Digital mental health tools offer online programmes to improve mental health, often targeting specific psychological conditions. SilverCloud® by Amwell® is a platform providing a variety of digital mental health programmes, and has recently been conditionally recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2023) as an initial treatment option for children and young people, as part of their early value assessment.

The SilverCloud platform offers online programmes tailored to specific mental health diagnoses. These programmes are structured into modules of content, including interactive exercises, video resources and options for journaling and online reflection. This content is rooted in evidence-based models, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which is recommended for the treatment of mild to moderate mental health disorders (NICE, 2011), among other therapeutic approaches. Users can engage with the programme independently, and the setup aims to provide them with a personal space for self-reflection and introspection.

As well as programmes designed for adults, the SilverCloud platform provides programmes designed for teenagers aged 15 years and over. There are also programmes for parents and carers, aiming to empower parents to help their children overcome mental health challenges. These include parenting programmes for children (3–12 years old) and teenagers (13–18 years old) with anxiety and children (5–12 years old) with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Box 1) (Harty et al, 2023). Providing this support to families is crucial given the high rates of mental ill health among children and young people, with data from 2023 indicating that 20.3% of those aged 8–16 years are experiencing a probable mental health disorder (NHS Digital, 2023). The NHS has been struggling to keep up with demand for child and adolescent mental health care, leading to families facing long waits for care for conditions such as ADHD (ADHD UK, 2023). Digital interventions could provide an easily accessible means of support for children and young people with this condition and their families.

Supporting neurodivergent children and young people with their mental health

The ‘Supporting a Child with ADHD’ SilverCloud programme has been designed for parents and carers of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It is a neuro-affirming programme which recognises that ADHD is a developmental difference that comes with strengths as well as challenges. These challenges can be stressful and even disabling and can lead to an increased likelihood of mental health issues. Therefore, providing these children with specialised attention and treatment is crucial to their development and wellbeing.

Based on the Parents Plus (2024) ADHD Children's Programme, the SilverCloud ADHD programme teaches a range of practical strategies to help parents manage their child's ADHD, such as understanding the challenges of ADHD, problem solving and communication, positive behaviour management, building self-esteem and wellbeing, as well as supporting school, education and friendships. The focus is on helping parents to look after their own needs as well as those of their children, and to help them create and maintain warm and connected family relationships.

Personal support

The NICE (2023) has emphasised the need for digital mental health programmes to be supported by healthcare professionals. Unlike many other digital mental health tools, the SilverCloud platform provides users with feedback from a dedicated online supporter as they progress through their online journey. As users navigate the programme, working on their learning and reflection on a weekly basis, the supporter, a professional in the field, actively engages with them, offering encouraging feedback, highlighting accomplishments and guiding them to further resources.

A crucial distinction here is that this supporter must be a real person, not artificial intelligence. Research indicates that individuals tend to benefit most from therapeutic interventions when there is direct human interaction (Andersson and Titov, 2014). The personalised support provided as part of the SilverCloud programmes serves as a motivator, helping users to successfully complete the programme. Coupling a structured programme with personalised support significantly increases the likelihood of users persisting beyond initial stages, ensuring progress through the entire programme (Harty et al, 2023).

The healthcare professionals who fulfil the supporter roles are provided with the information required to support platform users, and the role is designed so that supporters do not need to have specialist expertise in CBT or extensive training in the entire therapeutic model. This opens the supporter role to a wide variety of healthcare professionals, from therapists and assistant psychologists in the mental health service, to volunteer counsellors and school nurses, so long as they have strong supportive skills and are familiar with the programme's structure.

All supporters receive training in the programme and are supervised by senior clinicians within the delivering service or the SilverCloud organisation, who monitor the quality of the work and make sure that risk and safety protocols are followed. For example, if a supporter identifies that a child using the service is in crisis, they are supported by a supervisor to protect the child and to manage their own wellbeing. The specific safety protocols are determined by the NHS service that has commissioned the SilverCloud tool.

It can be reasonably assumed that supporting a young person through a digital programme is less time consuming for healthcare professionals than providing an equivalent level of support through face-to-face sessions. The SilverCloud platform supporters operate within specified hours, such as Tuesday mornings. During these designated times, supporters can log in to the app, where they can access an online database of their clients and a structured schedule for managing their tasks. This structured approach is designed to help supporters to manage their workload efficiently, ensuring that they can provide support and offer feedback to all the accounts assigned to them during their scheduled times. This can allow trained therapists to support up to four times more children than face-to-face therapy alone (American Well Corporation, 2023).

Parental involvement

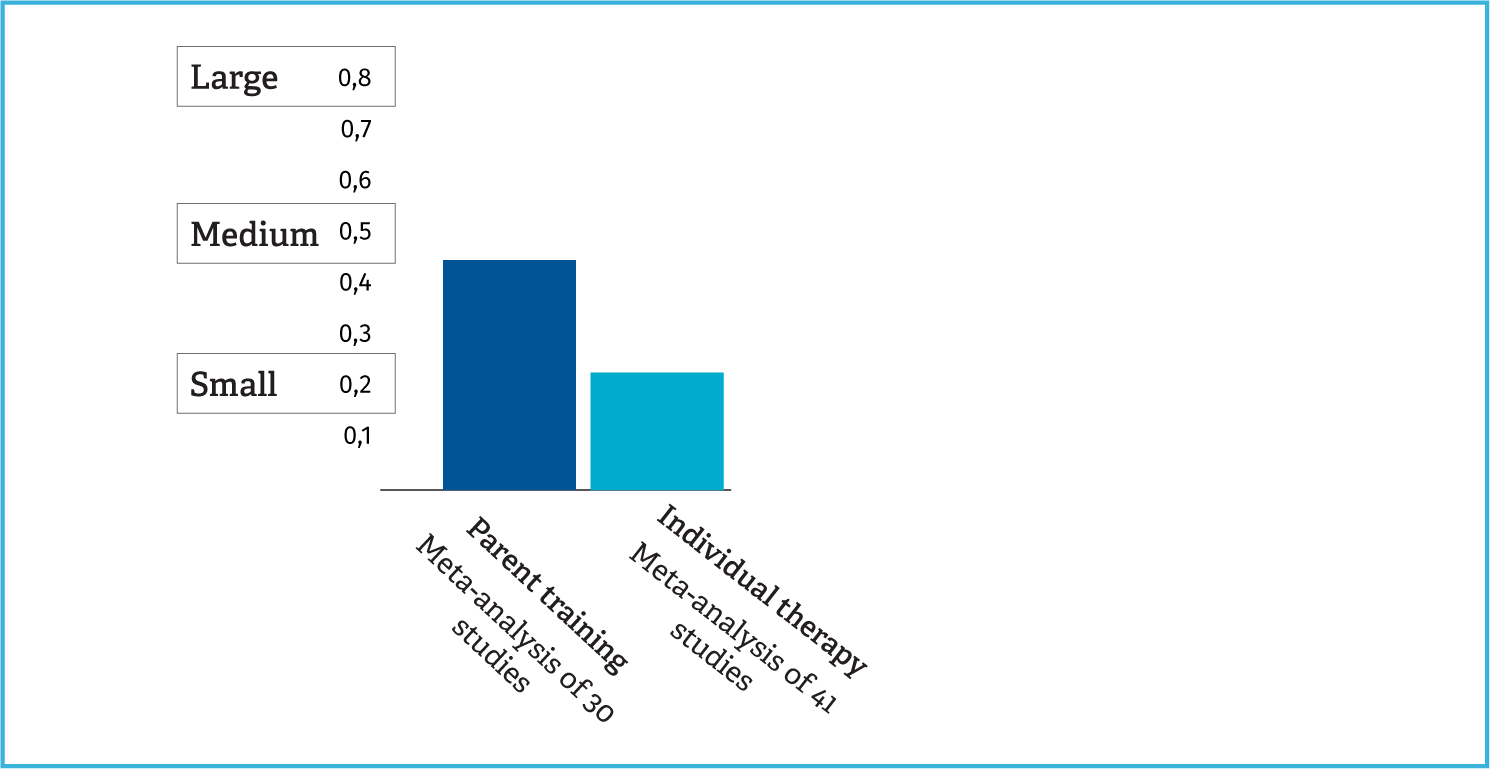

Research has shown that involving the patient's wider family, especially their parents, can be a more effective in achieving positive changes for the child (Creswell et al, 2020; Jewell et al, 2023). A meta-analysis by McCart et al (2006) found that CBT involving both teenagers and their parents was twice as effective as CBT involving teenagers alone (Figure 1).

‘Research has shown that involving the patient's wider family, especially their parents, can be a more effective in achieving positive changes for the child.’

This can be partly explained by the substantial influence that parents typically have over their children's lives. Parents are often a constant and consistent presence in their children's lives, spending more time with them than anyone else. A meta-analysis by McCart et al (2006) found that, for children with antisocial behavioural problems, interventions targeted at parents were more effective than those targeted at the child in terms of facilitating positive changes in the child's life. This effect is greater in younger children, but remains true among young teenagers, with parents continuing to play a crucial role in their children's lives, even as they grow older and more independent.

A child's mental health can be challenging for parents or carers to deal with, while parents may struggle with mental health challenges of their own that in turn impact their children (Harden, 2005). Therefore, a therapeutic approach that includes parents and children could have mutually reinforcing dual benefits within the family dynamic, as assisting one generation indirectly benefits the other. It is crucial to note that this approach does not mean solely working with parents instead of the child or young person, as engaging with both parties tends to yield more effective outcomes (McCart et al, 2006). This is why the SilverCloud programmes for anxiety and ADHD in children and teenagers have been designed to involve parents.

‘Programmes are offered directly to parents with the aim of empowering them to understand their children in a more compassionate and positive manner that is attuned to their needs.’

Parent-inclusive programmes

The SilverCloud platform's Anxiety and ADHD programmes are set up for the young person (aged at least 15 years) to access and engage with independently and in privacy. This privacy aspect is crucial, ensuring a safe space for the young person. Simultaneously, parents have the option to log on and participate in a separate parenting programme, with specialised content tailored for them. For children and younger teenagers, parents can download worksheets from the parenting programme to complete with their children. These worksheets provide exercises in problem-solving, anxiety analysis and step-by-step strategies to manage worries, and allow parents to engage with their children by working through these exercises together. This collaborative approach ensures that ideas and strategies from the parent's programme can be shared and applied to benefit children and young people.

Programmes are offered directly to parents with the aim of empowering them to understand their children in a more compassionate and positive manner that is attuned to their needs. This understanding may help parents to find constructive ways to manage challenging situations and make better choices in their responses. When a child exhibits signs of anxiety or depression, parents might respond with frustration or anger. The child's behaviour may disrupt family routines or events, causing distress for both the child and the parent. For instance, if a planned family outing is derailed because the child is having a panic attack, it not only affects the child but also impacts the parents' experience of family events. Similarly, if a child refuses to attend school because of struggles with ADHD or anxiety, it becomes a significant concern for parents who believe in the importance of their child's education. The SilverCloud programmes aim to help parents in these situations to better comprehend what their children are experiencing and, equally importantly, understand their own feelings with empathy. This can prompt them to pause, respond less reactively and so avoid negatively impacting the child's self-esteem. Ultimately, this approach aims to promote the child's success, happiness and the establishment of a family life that benefits both the children and the parents.

This dual programme structure is designed for mutual benefit, with the assumption that more individuals in the family unit engaging with the programme will lead to greater potential benefits for the whole family.

Consent

It is essential to work with whoever is willing and available to receive support. It is common for parents to be the initial point of contact with mental health services for young people. A child who is distressed is likely to be hesitant or unable to actively seek support, while a concerned parent may be better able and more willing to reach out.

In instances where parents who are concerned about their child's wellbeing seek help without the child's direct involvement, it is important to prioritise the child's comfort and consent in the therapeutic process. Focusing on working with the parent alone might be more impactful than pressuring the child into therapy against their wishes. In the author's experience, enhancing the parent's understanding, communication and support toward their child can significantly contribute to positive changes, whereas compelling children to attend counselling without their readiness or willingness to engage can be highly challenging and ineffective.

Many children and young people may not be emotionally prepared to discuss their struggles, nor wish to converse with someone unfamiliar. It is important to be mindful of the significant stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues, particularly for young people, and to respect their choices as to when and how they wish to engage. Providing programmes directly to concerned parents can be an effective alternative to pressuring an unwilling young person into therapy in the first instance.

Outreach

Creating awareness is key to improving the uptake and effective use of digital mental health tools among children and young people. This can involve both individual engagement from healthcare professionals and collective efforts from school authorities. For instance, schools aiming to bolster mental health could widely communicate about the availability of digital mental health tools, encouraging parents and students to reach out. These tools could also be mentioned during individual face-to-face discussions between young people and health professionals, such as through workshops on positive mental health or anxiety. Friendly outreach can help to normalise and validate the usefulness of digital mental health tools, presenting them in a way that helps potential users perceive them as genuine sources of therapeutic support.

It is essential that young people (and their parents) who may benefit from digital mental health platforms, such as those provided by SilverCloud, have an opportunity for one-to-one personal interactions with a healthcare professional beforehand. Merely offering the digital programme to young people without adequate explanation or preparation is unlikely to yield success. This contact can be digital or face-to-face, and it should be initiated with the method best suited to the recipient's comfort, considering their varying levels of distress. In some cases, a phone call may be preferable, while others may prefer an online welcomes or emails that offers assurance of human support without being overly rigid. This personal contact is crucial for building rapport, fostering personal relationships and ensuing clarity in the referral process, as well as enabling users to familiarise themselves with SilverCloud, grasp its potential benefit and raise any concerns they might have. Thus, professionals referring young people for SilverCloud need to fully comprehend the programme and be able to alleviate potential concerns. The referring person also has a crucial role in encouraging parental involvement, by introducing them to the programme and guiding them through it.

Overcoming barriers

In the author's view, the barriers to uptake and continued use of digital mental health tools often relate to how they are integrated with human involvement, with optimal effectiveness occurring when a person familiar with the programme refers the individual, offers guidance and initiates their participation. A well-structured referral network and initial guidance are crucial, followed by ongoing support and check-ins to ensure continued engagement. Some individuals can manage the entire process online, but this largely depends on their characteristics. For instance, in university settings where counselling services are available, the availability of the programme may simply be announced, and individuals with high levels of digital literacy may readily engage online. However, it is essential to provide additional support to guide and motivate them throughout the programme.

Obstacles and opportunities to accessing digital mental health tools are often specific to the setting where these tools are to be implemented. Identifying and analysing potential context-specific barriers can be crucial to devising effective strategies to overcome them. For instance, in a school, a young person experiencing anxiety might engage with the school counsellor. In this scenario, the counsellor could introduce the programme with a personal touch, encouraging the young person to participate. The individual can then choose to involve their parents in the process or opt to keep their engagement private, which is acceptable as well. For younger children, the counsellor might initiate contact with the parents. Alternatively, the school could extend a programme's offering to all parents, allowing them to self-select based on their child's needs. This approach might enable some parents to identify and engage with the programme for children actively experiencing anxiety, while others may participate preventatively.

‘Parental involvement in these programmes can be a positive way to encourage positive changes for parents and children alike, so long as care is taken to protect the young person's consent and privacy.’

The NICE (2023) has stated that there is early evidence for the effectiveness of digital mental health programmes, such as those provided by SilverCloud, for children and young people with mild-to-moderate symptoms of anxiety or low mood. The NICE committee also acknowledged that many children and young people on waiting lists for mental health care will have no access to support or clinical risk monitoring. Digital mental health platforms could prevent progression to move severe mental illness among these individuals (NICE, 2023). However, further research is needed to evaluate the impact of these interventions on children and young people, and to identify and overcome any barriers to access.

Conclusions

Digital mental health tools such as SilverCloud could be an accessible and effective way to support young people with mental health diagnoses, including anxiety and ADHD. Parental involvement in these programmes can be a positive way to encourage positive changes for parents and children alike, so long as care is taken to protect the young person's consent and privacy. Proactive outreach and personal contact can overcome barriers, improve uptake and encourage engagement with these tools.