In 2021, the Chief Nursing Officer for England created the first ever research strategy for nurses, ‘Making research matter’, which aims to:

The strategy's vision is to ‘create a people-centred research environment that empowers nurses to lead, participate in, and deliver research, where research is fully embedded in practice and professional decision-making, for public benefit’ (NHS England, 2021).

To achieve this, nurse research leadership development is essential and health visitors play an important role in advancing research for children and families within the community setting. Despite this, nearly 3 years later, nurses are still under-represented in research, this is especially true for health visitors.

In a recent Institute of Health Visiting (iHV) blog, Baldwin emphasised the need for more health visitors to engage and lead research (iHV, 2024a). This is because, despite nurses and health visitors making up the largest staff group in healthcare (NHS Digital, 2023), they remain under-represented in leading and undertaking research. In 2018, the Council of Deans of Health reported that the proportion of clinical academics from a nursing, midwifery and allied health professional background was less than 0.1% of the workforce (Baltruks and Callaghan, 2018). This is minute when compared to the medical workforce, where clinical academics made up around 4.6% of the workforce in the UK (Medical Schools Council, 2017).

More recently, a review carried out by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) of their portfolio of studies for the Research for Patient Benefit Programme (RfPB) reported that the majority of applicants funded in lead and co-applicant roles were medically qualified (41%), with nurses and midwives making up only 8% of the successful applicants (NIHR, 2024).

To address some of these disparities, there is now a national drive for strengthening and expanding nurses' contribution to health and care research. The NIHR RfPB programme launched a series of highlight notices aimed at under-represented disciplines and specialisms, with a special notice specifically inviting applications led by nurses and midwives (NIHR, 2024). Health visitors, through their unique role, are ideally placed to take advantage of such initiatives and identify research which could contribute to improving outcomes for babies, children, families and communities that they work with. However, in the iHV State of Health Visiting 2023 survey, 74% of health visitors stated that they were not actively involved in research.

Health visitors are the only professionals who have universal access to every newborn and their family in the community as part of the national Healthy Child Programme (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID), 2023a). They also have an extended period of contact with families (from pregnancy to 5 years after birth), enabling them to build meaningful therapeutic relationships with families and provide continuity of care, which is one of the fundamental features of what makes health visiting successful (Cowley et al, 2013; Cowley and Bidmead, 2021). Additionally, health visitors are the most trusted source of advice for parents with high levels of acceptability (Morton, 2024). This therefore puts health visitors in an ideal position to identify research which aligns with babies', children's, parents' and families' needs.

As specialist community public health nurses (SCPHN), health visitors not only work with individual babies, children and families, but also work with communities to improve the health of populations. In addition to this, the health visitor's role covers a range of diverse areas, including health, education, social care, and involves a wide range of public health functions, child health and protection, and professional nurse leadership (Baldwin, 2012). While professionals such as social workers, general community nurses, public health workers, children's centre workers and outreach workers may all be involved in providing a range of activities, it is the breadth of the role and universal reach that makes health visiting a unique profession (Malone et al, 2003; Cowley, 2002). Health visitors, therefore, have the expertise to work across professional boundaries to identify research needs and work with professionals from multidisciplinary backgrounds to address the research needs of babies, children and families.

In 2022, the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) published the new standards of proficiency for SCPHNs, which recognises their specific roles and the need for role-specific standards (NMC, 2022). Research is embedded in these standards, highlighting the requirement for participation in research, identification of research gaps, use of evidence-based practice, and the sharing of lessons learnt and outcomes of research (see Box 1).

Standards of proficiency for specialist community public health nurses relating to research (NMC, 2022)

Sphere of influence B: Transforming specialist community public health nursing practice: evidence, research, evaluation and translation

The role of the health visitor in research, as highlighted in the standards of proficiency, is focused at all levels: leading, delivering and participating. In turn, this aligns well with the four principles of health visiting, which were originally devised by the Council for the Education and Training of Health Visitors (CETHV, 1977), but remain relevant to contemporary health visiting practice (Cowley and Frost, 2006).

Health visitors can make valuable contributions to research through the connections they have with the local communities and populations. They can be a conduit between researchers and the population. Due to the unique role of the health visitor seeing every family with a child under the age of 5 years, with no referral criteria, they can raise awareness of research opportunities with families. They can also support researchers to access local community groups of interest, which makes health visitors instrumental in leading, participating in, and delivering public health research, thus contributing to the national nursing research agenda.

Roles health visitors could have in research

Contributing to research can take place in a number of ways; it is not always about leading research. To provide some ideas and inspiration on how health visitors can engage with research, several research roles and activities, as part of a study are discussed here.

Helpful research resources for health visitors

Overcoming barriers/challenges to engaging with research

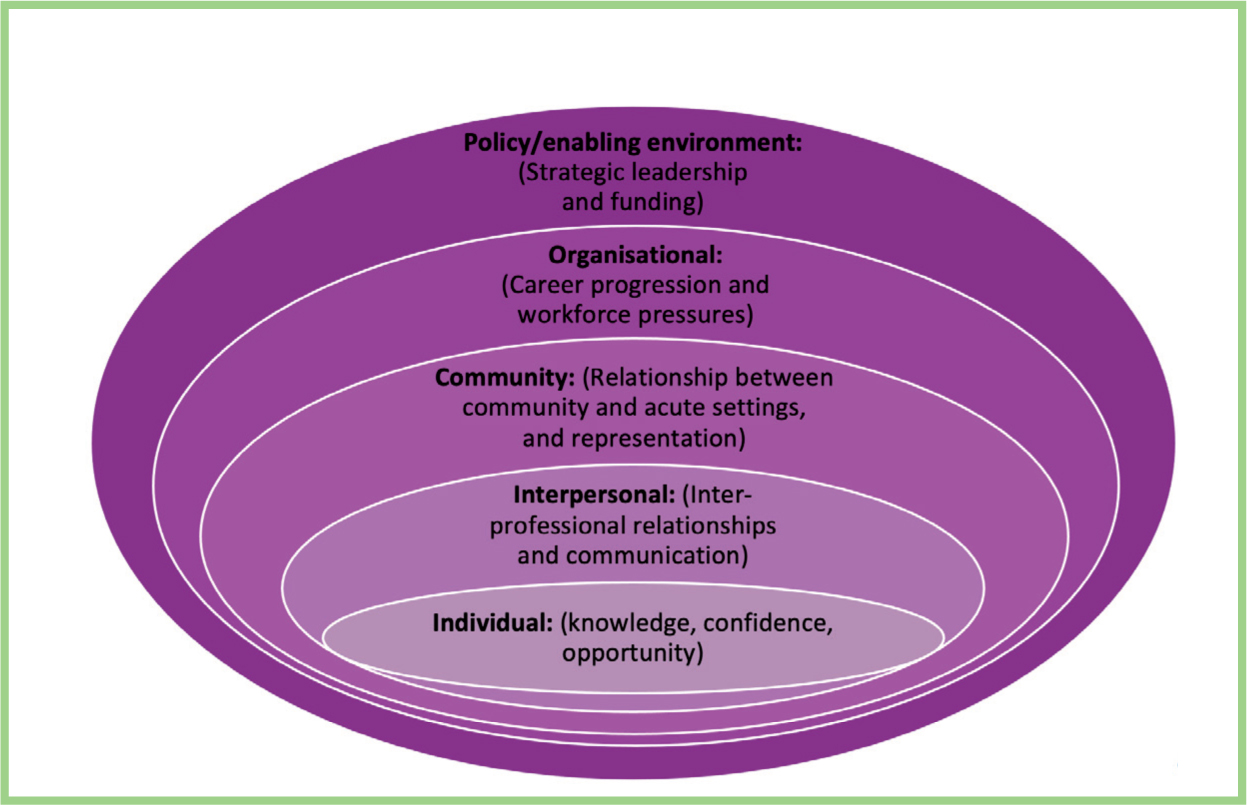

Despite the benefits of health visitors being involved with research, the uptake of research remains low (Medical Schools Council, 2017; NIHR, 2024). In this section, the possible barriers and challenges are considered at various levels (individual, interpersonal, community, organisational and policy level) using the socio-ecological model (Figure 1), with a view to exploring ways to overcome the barriers and challenges.

Individual: Knowledge, confidence, opportunity

As with any topic, it can be misleading to attribute findings to whole population groups. However, several common themes arise when research is discussed with health visitors and their reasons for not engaging with research are explored. These include knowledge, confidence and opportunity (0–19 Research Network, 2024). Nurses can be hesitant to be involved in research as it is perceived as an academic pursuit, using language that is very different to the language of nursing (Hendricks and Cope, 2016). It is also often focused on medical interventions and clinical trials, which makes it appear remote and divorced from health visiting and the world of public health.

A recent evaluation of the 0–19 Research Network (Yorks and Humber) supported by Strategic Priorities Funding from the NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) (Yorkshire and Humber), showed that 25% of network members were not confident in their own research/evaluation skills, with 37% having ‘little confidence’, and very few reporting to feel confident (0–19 Research Network, 2024).

The feedback on leading others in research in practice was similar, with 58% reporting not knowing who to talk to about being involved in research/evaluation. This evaluation also highlighted that many health visitors had little formal training in research, which may have only been part of their pre-registration or post-registration training. This resulted in the health visitors reporting limited confidence in their knowledge and understanding of research. Having low levels of confidence, knowledge and understanding about research can lead to imposter syndrome and the feeling that research does not apply to them (0–19 Research Network, 2024).

To overcome these barriers, health visitors need to be supported to ensure that they prioritise their own research development, by:

Interpersonal: Inter-professional relationships and communication

Research, no matter what the topic or discipline, when conducted in the most robust way, involves collaborations. In public health, this means, not just between participants and researchers, but also different disciplines and professions working in the topic area.

This can be both an enabler and barrier for health visitors as they work with several different professionals including midwives, GPs, social workers, teachers and local authority services (DHSC, 2015). This could allow a rich bed of knowledge to be pulled upon to conduct research. However, there are also barriers, one of which is communication between the different professional groups. The lack of communication between the professionals, not only within health care but partner agencies too, is well documented in serious case reviews (Garstang et al, 2021).

To overcome these barriers and maximise the enablers, health visitors can:

Community: Relationship between community and acute settings, and representation

While clinical academic careers within nursing are central to designing and pioneering new innovations in service, the relationship between academic institutions and community healthcare settings may not be as clear, or indeed robust, as is with acute settings.

Currently, there are also very few clinical academics within the UK health visiting workforce, which can pose a number of challenges. For example, the current NIHR clinical academic fellowship panels rarely have any health visitor academics. This means that health visitors are not equally represented in the selection committee when compared to midwifery or other specialist fields of nursing. This can put potential applicants at a disadvantage, especially if the study includes health visiting practice, policy and interventions. While further work is needed here at a policy level, more health visitors need to start considering clinical academic careers to fill this gap in the future. Connecting with organisational Research and Development (R&D) departments could be the first step to identifying partnership opportunities to work with Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and explore options for clinical academic careers.

There are now a number of such NIHR fellowships available at different academic levels, which health visitors may be eligible to apply for (more information can be found here: https://ihv.org.uk/our-work/research/research-funding-opportunities/).

To overcome these barriers and maximise the enablers:

Organisational: Career progression and workforce pressures

A barrier in the aspect of organisational structure of health visitor services and training is a lack of a clear model of career progression and a lack of flexibility in the ratio of clinical practice to research. Further findings from the 0–19 Research Network evaluation showed that, for those who are interested in research, there is a clear lack of opportunity (0–19 Research Network, 2024). This is partly due to research having a medical model focus and the difficulty of obtaining ethics approval for conducting research with babies and young children or vulnerable populations. The other barrier is time and capacity with a workforce shortage of around 5000 health visitors across the country (iHV, 2024b). There is increased pressure on the remaining workforce to complete key performance indicators and safeguarding contacts, with limited opportunity to release health visitors for additional roles and opportunities such as research involvement.

Research leaders within the organisation may be able to help. In 2018, NIHR introduced the 70@70: The NIHR Senior Nurse and Midwife Research Leader Programme to strengthen the research voice and influence nurses and midwives in health and social care settings (NIHR, 2019). Becoming familiar with local and national health visiting research leaders/champions will provide a way to learn about research opportunities and access relevant support to influence barriers at an organisational level.

To overcome these barriers and maximise the enablers, health visitors can:

To overcome these barriers and maximise the enablers, organisations can:

Policy/enabling environment: Strategic leadership and funding

As highlighted in the previous section, there are insufficient post-doctoral research posts; and a mixed economy of funding from universities, the NHS, central government and research funding bodies.

Recommendations from the iHV (2024b) State of Health Visiting report gives a clear call to action for the government to improve research capacity and involvement for health visitors by ending the current postcode lottery of health visiting support to ensure that ‘health visiting research, workforce development and the sharing of evidence-driven models of best practice are supported’ (p.8).

To overcome these barriers and maximise the enablers, there is a need:

See Box 3 for a summary of suggestions for overcoming the barriers and challenges of health visitor involvement in research.

Suggestions for overcoming barriers

Individual

Interpersonal

Community

Organisational policy/enabling environment

Policy

What next?

The need to strengthen health visiting participation in research is clear. Health visitors are ideally placed to be active in research and make significant contributions to improving outcomes for babies, children, families and communities, and advancing the health visiting profession to ensure that it is fit for the future. The unique nature of the health visitor role not only allows health visitors to identify research priorities, but also to engage with the public to be involved in research, reaching marginalised groups, as well as working with a wide range of multidisciplinary professionals.

However, the barriers and challenges for health visitors engaging and being involved in research should not be overlooked. There are many actions that individuals can take to improve their own knowledge and confidence in research, as well as looking for research opportunities. Nevertheless, without national leadership, support of local managers and organisations, and the conducive systems in place to enable research, the capacity and capability within health visiting will not grow.

Investment into health visiting and public health research is needed to ensure that the untapped potential of health visitor research is not lost.