The school health service, delivered by school nurses who have successfully completed the specialist community public health nurse qualification and skill mix colleagues, is the only frontline NHS service linking health and education, providing an essential Public Health service for children, young people and future generations and addressing inequalities. In 2004, the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) created a third part of the professional nurse register for all specialist community public health nurses that included school nurses, health visitors and occupational health nurses.

Historically school nurses emerged at the same time as health visitors during the Victorian era in Britain, with a role in gathering information in the school setting. The early tasks of school nurses arose out of the need to improve the health of children living in poverty (The Queen's Nursing Institute, 2017).

In the 2010 Marmot Review, Fair Society Healthy Lives, emphasis was placed on a range of factors that impact the health of the nation, including ill-health prevention. A further review in 2021 maintains the importance of the emphasis on early intervention to prevent health inequalities (Marmot, 2021). Many of the early aims of the school health service remain applicable today.

‘School nurses utilise their clinical judgement and public health expertise to identify health needs early, determine potential risk, and provide early intervention to prevent issues from escalating.’

The guidance for health visiting and school nursing service delivery models states that school nurses offer year-round support for children and young people both in and out of school settings. School nurses utilise their clinical judgement and public health expertise to identify health needs early, determine potential risk, and provide early intervention to prevent issues from escalating (Public Health England, 2021).

Central London Community Healthcare NHS Trust (CLCH) provides the school health service in six different boroughs, each with its own set of local authority commissioners. The delivery model was based on historical practice and had not been reviewed in many years. Through an action learning set run by the nurse consultant for public health and the interim clinical quality lead for children and families, it was reported that the staff felt undervalued and overworked. In October 2021 a programme of work was commissioned by the chief nursing officer (CNO) and chief operating officer (COO) in response to that feedback. The aim of the programme of work was:

Programme delivery

A Strategic Overview Group (SOG), chaired by the CNO and the COO, was set up to provide the strategic direction for the programme, and to provide support to the programme lead and chairs of working groups.

An outline project plan was developed with five workstreams identified. The SOG agreed on the objectives proposed by each of the five working groups and monitored progress at monthly meetings. A summary report on progress was also presented to the Trust-wide Children's Board.

The five working groups are listed below:

The groups had representation from each borough and each role within the skill mix structure, alongside corporate colleagues to support the quality improvement and shared governance approaches used within the trust. The main focus of the project was the core activities of the school health service.

As the programme progressed, it was agreed that there would be three phases:

This case study will focus on Phase 1 activities and outcomes.

Approach/tools

Staff engagement

Staff engagement was key to this project. Representation was requested for each role in the skill mix and from each borough. Attendance varied at times owing to workload demands. However, all outputs were cascaded through the school health team leads for discussion with teams, through attendance at each area team meeting by the project lead and the delivery of several teams-based webinars where the progress of the working groups were reported, and opportunities given for staff to ask questions. The culmination of staff engagement was three ‘Launch of the Time to Shine project’ webinars delivered in June and July 2023.

There was also engagement with children and young people. Details are provided under the key achievements section.

Benchmarking

Several benchmarking activities took place, with comparisons drawn between CLCH and three other school health service providers. A review of the literature highlighted a lack of published information on school health workforce modelling and service delivery. The discussion and eventual clinical model proposed was a combination of information gathered externally and views of the service and project leads internally. Regular contact was made with the chief executive officer of the School and Public Health Nurses Association (SAPHNA) to outline the project aims and for support and expert advice as the project progressed.

Demand and capacity tool

A newly created trust-wide demand and capacity tool was adapted to suit the requirements of the school health service. Great support was provided to the project on this element by the population health lead analyst. The tool describes the routine activities of the different members of the skill mix team and the agreed core clinical activities are described in Table 1. This had a ‘current offer’ element and as the new model emerged a ‘future offer’ was plugged into the tool to outline the service model required for each borough. The tool took account of the clinical activities, the average time taken for each activity, the administrative time and any associated travel time. The tool also allowed for some variations in activities due to the range of different commissioning specifications.

| Type of activity | Clinical activity |

|---|---|

| 1:1 complex | Children in need |

| 1:1 complex | CPC – F2F – child (health review) |

| 1:1 complex | CPC – initial case conference |

| 1:1 complex | CPC – review case conference |

| 1:1 complex | CPC – attendance at core group 6 weeks |

| 1:1 complex | EHCPs |

| 1:1 complex | Pupil referral unit |

| 1:1 complex | Youth justice service |

| 1:1 non-complex | Hearing and vision screening (test/retest) |

| 1:1 non-complex | Reception (5-year-olds) – health reviews |

| 1:1 non-complex | Reception (5-year-olds) – handover |

| 1:1 non-complex | Year 6 transition health review |

| 1:1 non-complex | Team around the child/family |

| 1:1 non-complex | Year 9 – health reviews |

| 1:1 non-complex | Health care plan meeting with parent |

| 1:1 non-complex | Incontinence support – following referral |

| Education | Healthy weight and eating HP session |

| Education | Hand hygiene |

| Education | Oral hygiene |

| Education | General keep healthy (KS2) – junior citizens |

| Education | Sexual health including puberty, menstruation, pregnancy (prim/sec) |

| Education | Independence to manage healthcare needs (primary) |

| Education | Mental health – primary |

| Education | Smoking, drugs and alcohol |

| Education | General health education |

| Education | Intro to school health service |

| Education | Mental health – secondary |

| Clinic | NCMP – (reception/year 6) |

| Clinic | NCMP – admin |

| Clinic | Primary school drop-in/coffee mornings |

| Clinic | Secondary school drop-in |

| Other | School visit including liaison with staff/school referrals reviews (including training of education staff) |

| Other | Referral processing and follow-up |

| Other | Emergency department attendance follow-up |

| Other | Referral follow-up primary |

| Other | Referral follow-up secondary |

| Other | Triage/duty |

Complexity tool

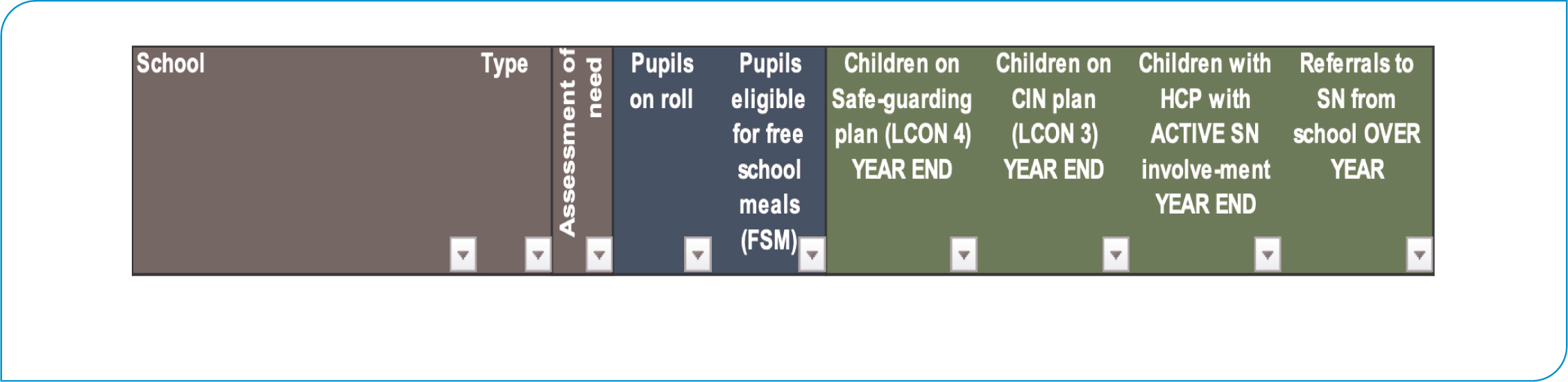

A bespoke complexity tool was developed with support from a CLCH population health lead analyst. The aim was to see whether we could develop a formula for identifying high and low complexity demands per school. Information was gathered from each local authority public website for school name, number of pupils on the roll, and number of pupils in receipt of free school meals. Then each of the borough teams added local information about the number of children on a child protection plan, number of children in need, number of children with medical conditions requiring active school nurse involvement and the number of referrals received by the service in the last year. Figure 1 highlights the criteria included in the tool. The teams were also asked to include their own assessment of complexity for each school, describing it as high or low (complexity), based on their local knowledge of the school requirements. This local team data correlated well with the tool outcome on complexity once all the columns were populated.

Each team had easy access to the number of children per school on a child protection (CP) plan and the number of children per school on a child in need (CIN) plan. Identifying children with Active School Nurse involvement required manual counting and reliability was variable as was collation of the number of referrals to the school nurse from the school. However overall, it was felt that the complexity tool indicated how the demand for the service varied by school. It is also possible to review and update the data within the tool as needs change (e.g. number of CP plan cases varies across the year).

‘A bespoke complexity tool was developed with support from a CLCH population health lead analyst. The aim was to see whether we could develop a formula for identifying high and low complexity demands per school.’

Information on eligibility for free school meals indicator (FSM) was readily available on local authority websites. Figure 2 highlights the average eligibility and was taken as a reasonable indication of deprivation and therefore higher demand on the school health service (Ilie et al, 2017).

Once all the data was entered, the complexity tool indicated the demand, in days (full or partial) and therefore nursing time required to deliver the service to each school. The use of this information was intended to move the school nursing offer from a generic offer to a tailored one, to ensure scarce resources were distributed most efficiently.

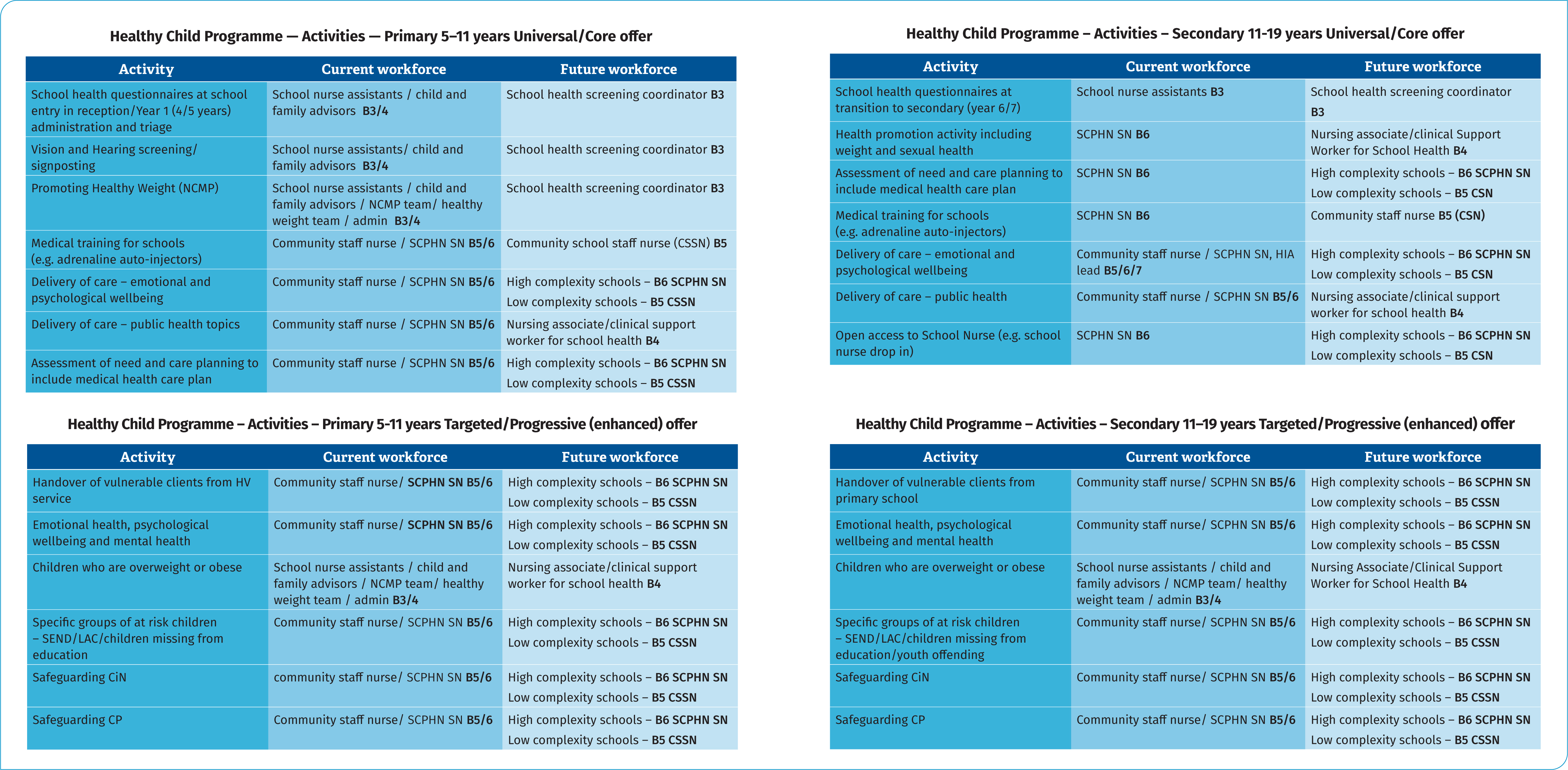

The clinical model

The clinical model and allocation of activities were defined using the Healthy Child Programme 5–19 years (Department of Health, 2009). Consideration was also given to the recommendations from the School and Public Health Nurses Association (2021) publication ‘School Nursing: Creating a healthy world in which children can thrive. A Service Fit for the Future 2021’. Figure 3 on the next page outlines the activity, the existing offer and the proposed (now agreed) way forward.

New service model

Using the details from the demand and capacity tool and the complexity tool each clinical service unit senior team, working with the population health lead analyst, developed a skill-mix service model for their borough. The proposed changes were then presented to trust-wide governance meetings which oversee any clinical staffing change proposals. All models were approved.

To offer this model it was essential to review the roles and responsibilities of each member of the skill mix team. The variation between boroughs was highlighted during this part of the project. To standardise the offer, we agreed to have a dedicated screening and administrative post, the focus of which would be the commissioned public health screening requirements for the National Childhood Measurement Programme (NCMP), and vision and hearing screening. There would be a new post of a nursing associate in school health (achieved via the apprentice nursing associate route) or a clinical support worker whose role would be focused on health promotion and some individual and small group work with children as delegated by the school nurse. It was felt that this skill mix would allow both an efficient delivery of the service and a clear career pathway from nursing associate apprentice to school nurse (SCPHN). This also aligned with CLCH anchor organisation objectives to be a positive local employer and to increase apprenticeship opportunities.

As part of this project, each job description within the skill mix was reviewed and updated, clearly outlining the differences between roles and responsibilities for each role and pay grade. This activity took place in interactive workshops with representatives from each group of staff, following which the revised draft document was sent to all staff in that role to allow an opportunity to comment. The final draft version was then reviewed by the trust's job evaluation team. Once fully approved, the job descriptions were shared with each team and added to a dedicated Time 2 Shine page on the internal intranet.

Key achievements of the project

A new CLCH clinical model was developed and approved, and a borough-specific service model was agreed upon, as described above.

In the children and young people engagement group, a video was developed and supporting materials (e.g. pens, water bottles) were purchased, which were used during visits to some local schools to talk about the school health service and the project. Ultimately a children and young people's (CYP) user group was set up to continue after the life of the project to support the ongoing work of the trust to hear the views of children and young people.

A comprehensive training and competency assessment framework (Training Triangle) was developed for the community school staff nurse role. It was intended for use with existing staff and to be incorporated into induction for new starters.

A new case conference framework was developed, including a health needs assessment. This element of the project has previously been published (Livsey, 2023)

Following a pilot in one area, a positively evaluated mental health toolkit training package was developed and delivered to all nurses in the service. This gave them increased skills to manage non-complex mental health issues with children and young people.

To advance the school nurses' knowledge and skills in supporting mental health with children and young people. a shared governance project considered what other tools were available for the assessment of mental health. A decision was taken to use the Revised Children's Anxiety and Depression Scale tool (RCADS) (Ebesutani et al, 2012), which was piloted in two of the boroughs. This approach was accepted by staff and a plan to roll out the training across all areas was developed. The scoring on completion of the screening tool allows the School Health team member to decide whether onward referral to a specialist service is required.

The original school health caseload standard operating procedure document, which supports the management of the electronic patient record system, was reviewed, updated and cascaded to teams.

Ongoing activities

As Phase 1 of the project concluded in July 2023, the project lead was aware that a few elements of the project had not been fully delivered. It was agreed to take those elements forward within Phase 2 and a school health model implementation group was established.

A pilot project was started in April 2023 to test a new centralised Duty process for the service. Once the evaluation of the pilot is written up, the findings will be shared with the implementation group for consideration of cascading to all boroughs.

Training and competency frameworks are being developed for other roles within the skill mix team. There is a linked project in progress to develop an assessment framework, to validate those colleagues who are in Band 6 school nurse roles without a SCPHN qualification.

It was highlighted that work was required to update the electronic patient record systems to support efficient record keeping and therefore a separate project was commenced to revise and update clinical templates, incorporating the correct SNOMED codes, to ensure that school health activities could be recorded accurately and reported internally and externally.

As part of the implementation phase, it was agreed that the allocated school nurse would talk with education colleagues to explain the change in the allocation process, using their annual partnership agreement meetings to take those conversations forward.

Once the initial model was developed conversations started with children's services public health commissioners about the clinical and service model including any financial implications.

Conclusions

School health is an essential service for children, young people, families and education staff. Visibility in schools is therefore key to delivering a quality service to children and young people and addressing inequalities, as well as developing positive working relationships with all stakeholders. As the reader can see, there is much still to do to fully implement the new way of working, especially the updated approach to safeguarding health needs assessment and conference attendance. Due to the differing commissioning arrangements, it is understood that the changes will be adopted by the service teams at different intervals. However, we believe that the excellent staff engagement, which has been maintained within the implementation group continues to shape project outcomes and the way forward. We have not underestimated the financial challenge from the commissioners' perspectives as local authorities struggle to deliver on all the public health priorities. The members of the implementation group hope that by presenting the details within the demand and capacity tool and the complexity tool we can evidence the rationale for positive investment in the future health and wellbeing of the children and young people in our place-based service areas.