the school nursing workforce to meet needs has dramatically declined (SAPHNA, 2024).

SAPHNA regularly hears from school and public health nurses, they share their stories of innovation and the difference that they are making to the health and wellbeing of school-aged children and young people. However, they express their frustration about the capacity to fully deliver the HCP 5–19, the growing amount of time spent on the acute end of safeguarding (child protection) and the impact this has on their ability to deliver on prevention, promotion, and early intervention. SAPHNA wanted to ensure that policy-makers and influencers hear the voice of the school nursing workforce and that practitioner intelligence plays a critical role in advocating for investment in school nursing to improve the health outcomes of school-aged children and young people and reduce health inequalities. Therefore, between January and March 2024, SAPHNA launched an inaugural survey of school nurses, and their skill mix teams with the aim of using the results to paint a picture of school nursing across the UK. The survey asked questions about the needs of school-aged children and young people, how school nursing services are being delivered, who is delivering services and crucially how school nurses learn from and respond to challenges. The survey provided an opportunity for school nurses to share good practice and innovation. There were 286 UK-wide responses to the survey, 87% of respondents were from England and 96% of respondents were on the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) register. For an exploratory survey of this type, there was a good participation level, with high nurse representation, across the UK.

At the same time as gathering practitioner intelligence, SAPHNA asked a parliamentary question to the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care about how many full-time equivalent qualified school nurses are working in a public health-commissioned school nursing service delivering 5–19 services in each local authority area. The response (below) evidences the absence of robust data at a national level which means that it is not possible to determine an accurate number of qualified school nurses working in school nursing services with the primary purpose of delivering the HCP 5–19.

The parliamentary response did confirm SAPHNA's concerns about the postcode lottery of provision across England. A range as low as 0.11 per 1 000 pupils in the Southwest (meaning a school nurse having to care for 9 090 children) to 0.35 per 1 000 pupils in the West Midlands (meaning a school nurse caring for 2 850 children).

Data gathered in the survey shows 82% of respondents indicated there was not enough staff to deliver an effective school nursing service. The results revealed an aging workforce, over a third of qualified school nurses responding to the survey reported to be aged 51 years and over. Almost half of those school nurses plan to retire in the next 3 years with a loss of expertise and experience.

Health issues for school-aged children and young people.

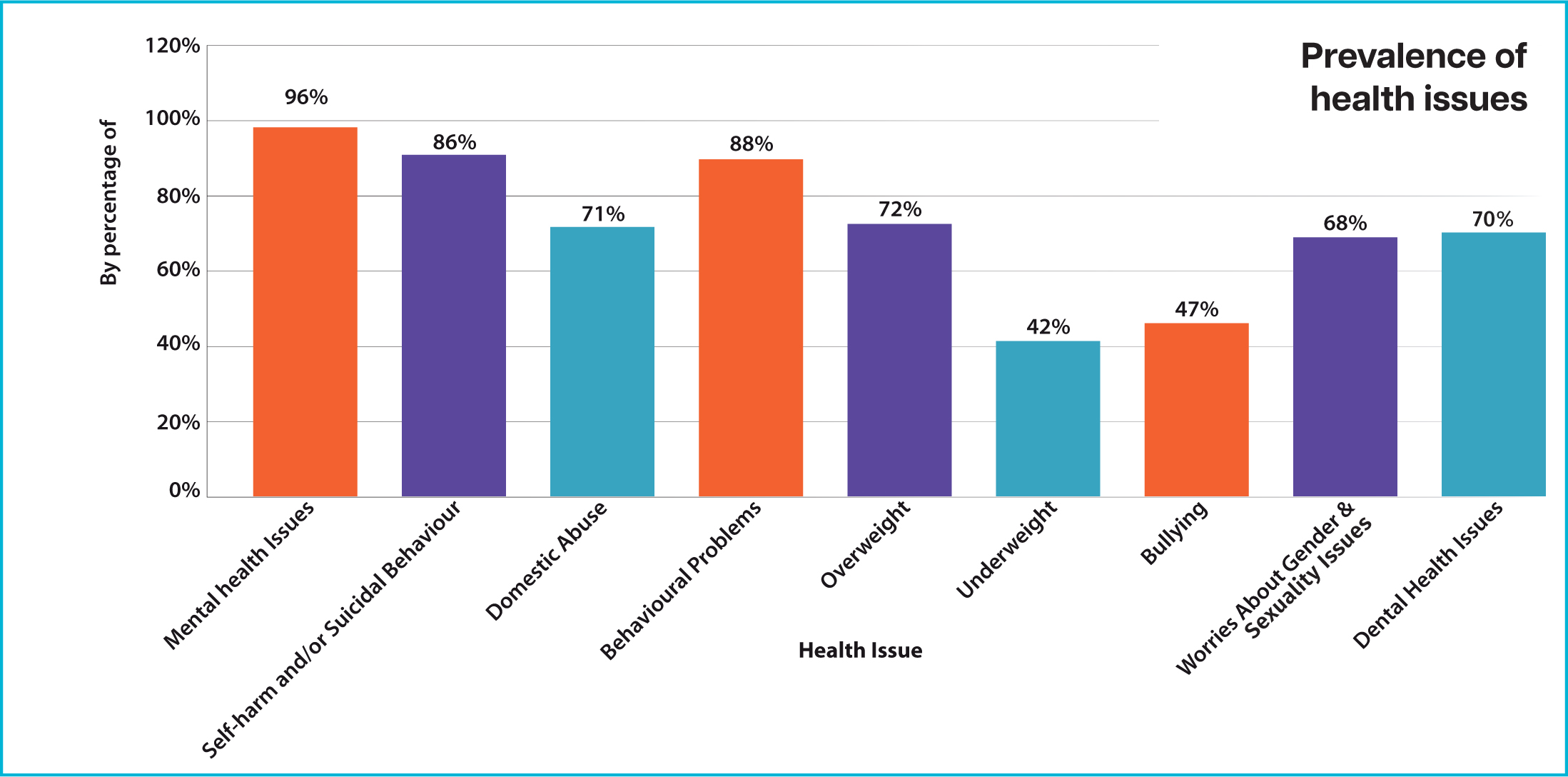

The State of Child Health report in 2020 revealed that performance against key indicators had worsened or stalled, there have been increases in mental illness, child poverty, youth violence, children on child in need and child protection plans (Viner et al, 2018). In SAPHNA's survey, respondents indicate that they perceived significant increases in prevalence across most areas of health and wellbeing. The prevalence of some issues such as bullying had less of an increase; however, school nurses were keen to point out that ‘this could be due to poor school attendance among young people.’

In qualitative responses, school nurses spoke about increased issues around children not being ‘school ready,’ and an increase in parents and carers seeking support for school avoidance, school exclusions and advice about elective home education. School nurses described increasingly complex family situations due to the impact of the cost of living, housing issues, parental mental health, safeguarding, and exploitation beyond the home. Many respondents commented how this picture of increasing complex need is affecting the amount and profile of their work. Approximately 40% of school nurses indicated that they spent over half of their working week supporting children and young people on child protection plans. They described having a ‘holding’ role, supporting children and young people, and their families while waiting for specialist health services or other support services.

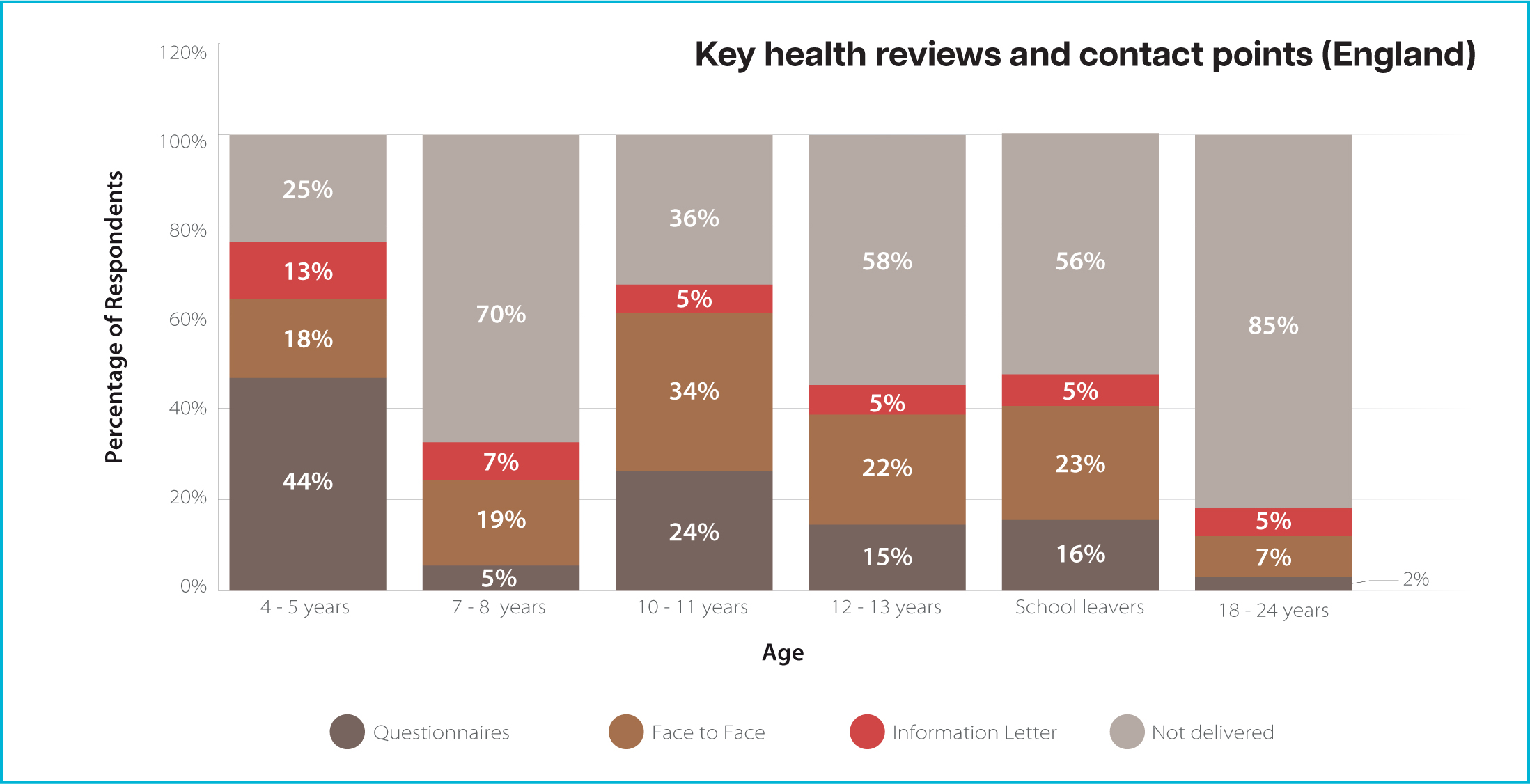

School nurses reported that the increase in the numbers of individual children and young people who need support means that there is less capacity in services to deliver on their wider public health role. The universal offer for HCP 5–19 is key for prevention, promotion and early identification of issues and offering early intervention. However, the percentage of respondents indicating that health reviews at key contacts points are not offered due to capacity evidences missed opportunities for public health interventions and increasing risk of having to address issues upstream, which is costlier financially and more detrimental to the outcomes for a child or young person.

The survey asked respondents about the service offer for key public health issues including smoking and vaping, alcohol and drugs, physical health, healthy lifestyles, emotional health and wellbeing and sexual health and wellbeing. Eighty-eight percent of respondents indicated that their service provided health promotion, advice and interventions for emotional health and wellbeing. However, for other issues, between a quarter and a third of respondents indicated that their service did not provide any offer. This evidences further missed opportunities and raises concerns about how accessible, visible, and responsive services are to meet the needs of school-aged children and young people.

Impact on the workforce

The survey data revealed the resilience and determination of the workforce. Seventy-seven percent of respondents reported that they enjoy their roles even though only 18% reported that there is enough staff to deliver services. One nurse described that ‘we provide an excellent service to the children on our caseloads, but we are not offering a good level of universal support’. Less than half of respondents indicated that children and young people have access to the support that they need, in a timely way. School nurses described their work as reactive rather than proactive, constantly firefighting. One school nurse felt that ‘we concentrate more on fixing problems rather than offering early intervention and health promotion’. Words and phrases including detrimental impact on staff wellbeing, loss of job satisfaction, sense of frustration was commonplace in the survey.

Innovation and good practice

While the survey results paint a gloomy picture of school nursing in the UK, the workforce continues to respond to the challenges it faces. The survey showed evidence of innovation and good practice, ranging from focusing delivery in key areas of need, including developing resources for mental health promotion and targeted support packages for more vulnerable groups including young carers and homeless families. School nurses have embraced technology to extend choice to children and young people about how they access services, including use of virtual clinics, text messaging services, use of websites to provide information and webinars to deliver workshops.

School nurses demonstrated a willingness to be involved in, and an awareness of a need for research relating to children and young people's health and the role of the school nurses. Respondents engaged in research at several levels, national and local studies and local research groups including studies about school nurse working practices, resilience programmes and asthma-friendly schools. In local areas, school nurses canvassed children and young people's opinions of what was needed in relation to their health, and how they would want this information delivered.

What next?

The survey paints a candid picture of the school nursing workforce under significant pressure and confirms the findings of ‘A school nurse in every school’ report which bought together over thirty strategic partners, drawn from health and care systems to explore and define the challenges for school nursing and find solutions (SAPHNA, 2024). At SAPHNA, we believe that it is not too late to change direction and have several recommendations to the new government.

SAPHNA is maintaining momentum to ensure that school-aged children and young people receive the school nursing services that they deserve. The survey report was launched on the 8th of October at a prestigious event in the House of Lords hosted by Baroness Frances D'Souza and attended by key strategic partners and many MPs. Following the event at the House of Lords, SAPHNA hand-delivered their petition, ‘A School Nurse in Every School,’ to Number 10 Downing Street. The petition, which has garnered widespread public support, calls on the government to ensure that every school in the UK is staffed with a qualified school nurse to meet the growing health needs of children and young people. The petition highlights the severe shortages in school nursing staff and the critical role that these professionals play in supporting the health and wellbeing of pupils. Since the event, Neil Duncan Jordan, MP for Poole tabled an Early Day Motion which records the views of individual MPs and draws attention to the campaign for ‘A School Nurse in Every School.’ This is attracting support from other MPs and the hope is that the issues can be debated in the House of Commons at a future date.

Join our campaign and sign our petition at: https://www.change.org/ASchoolNurseinEverySchool