Fever in children under 5 years of age is a common presenting problem for parents, and one of the most frequent reasons why they seek medical attention (Barbi et al, 2017). It can affect 70% of preschool-aged children, leading to a substantial amount of parents or carers seeking medical care (Hussain et al, 2020; Sakr et al, 2022). Although it is common in this age group, it rarely indicates a serious illness (Sakr et al, 2022). Education about fever is, therefore, an important issue for all health professionals supporting parents and carers of children under 5.

A fever is a physiological defence mechanism characterised by an elevation of body temperature above the normal range (Whitburn et al, 2011). It is defined by a rectal temperature of ≥38 °C or by axillary temperatures of ≥37.5 °C (Ogoina, 2011; Whitburn et al, 2011).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2023) defines fever as ‘an elevation of body temperature above the normal daily variation’, which is thought to be 38°C or higher. It can be a standalone symptom or associated with other symptoms, such as a lymphadenopathy, cold-like symptoms, skin rashes or any other organ system involvement (Jayashree et al, 2024). Although seen as a defence response, a systematic review by Milani et al (2024) showed that fever can also cause discomfort, mental distress, reduced appetite and disruptions in sleep patterns.

Generally, the most common cause of fever is a self-limited viral infection (Antoon et al, 2015). Globally, the most common causes of fever are respiratory infections in 60% of cases and gastrointestinal illness in 16% of cases (Jayashree et al, 2024). Children can, however, occasionally present with a fever of unknown origin (FUO) where they can have a temperature of 38°C or higher that cannot be explained with associated inpatient or outpatient evaluation (Antoon et al, 2015). Therefore, it is important to identify the cause in case this needs to be treated.

Assessment

Parents may report their child as feeling hot to touch and this should be considered as important as objective data (NICE, 2021). A temperature reading is an objective measurement and can be taken in the axilla, rectum, mouth, skin, and ear. There are substantial differences among measurement sites. Rectal thermometers are considered the most accurate but are not recommended as standard practice (American Academy of Paediatrics, 2012; Allegaert et al, 2014). Less invasive tools to assess temperature are recommended in the UK, although some healthcare systems still favour rectal thermometers (American Academy of Paediatrics, 2012; NICE, 2021). The suggestion is that the variation is so small it is not worth using an invasive assessment tool (Craig et al, 2002). Teller et al (2019) suggest, however, that axillary readings can be used for screening, but critical measurements should be confirmed by more reliable methods.

NICE guidelines

Measurement of the body temperature of infants under the age of 4 weeks should be taken with an electronic thermometer in the axilla (NICE, 2021).

In children aged 4 weeks to 5 years, body temperature should be measured by one of the following methods (NICE, 2021):

Fever can be a symptom of an underpinning disease. There are signs and symptoms that can be reviewed which are suggestive of specific diseases. One example is Kawasaki disease where patients may present with fever for 5 days or longer and may have some of the following (NICE, 2021):

It is important to take a systematic history to determine that there are no other associated signs and symptoms that are significant, or indicators of underlying disease (Connolly and Eppes, 2014).

The NICE 2021 and 2023 guidelines for fever assessment in children under the age of 5 years provide clear direction as to the assessment and management. These are also being implemented in other healthcare systems supporting and improving patient outcomes (Isa et al, 2024).

NICE (2023) suggests that the following need to be considered during history taking:

Management

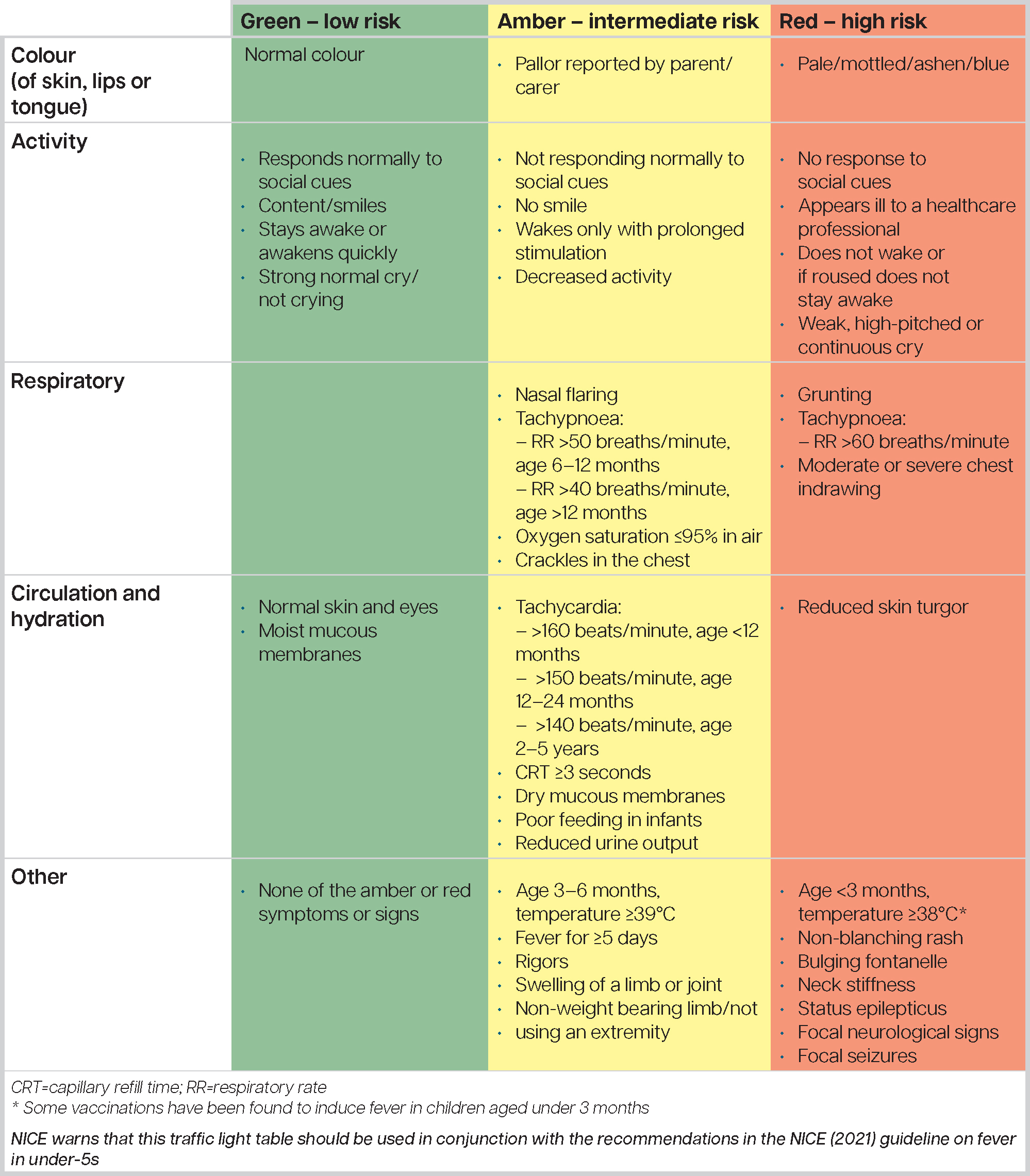

The first step of management of fever is to identify any immediately life-threatening features, including compromise of the airway, breathing or circulation, and decreased level of consciousness as in suspected sepsis (NICE, 2019). This can be done using the traffic light system outlined in Figure 1, used in conjunction with the recommendations from the NICE (2021) guideline.

National and international guidelines differ in the management of fever (Green et al, 2021). Many healthcare providers and parents view fever as a dangerous condition or a discomfort to be eliminated, despite evidence that fever is a defence mechanism against acute infections (Purssell and Collin, 2016). Certainly, parental concerns and ‘fever fear’ or ‘fever phobia’ have been well documented and have arisen due to the belief that fever is a disease rather than a symptom or sign of illness (Schmitt, 1980; Sakr et al, 2019; Villarejo-Rodríguez et al, 2019; Crocetti et al, 2021). As a response to this fear, parents often unnecessarily overtreat fever or seek emergency advice (Çelik and Güzel, 2024).

Lynch et al (2024) suggest that empowering caregivers with the knowledge to safely and manage fever at home has the potential to reduce parental anxiety and associated demands upon healthcare services. Milani et al (2024) highlight the prevalence of ‘fever phobia’ among caregivers and healthcare providers, which can lead to inappropriate interventions. Lynch et al (2024) suggest that brief educational interventions can rapidly increase caregiver knowledge about fever in children and reduce parental anxiety.

Thompson et al (2020) found in their systematic review that parents worry about the implication of childhood fever and often lack key information upon which to base their caregiving and decision-making. They generally want information and reassurance during the episodes of childhood fever. There is certainly a need to provide clear, easily accessible information about fever for caregivers and healthcare providers. Chiaretti et al's (2024) cross-sectional, web-based survey in Italy to investigate the current management of fever and associated symptoms in different settings, including primary and secondary care found that paracetamol was the most prescribed drug to treat fever in adults and children. Valenzise et al (2024) suggest that paracetamol is the antipyretic of choice due to its ease of handling and effectiveness. In the UK, paracetamol is considered the first-line antipyretic (Green et al, 2021; NICE, 2021). Although paracetamol is the preferred choice of antipyretic, ibuprofen has also been shown to be effective in lowering temperature (de Martino et al, 2017; Green et al, 2021).

NICE (2021) recommends only using paracetamol or ibuprofen in children with fever for as long as the child appears distressed. Carers should consider changing to the other agent if the child's distress is not alleviated and not give both agents simultaneously. They should only consider alternating agents if the distress persists or recurs before the next dose is due.

There is some debate about tepid sponging as, despite evidence that it increases discomfort in the child, some global guidelines still include it (Green et al, 2021). In fact, tepid sponging has not been recommended for the treatment of fever since 2007 (NICE, 2021). It is also advisable not to underdress or over-wrap children (NICE, 2023). The guidelines for parents are outlined in Box 1.

Advice for parents and carers (adapted from NICE, 2023)

Health professionals also need to ensure that parents and carers are provided with safety netting advice, which includes any further warning signs and symptoms of when to seek urgent medical advice. These should include (NICE, 2023):

The classic ‘red flag’ symptoms of meningococcal disease, such neck stiffness, rash, and photophobia should be watched for (Haj-Hassan et al, 2011; De Battista and Said, 2018). Other, rarer symptoms are confusion or leg pain in a child with an unexplained acute febrile illness (Haj-Hassan et al, 2011).

Conclusions

Fever in children is common, affecting an estimated 70% of preschool children annually, with 40% seeking medical advice (Hussain et al, 2020; Sakr et al, 2022). Fever is classified as a temperature of 37.5 °C or above (axilla measurement).

Fever is the body's physiological response to an infection and, although disruptive, it is usually self-limiting and is gastrointestinal or respiratory in nature. Health professionals are ideally placed to provide evidence-based advice in contemporary treatments to reassure parents and reduce pressure on healthcare services. Careful history-taking and the traffic light system should be used to exclude underlying disease, especially sepsis, with advice to carers about the management of fever help to reduce ‘fever fear’. Paracetamol remains the antipyretic of choice; however, this may be used in conjunction with ibuprofen, alternating if the child remains distressed before the next dose is due (NICE, 2021).