There is a growing literature base indicating that school nurses are well placed to support children and young people with mental health needs (Smith and Bevan, 2020; Taylor-Beirne, 2022). Although there are identified training gaps and some school nurses lack confidence in this area, there is recent evidence to suggest that, with the right training, school nurses can be effective at identifying and supporting children in need of emotional and mental health support (Ravenna and Cleaver, 2016; Smith and Bevan, 2020; Taylor-Beirne, 2022). As a result, accredited, evidence-based training courses should be offered to school nurses to improve their confidence and increase their knowledge of mental health issues (Ravenna and Cleaver, 2016; Taylor-Beirne, 2022). This highlighted need is within the context of increasing child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) waiting lists, and heightened levels of poor emotional wellbeing after the COVID-19 pandemic (Local Government Association, 2023; Young Minds, 2023).

To effect change and target this gap in service provision, Central London Community Healthcare NHS Trust (CLCHT) implemented a School Nursing Quality Improvement Project (QIP), ‘Time to Shine’. Offering the 2-day Youth Mental Health First Aid England (MHFA) training package to all school nurses within the Trust was a key part of this project. The Youth MHFA course provides training on topics including identifying and supporting young people with common mental health disorders, as well as suicide, psychosis and eating disorders. Participants also learn how best to respond when someone is struggling with or disclosing their mental wellbeing. This course was selected as appropriate for the QIP due to accessibility of instructors within the organisation, and an already positive evidence base for its use in other professional arenas (Morgan, 2018). Another instructor was funded by CLCHT as part of this project.

Aims

As a QIP, there was investment from the organisation, with time taken out of direct clinical school nursing work for those to attend a 2-day training course, as well as financial investment in training a new instructor and the cost of training materials. Therefore, it was agreed that the effectiveness of the training would need to be monitored, to ascertain if it was an appropriate investment and allocation of NHS resources. The improvement project questionnaire focused on the experiences of school nurses attending the 2-day Youth MHFA training, capturing whether their levels of knowledge, confidence, and understanding of the school nurse role in relation to supporting children and young people's mental health, had changed as a result of the training.

Methods

This was a mixed-methods audit as the questionnaire included quantitative and qualitative data, which captured the school nurses' experience on the course in relation to their knowledge of mental health disorders and their levels of confidence working with young people struggling with mental health difficulties.

Participants

There were three courses run over a 6-month period. A total of 44 school nurses were trained during this time, and are included as participants in this study. Course cohort size ranged between 10 and 16 school nurses in each course delivery.

School nurses ranged in qualification and experience, including community staff nurses, specialist community public health nurses, and senior school nurses (e.g. team leads and high impact leads). The school nurses attended the courses with other healthcare professionals within CLCHT, who are not included as participants in this study.

Materials

The project utilised the Youth MHFA England training package, course content, schedule, and resources, which were accessible to qualified instructors within CLCHT. The additional materials including the Youth MHFA workbook for all participants was also funded by the Trust. The training rooms were provided by the CLCHT Academy to avoid additional costs.

For data collection, it was decided the computer programme (AMAT), typically used for internal audits within the trust, was not viable for this project as the questionnaires required completion immediately before and after the training. The training rooms lacked sufficient IT equipment to provide the participants with access to electronic completion of the survey. Therefore, paper questionnaires were the optimal method of data collection as these could be given immediately to participants at the start and end of training.

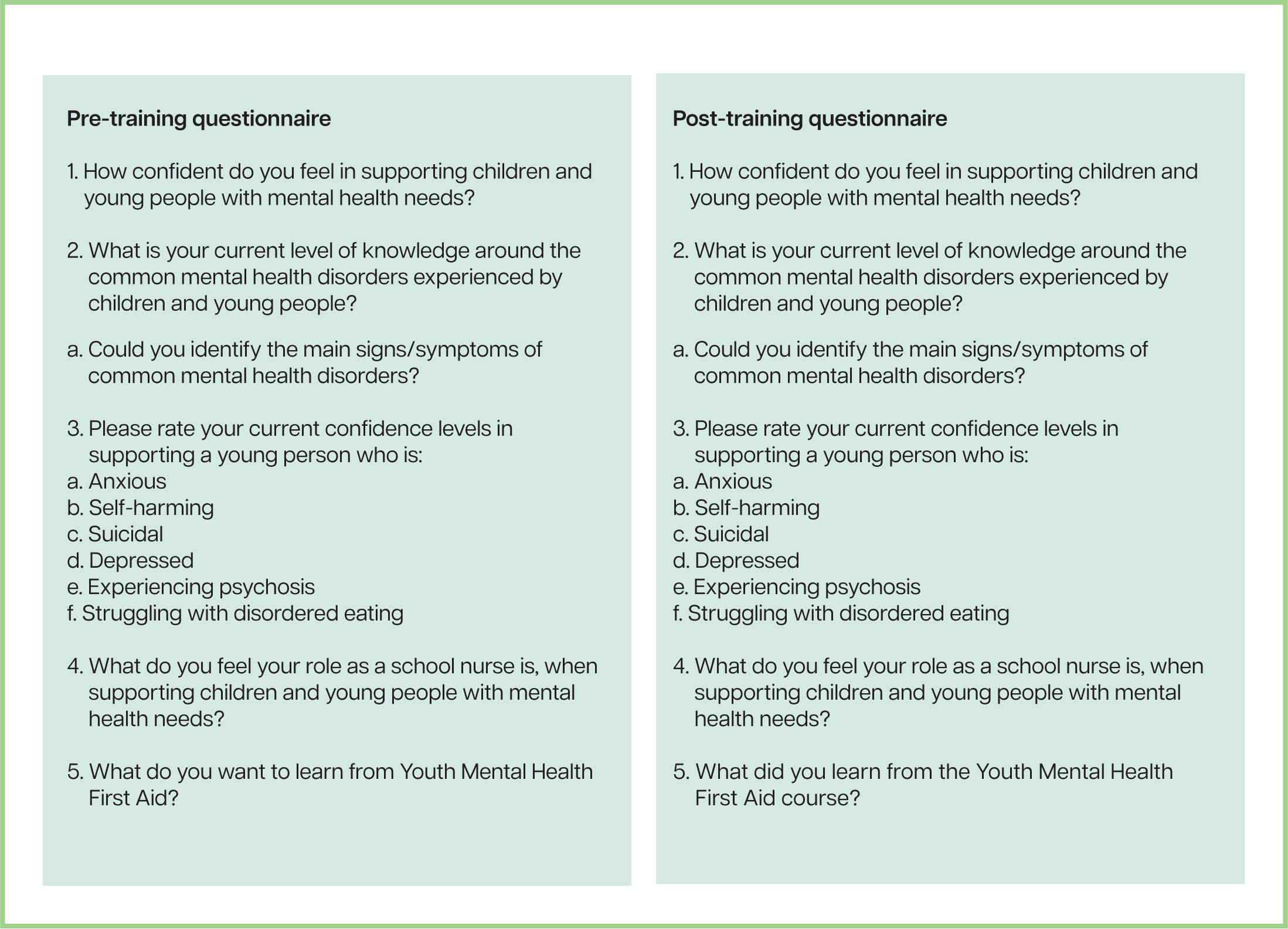

The surveys were formulated with five questions, relating to school nurses' confidence and knowledge around supporting children and young people with mental health needs, and school nurses' understanding their role when working with young people requiring mental health support. Both ‘pre’ and ‘post’ questionnaires retained the same questions for consistency. See Figure 1 for a copy of the questionnaires.

Procedures

Permission was sought from MHFA England to audit the effectiveness of the training for school nurses. This was granted, with the only stipulation being that the results were shared with MHFA England once published. An audit proposal for ethical approval was completed and submitted to the CLCHT Clinical Effectiveness group, in compliance with organisational guidelines. Participants were under no obligation to complete the questionnaires and were made aware that the data collected would be fully anonymised and the findings would be disseminated and considered for publication. For further ethical assurance, the proposal and ongoing study was also discussed as a standing agenda item in the ‘Time to Shine Project’ Safeguarding Working Group. The Time to Shine Strategic Group also had oversight.

| Variable | Mean score | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | Post-training | |

| Nurse confidence | 4.9 | 8.2 |

| Nurse knowledge | 5.6 | 8.4 |

Following ethical approval of the project, the proposed questionnaires were submitted to the Time to Shine, Safeguarding Working Group for feedback on fidelity to the overall aims of the QIP. The questionnaire was, subsequently, piloted during two Youth MHFA courses to ensure feasibility. Adjustments were made to the formatting of the questionnaire based on feedback to ensure clarity and to increase response rate. Questionnaires were then collected by the two instructors delivering the course, and data extracted manually. The paper copies of the questionnaire were then destroyed once the data had been anonymously digitised.

| Self-rated confidence | Response (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | Post-training | |

| Yes | 27 | 94 |

| Somewhat | 67 | 6 |

| No | 6 | 0 |

| Mental health presentation | Response (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | Post-training | ||

| Anxiety | Not confident | 20 | 0 |

| Somewhat confident | 65 | 25 | |

| Confident | 15 | 75 | |

| Self-harm | Not confident | 30 | 0 |

| Somewhat confident | 60 | 20 | |

| Confident | 10 | 80 | |

| Eating disorders | Not confident | 30 | 5 |

| Somewhat confident | 70 | 40 | |

| Confident | 0 | 55 | |

| Suicidality | Not confident | 40 | 0 |

| Somewhat confident | 60 | 30 | |

| Confident | 0 | 70 | |

| Psychosis | Not confident | 63 | 0 |

| Somewhat confident | 29 | 46 | |

| Confident | 8 | 54 | |

| Depression | Not confident | 9 | 0 |

| Somewhat confident | 86 | 27 | |

| Confident | 5 | 73 | |

Findings

The response rate for this audit was 55%. All questionnaires returned were included in the study, as missing data was minimal. Findings are summarised below in three key areas:

Nurse confidence and knowledge

Findings suggest that confidence and knowledge improved following completion of the course. All participants reported an improvement in their knowledge of mental health issues and their confidence in working with young people with mental health needs. The mean score in confidence levels increased from 4.9 pre-course, to 8.2, demonstrating a substantial increase. Moreover, participants' knowledge of mental health disorders also increased (from M=5.6 pre course to M=8.4). Prior to the 2-day course, only 27% of school nurses felt they could identify the overall signs and symptoms of common mental health disorders. Following the training, this had increased to 94%.

In relation to school nurses supporting children and young people with specific mental health needs, 95% of participants noted that they were either ‘somewhat confident’ or ‘confident’ in all of the identified areas after the training. This compares to only 25% of respondents self-rating as ‘somewhat confident’ or ‘confident’ before the course. After completion of the course, not a single respondent reported ‘no confidence’ in five of the six areas studied. These findings demonstrate a successful impact of a short (2-day) and cost-effective training, with resultant increases in clinician knowledge and confidence that is highly relevant and applicable to future practice. This finding is corroborated with a randomised controlled trial, which found that training school nurses on symptoms of depression was associated with significant improvements in understanding and recognising it (Haddad, 2018).

Previous research has demonstrated that 46% of school nurses received no additional training on supporting pupils with mental health conditions (Haddad, 2010) and low confidence rates reported of school nurses in relation to mental wellbeing (Pryjmachuk, 2011). The increased confidence levels and knowledge following from the 2-day Youth MHFA training package in this instance demonstrates promising outcomes for school nurses' ability to support the children and young people they work with.

Understanding of specific mental health conditions

Findings demonstrate that, for all categories of mental health presentation, nurses' confidence increased after completion of the Youth MHFA course. For all mental health presentations apart from ‘eating disorders’, no respondents reported ‘not confident’ after completing training. For anxiety, self-harm, suicidality, psychosis, and depression 100% of respondents were ‘somewhat confident’ or ‘confident’ after the course. The increased levels of confidence amongst the respondents was particularly high in relation to supporting a young person at risk of suicide. Prior to the course, no school nurses responded as being ‘confident’ in supporting CYP who were suicidal. After the training, 70% of school nurses reported feeling ‘confident’ in supporting a young person at risk of suicide, with the remaining 30% feeling ‘somewhat confident’. Thus, 100% of school nurses following from the training course report feeling capable of supporting a suicidal young person. Many respondents showed improved levels of confidence in supporting children and young people with eating disorders, with 55% noted they considered themselves ‘confident’ in this area now. This was the only category where non-confidence was reported after training completion (one participant) although a majority did show an improvement.

There was a significant increase in confidence and knowledge levels across all disorders and presentations, with suicide and self-harming showing the biggest increase. These findings demonstrate a positive effect of course attendance across a broad range of mental health presentations, which is further evidence of the Youth MHFA's wide-ranging applicability to school nursing practice. A 2011 review of school nurses and the developing roles around mental wellbeing noted that school nurses' low confidence levels are particularly around self-harm. The result from this audit demonstrates that delivering this 2-day course allows confidence levels to increase among school nurses, particularly when supporting children where there is an acute risk of physical, as well as ongoing, emotional harm (Pryjmachuk, 2011).

The role of the school nurse

Four themes were identified from the qualitative responses relating to the understanding of the role of school nurses in supporting children and young people with mental health needs (see Table 4). Across all themes there was a notable shift in perspective after completion of the Youth MHFA training course. All school nurses noted they regularly encounter pupils with mental health needs and clearly thought it was an important part of their role. However, prior to the course, nurses viewed their primary role as referring or signposting to other services. The majority of respondents, prior to course attendance, felt that referring to onward services was their main role and, therefore, nurse-led intervention and support for young people with mental health needs was not considered as part of their routine clinical input. Post-course, respondents retained an awareness for the requirement of specialist input and onward referral when clinically indicated. However, fewer respondents noted referrals as their only role following course completion. Some school nurses reported the need for referring a young person to specialist services only ‘if required’, which shows a shift in the thinking that supporting children with mental health needs is solely the responsibility of other practitioners. The Royal College of Nursing (2014) noted that it is not CAMHS sole responsibility to improve the emotional health of children and young people. Moreover, Young Minds recently noted that CAMHS referrals thresholds are high, but expanding the knowledge of the existing workforce across all healthcare professionals, is vital to supporting children and young people.

| Theme | Example pre-training | Example post-training |

|---|---|---|

| Early identification of MH needs | ‘We are usually the first person the young person comes in contact with and then we usually refer to other services’ | ‘School nurse could assess the child and identify any traits for the mental health illness’ |

| Referral or signposting onwards | ‘First line advice/referral’ |

‘Offering non-judgmental support. Seek more professionals input if required’ |

| Non-judgmental listening | ‘Listening, supporting, advice, signposting/referring’ |

‘Being that “someone” who can listen. Signpost for assessments and keep developing their coping strategies’ |

| Nurse-led intervention | ‘To be there to support and advise but not take on the main role for their mental health’ |

‘Someone that a young person could safely open up to with regards to their personal issues without any judgement, and someone who could give professional advice and proper management’ |

As well as increasing the CAMHS workforce, the ability to identify and support children with mental health needs is the responsibility of all healthcare professionals (Young Minds, 2023a). The findings from this audit show that respondents felt equipped with the knowledge and confidence acquired in the Youth MHFA training, which could be utilised to support young people with mental health needs in a variety of ways without solely relying on onwards referrals to already overstretched services unless necessary. These were ‘early identification of need’, ‘non-judgemental listening skills’, ‘nurse-led interventions’, and ‘risk assessment’.

Responses post-course highlighted an increased awareness of non-judgmental listening and nurseled intervention. The Youth MHFA pneumonic of ‘ALGEE’ as taught within the course, includes ‘listening non-judgmentally’ as a key aspect of supporting a young person, and the 2-day training course includes group activities for participants to practise active and non-judgmental listening. The importance of this is shown in the findings, see Table 4, as more school nurses see this as a key part of their role when working with children and young people. School nurses make up the biggest workforce in relation to public health support for children and young people, thus the importance of this workforce being non-judgmental, approachable, and supportive cannot be over-emphasised (Department of Health and Public Health England, 2014).

The results from this audit demonstrate the improvement in awareness of these skills for school nurses, which may prove vital to supporting the wellbeing of children and young people. In addition, Haddad and Tylee (2013) found that school nurses who demonstrated more understanding attitudes to mental health difficulties, were better at identifying mental health concerns amongst children and young people. This is a key finding to support the effectiveness of Youth MHFA training for school nurses.

It is also important to note that the increase in willingness to provide nurse-led interventions was also a theme from this audit. The responses did not contain much detail on the type or specificity of these interventions, but there are a variety of supportive emotional management techniques taught throughout the 2-day Youth MHFA course which the respondents may be alluding to. This is of importance in reference to the Young Minds recommendation of more healthcare professionals being able to provide interventions, rather than solely relying on CAMHS services (Young Minds, 2023b). Further research would be needed to elucidate this for school nurses and assess the types and efficacy of those interventions delivered. Nevertheless, this finding does note the importance of empowering school nurses to support children and young people with mental health needs.

Conclusions

Overall, this audit, as part of the Time to Shine QIP has demonstrated that completion of the 2-day Youth Mental Health First Aid course increased school nurses' knowledge and confidence in working with young people presenting with a wide variety of mental health needs.

School nurses were empowered to support children and young people who may be very mentally unwell, suicidal or self-harming, and confident in knowing when and how to refer to other services. Of note, support to a young person at risk of suicide saw the biggest increase in levels of confidence and improved understanding among the school nurses after course completion. This is a significant finding from the QIP. Moreover, completion of the course widened the scope and understanding of the school nurse role in supporting children and young people with mental health needs.

Thus, the 2-day Youth MHFA training in CLCHT is an effective training that can improve school nursing practice with the potential for wide-ranging impact on children and young people.