Around 96% of deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) children are born to hearing parents who have limited knowledge about deafness and Deaf culture (Moores, 2001). Deaf children who are born into hearing families and cannot make themselves understood are four times more likely to be affected by mental health problems than those with effective communication (Fellinger et al, 2009). Hearing families with DHH children receive limited information about the best routes for supporting a DHH child's language development, because of a lack of awareness in health professionals that families meet in their child's early years (Humphries et al, 2012). Research suggests there are difficulties identifying DHH children's emotional wellbeing issues compared to hearing children's, which can be a result of the variety of assessment tools used and limited generalisability (Barker et al, 2009; Vogel-Walcutt et al, 2011), with conflicting reports depending whose views are sought (for example, families' or teachers' views) (Van Eldik et al, 2004). Research studies of DHH children's mental health experiences are generally under-reported.

Deaf children's language and communication skills are often less well developed than those in hearing children, with language delays affecting development of neurolinguistic structures in the brain (if not achieved in the first five years of life) (Hall, 2017). Mayberry et al (2011) refer to this as the age of acquisition, meaning that if spoken language is not accessible for a DHH child, and sign language is delayed, it is likely that the window for learning closes and young DHH children will be disadvantaged. Language development impacts on understanding about feelings, emotions, behaviour and our relationship with others and the world around us. Emotional regulation, learning coping strategies, understanding others and ourselves are all factors that promote positive mental health (World Health Organization, 2019a; Orpana et al, 2016). Deafness is not by itself a risk factor for behavioural difficulties or mental health problems, but being DHH can be a risk factor because of the low language competence present for many DHH children (Stevenson et al, 2010). Deaf children and young people are consequently at higher risk of developing mental health problems than their peers.

The aim of this article is to examine opportunities that exist for DHH children to improve their knowledge and understanding of mental health and report the lack of evidence for mental health interventions available to improve young DHH people's mental health. This article does not focus on support or assessments provided by services or workers, but on tailored or specific interventions. The importance of researchers undertaking projects and sharing findings in this area is highlighted.

Background

Over 5% of the world's population experience disabling hearing loss, which will affect one in ten people by 2050 (World Health Organization, 2019b). According to the World Federation of the Deaf (2016), a lack of or loss of hearing is not always seen as a disability or a limitation, but more as part of a unique cultural and linguistic group. Having a strong Deaf identity can have a positive impact on a person's wellbeing. However, according to Fellinger et al (2012), limited availability of healthcare, variations in access to education, societal attitudes to DHH people and reduced opportunities regarding work and leisure often result in DHH people experiencing inequalities and not sharing a similar status to hearing people. If a DHH person experiences high levels of discrimination, feels marginalised and has low self-esteem, they are likely to have lower levels of psychological wellbeing than the general population (Briffa et al, 2016). Hearing populations have little knowledge of the challenges that Deaf people experience in everyday activities.

Having a strong Deaf identity can positively affect someone who is deaf or hard of hearing, but problems accessing healthcare, education and work can result in low self esteem, marginalisation and lower psychological wellbeing

Having a strong Deaf identity can positively affect someone who is deaf or hard of hearing, but problems accessing healthcare, education and work can result in low self esteem, marginalisation and lower psychological wellbeing

Around 40% of DHH people are likely to experience mental health problems during their lifetime, twice that of hearing people (Black and Glickman, 2006; Kushalnagar et al, 2019). The high incidence of mental health problems in DHH populations is likely because of communication barriers in a predominantly hearing world, adverse experiences related to stigma and discrimination, and the inability of current mental health systems to meet the specific needs of DHH people (Fellinger et al, 2009; Kvam et al, 2007). The reasons why DHH people experience more mental health problems than the general population largely relates to early life struggles with isolation, language delay, subsequent bullying, limited employment opportunities, and low self-esteem (Clegg et al, 2005). The National Deaf Children's Society (2020) report the prevalence of emotional wellbeing difficulties in Deaf children and young people as between 11% and 63%, with the range explained by differences in report measures. According to Wright (2020a), 26% of a sample of 144 signing deaf children and young people in England not currently accessing child mental health services had a probable mental health problem and 57% had a possible mental health problem.

Mental health screening tools used for hearing young people may underestimate or overestimate the incidence of mental health problems in DHH youth because of differences in language and expression (Dreyzehner and Goldberg, 2019). On a more positive note, availability of health assessment tools translated into British Sign Language has increased (Roberts et al, 2015; Rogers, 2013; Rogers et al, 2016), which assist in the early identification of mental health difficulties. There has also been an increase in the development and delivery of tele-mental health services specifically available to DHH adult populations through video-conferencing formats (Wilson and Schild, 2014; Crowe, 2017; Pertz et al, 2018). In some areas, DHH services are provided by qualified Deaf people. However, even with good outcomes from Deaf mental health specialists, there is a shortage in their availability, which is a further barrier to mental health provision for many DHH individuals (Crowe et al, 2016).

According to the National Deaf Children's Society (2020), few studies are reported that assess the effectiveness of interventions delivered directly to DHH young people to improve emotional wellbeing (although they acknowledge that family support and social skills development play an important part). Currently, DHH young people who require input from mental health services may be referred to a national Deaf Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) (Wright et al, 2012; Sessa and Sutherland, 2013). However, the likelihood is that few DHH children ever access support from a specialist mental health service, with most likely to be supported by education or third sector provision, where staff may have specialist knowledge about deafness but not about mental health (Wright, 2020b).

Many programs exist that support hearing children's positive mental health, although few have been evaluated. Interventions can include whole community approaches, targeted youth campaigns, school-based mental health interventions and programs that support crisis intervention by individuals (Kelly et al, 2007). Mental health promotion interventions specifically for young people in low-and middle-income countries have reportedly shown that school-based life skills and resilience programs received moderate quality ratings, with positive effects reported on students' self-esteem, motivation and self-efficacy (Barry et al, 2013). Approaches need to be tailored to specific young people audiences to address needs and preferences and ensure relevance. Programs also need a theoretical health promotion base, appropriately evaluated to gauge success in behavioural change (Kelly et al, 2007).

Mental health literacy is defined as understanding how to maintain positive mental health, understanding mental disorders and their treatments, decreasing related stigma and knowing when and where to seek help, and developing competencies designed to improve mental health care (Kutcher et al, 2016). Yet despite the risks of increased mental health problems in DHH communities, evidence of what works to improve mental health for DHH children and young people is under-reported, and this review set out to establish the published evidence.

Methods

Search strategy

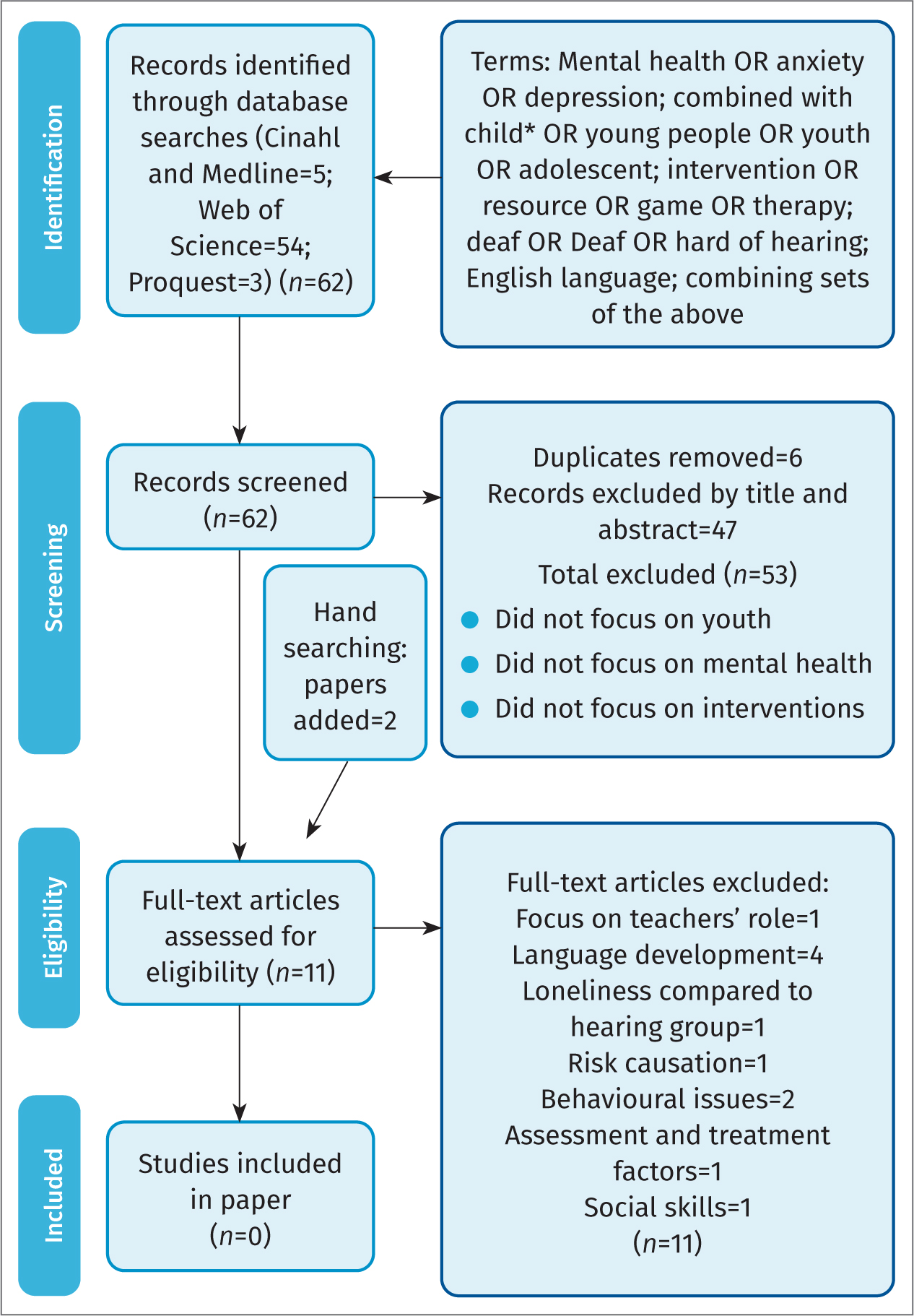

A literature search was undertaken between September and November 2020 of CINAHL, Medline, Web of Science and Proquest for peer-reviewed articles. A search string was developed to include the search terms, which are displayed in Figure 1. The PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study design and setting) framework was used, as shown in Table 1, to identify evidence, as it assists a comprehensive search (Methley et al, 2014). Terms were used with Boolean operators to narrow results. No limitations on year of publication were applied. Reference lists were inspected for other appropriate studies to determine if material had been overlooked.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram

Table 1. PICOS framework

| PICOS component | Search terms (BOOLEAN operator OR) |

|---|---|

| Population | Child* OR young OR youth OR adolescentDeaf or deaf or hard of hearing or d/hh |

| Intervention | Intervention* OR resource* OR game* OR therap* Mental health OR anxiety OR depression OR self-esteem |

| Comparison | N/A |

| Outcomes | No parameters |

| Study design and setting | (Any design, any country) |

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- Peer-reviewed

- Written in the English language

- Focus on an intervention to improve young Deaf people's mental health

- Primary research, opinion pieces, case studies.

Papers were excluded if they were non-peer reviewed material, in languages other than English, and if the main research study did not focus on young Deaf people and an intervention to promote mental health, to prevent mental health problems or to support mental health in some form.

The anticipation was that mental health literacy packages frequently delivered to hearing young people would also be available to DHH young people. The intention was to note the nature of interventions or activities (group, face-to-face, one-to-one, content, location) and materials, devices, and workers involved.

Results

Initially, 62 articles were retrieved, with six duplicates subsequently removed. The remaining 56 papers were scanned by title and abstract for relevance, with 47 removed as the focus of the paper was not on young DHH people and mental health. The full text of the remaining nine papers was examined (Figure 1). Reference lists and grey literature were hand searched, and a Google Scholar search was conducted, adding two further papers. All 11 papers were excluded, as the focus was not on an intervention with young DHH people relating to mental health, meaning no studies were identified as suitable for review. The search process (Figure 2) used PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) guidelines (Moher, 2009).

Discussion

It is significant that there is a lack of evidence on interventions that promote positive mental health for young DHH people. Literature reviews are useful for establishing potential proposals for future experimental research and to guide policy and practice until additional research can examine the effectiveness of new programs and practice. Opportunities exist for researchers to work closely with DHH communities and organisations to develop and evaluate culturally specific relevant mental health literacy programs for an at-risk group. The majority of literature about DHH youth focuses on language development and acknowledges that emotional and behavioural difficulties are prevalent in DHH children, linked to language ability, particularly receptive knowledge (including understanding others, how to interpret the world), as well as how to share and regulate emotions. It is perhaps unsurprising that there is overlap between social, emotional and behavioural intervention research with DHH young people, but not specifically framed in the context of supporting positive mental health in the longer term. According to Luckner and Movahedazarhouligh (2019), as there is a paucity of research on social–emotional development and learning with DHH young people, there is little guidance available to support caregivers and educators, which is frustrating for families, educators and early interventionists. Services that support children's development often operate separately, meaning that those in education may have limited interface with workers in children's or mental health services. Stevenson et al (2010) identified that supporting language and literacy development in DHH and hard of hearing populations may additionally benefit individuals' mental health, but without longitudinal studies, outcomes of interventions would remain unknown.

According to Bigler et al (2018), 20% of young people in the general population have disruptive behaviour problems, which increases their risk of engaging in substance misuse and criminal behaviour. It is concerning that around 50% of Deaf young people are likely to have behavioural problems (Hindley and Kitson, 2000) and are consequently much more at risk of activities that would increase their vulnerabilities further. Despite the increased risk of behavioural problems that may well lead to mental health issues, Bigler et al (2018) draw attention to a significant gap in evidence about the development of behavioural problems for DHH children. Evidence is available that shows efficacy and effectiveness for training programs with parents of hearing children (Stormshak et al, 2000; Webster-Stratton et al, 2011). As DHH children's behavioural problems reportedly relate more to language development than to hearing problems specifically (Stevenson et al, 2010; 2011), it may be wise for practitioners and researchers to examine links between language and understanding feelings in the context of exploring DHH children's behaviour and the impact on their mental health too.

Notably, if attention is not given to DHH children's language development, the consequences can significantly impact on individuals, families, and communities. Bigler et al's (2018) review of assessment and treatment of behavioural disorders in children with hearing loss identified that children with disruptive behaviour often experience internalising symptoms like anxiety and depression, which can go undetected. If untreated, disrupted behaviour can lead to a ten-fold increase in costs for education, health, and criminal justice into early adulthood (Reinke et al, 2012). The potential risk for DHH children being part of the criminal justice system is much higher than for hearing children because of cognitive, linguistic, and social challenges (O'Rourke et al, 2013).

Commonly, health and development risks are not known to families with DHH individuals. Screening measures used to assess DHH young people's mental health issues such as anxiety and depression often fall short as they do not take account of language acquisition and expression, and it has been suggested that 26% of DHH young people meet the criteria for clinical depression (Dreyzehner and Goldberg, 2019).

As DHH people experience social marginalisation and inequalities of access to information, there is a higher risk of inadequate health literacy. McKee et al (2015) found DHH people were nearly seven times more likely to have poor health literacy compared to hearing people. Disadvantages like poor health literacy are certainly one of the reasons why DHH people's mental health problems are twice that of the hearing population (Smith et al, 2012). Naseribooriabadi et al (2017) suggests that further training for health professionals about effective communication with DHH patients, increased quality of sign language interpreter provision, and the development of DHH-tailored educational health programs and materials would certainly help. According to Pollard and Barnett (2009a), even highly educated DHH adults demonstrate a risk of low health literacy, with the general DHH population at even higher risk for health problems associated with lower health literacy.

The field of digital technology may offer some solutions to improve DHH people's mental healthcare experiences. Digital health is concerned with the development and use of technology that aims to improve health and wellbeing, and may include wearable gadgets, sensors, mobile apps, electronic records, and interactive online resources. Digital health technologies can improve access to health systems, reduce costs, improve quality of care, and encourage people to better manage their own health (World Health Organization, 2019b). Notably, digital technologies can help reduce health inequalities by offering services remotely, and promoting health literacy and better access to support networks and health systems, which are all areas that would potentially improve DHH people's mental health. Researchers, policy makers and practitioners may be assisted by evidence standards frameworks that describe the evidence and value of digital health technologies (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2019). Digital health technologies included might focus on information, behavioural prevention, systems, self-management, monitoring and diagnosis. To date, the efficacy and availability of digital mental health technology to support DHH people is under reported.

Naslund et al (2019) point out that individuals are more likely to have access to a mobile device than to mental health services, which does support the development of further digital mental health support, but with the caveat that end user engagement in the design of such digital interventions is essential. Deaf or hard-of-hearing children can experience difficulties in learning health principles, but Abbasi (2017) states that technology has significantly improved DHH young people's ability to learn more and tested this by trialing a health education mobile application. Deaf communities were initially reported to have less access to ICT resources than hearing people because of income and educational disadvantage, but access now seems to be more equal (Singleton et al, 2019). The internet is enabling DHH users to access a broad range of information, which in turn increases ability and opportunity to engage with the hearing world, so DHH people are now more connected to public and political matters and can participate more democratically than previously. Deaf people have been reported as significantly more likely to use the internet than the general population to look for health information (65% versus 27%) (Valentine and Skelton, 2009; Karras and Rintamaki, 2011). However, web-based information is seldom accessible in DHH-friendly or signed language formats. Smith et al (2012) stress the importance for interdisciplinary professionals to investigate the health interests and health information-seeking behaviours of DHH communities.

A variety of digital technology formats are worth further exploration for health literacy information. For example, sports-sign web-based applications have been developed to relay sports news in sign languages using the technology of avatar (Uchida et al, 2019), which implies technology is certainly available to share health information to wider audiences in accessible formats.

Vis et al (2018) found that many electronic or digital interventions available to support mental health currently focus on mood disorders like depression, and there is a need to better understand barriers and challenges that promote or prevent usage of digital supports. Equally, in their review of eMental health studies, Vis et al (2018) found 26 of 48 retrieved papers focused on video conferencing technologies, which suggests greater activity regarding the engagement of people via a platform rather than an actual digital or health literacy intervention, and none of the studies retrieved focused on DHH people.

Bevan-Jones et al (2020) stresses the increasing interest in digital technologies to improve young people's mental health has rising evidence, and examined co-design approaches, identifying 30 co-designed digital mental health technologies that included a range of gaming, avatars, interactive modules and videos. It is worth bearing in mind that it does not translate that what hearing young people find beneficial will work for DHH young people. According to Furness et al (2019), classroom teachers have little training on how to support DHH young people's mental health or access to relevant resources. Frequently, it is parents and education staff who are asked about DHH young people's performance, engagement and support needs rather than DHH young people being involved themselves (Khairuddin, 2019). Mental health interventions that promote understanding about feelings and the need to communicate will certainly help reduce the risk of depression in DHH young people (Dreyzehner and Goldberg, 2019). Communities, practitioners and researchers are aware of the increasing focus on young people's mental health, so it is surprising that so little is known about engagement with marginalised groups of children from under-served backgrounds (Bergin et al, 2020), whose mental health appears to be at great risk.

Limitations

Evidence reported about mental health and mental health interventions, particularly in youth populations, can be categorised using keywords including behaviour and emotions. Terms including ‘child behaviour’ were not included in the search strategy as these were considered too broad, yielding a high number of papers that were not the focus of this review. Equally, terms including phrases such as ‘mental health literacy’ and ‘mental health promotion’ were not used, nor were eHealth or mHealth technologies, as they were found to be too specific, yielding no results. The search criteria used should have been robust enough to detect relevant studies, but it is possible that small studies or evaluations were undetected.

Conclusions

Early reports about how to respond to DHH young people's mental health issues stress the need for work in the area of prevention, and a need for adequate knowledge and guidance with a focus on healthy living (Rainer and Altshuler, 1966). Health literacy in general needs to be adapted for DHH audiences so it is accessible, relevant, engaging, and effective (Pollard et al, 2009b), with mental health literacy interventions for DHH people warranting the development of further interventions and research (McKee et al, 2015). There is a role here for researchers to further develop both assistive technologies to enable greater engagement in a hearing world, as well as digital interventions that seek to improve young DHH people's mental health literacy, but only with full engagement from young DHH people themselves.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- In your current role, what are the main factors that do support and promote young d/Deaf people's mental health?

- How do hearing children experience mental health interventions in different settings? Think whether these would be suitable for d/Deaf young people – why/why not?

- Where do you go to for information and support about young d/Deaf people's mental health? (people, places, websites, organisations, etc)