The World Health Organization (WHO, 2024) states that young person pregnancy is still a concern for all nations. The figures for pregnancy in the under-16s for England and Wales are higher than in other European countries, and in 2021 there were 2181 under-16s who were pregnant. Of these, 59.8% chose to terminate their pregnancy (Public Health England [PHE], 2018; Faculty for Reproductive and Sexual Health [FSRH], 2019a; Office for National Statistics [ONS], 2023).

The physical and emotional toll of pregnancy in young people cannot be underestimated. Globally, mothers aged 10–19 years are at higher risk of experiencing pre-eclampsia and systemic infections (WHO, 2024). Teenagers (19 and below) who have children are at a higher risk of experiencing lower birth weights and preterm deliveries (Diabelková et al, 2023). There are 15 forms of contraception available in the UK, only some of which include the use of hormones. Contraception works by one of the following methods:

The only form of contraception that will protect against both pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is the condom, and this should always be encouraged alongside other methods of contraception (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2022).

Assessment for contraception

The FRSH (2019a) has published advice on how to conduct a consultation with a young person (Table 1).

| Initial contact | Reception staff | As they are often the first point of contact for the young person with the service, reception staff should provide a friendly and non-judgemental welcome |

| Consultation process | Health professionals | Wherever possible, the young person should be allowed as much time in the consultation as they need |

| Time should be taken to explain the confidentiality to be expected from all medical and non-medical staff in the healthcare team and the limits of confidentiality | ||

| Avoid making assumptions about reason for visit, sexual behaviour, sexual orientation, risk or capacity based on age, gender or disability | ||

| Avoid writing notes while listening and observing | ||

| Avoid appearing to moralise about sex, sexuality and contraceptive choices, and be aware of cultural and sexual diversity | ||

| Barriers such as desks and computer screens should be minimised |

When assessing a young person for contraception the following should be discussed as a minimum:

The following should also be considered:

Gillick competency and Fraser guidelines for the under-16s

The terms Gillick competency and Fraser guidelines are used often used interchangeably in healthcare, and are applied in many health contexts when discussing care provision and medical treatment in under-16-year-olds.

Gillick competency assesses young people's ability to understand and assimilate information, their capacity to consent and to make rational decisions about their health and treatment (CKS, 2024a). In Scotland, the Age of Legal Capacity Act (1991) is applied rather than Gillick competency (NSPCC, 2022).

The Fraser guidelines apply to advice and treatment about contraception and sexual health. When considering whether contraception should be supplied to young people under the age of 16, according to the guidelines, there is no legal obligation to advise the young people's parents or guardian of this decision. However, it is good practice to encourage the young person to discuss this with them, or to ask if they will give consent for the health professional to do so. If the parent or guardian refuses to allow the young person to accept treatment, this can still be supplied if the young person is deemed Gillick competent (NSPCC, 2022).

The NSPCC (2022) recommends the following factors should be considered in relation to the application of Gillick competency:

Legal considerations and young person abuse

In the UK, the age at which people can legally consent to sexual activity (the age of consent) is 16, whatever the young person's gender or sexuality (Sexual Offences Act, 2003; CKS, 2024a). Penalties for ignoring this vary depending on the age of the young person and their sexual partner.

Where the sexual partner is in a position of trust (for example, a teacher), the age range extends to include those aged 16–18 years. When a child aged 13 or below is involved in sexual acts, this is viewed as a particularly serious offence as they are not deemed capable of giving consent, and sexual activity is therefore deemed as assault or rape (Sexual Offences Act, 2003; FRSH, 2019a). It is important to determine, whenever possible, that the young person is not being coerced into having sex and/or using contraception against their will. Where young person abuse is suspected, it is the professional duty of the healthcare clinician to undertake a risk assessment and report this to the appropriate local safeguarding team and/or the police (Royal College of Nursing [RCN], 2021).

It can be difficult to determine whether a young person is being sexually abused if they are not forthcoming with information, and health professionals need to be trained to notice cues, such as non-verbal behaviours. Good questioning and listening skills, and frank discussion around confidentiality and safeguarding, are essential so that the young person feels safe and supported. It is also important to give the young person as much time as possible to encourage them to explain their experience (Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2021; RCN, 2021).

As well as the application of local resources and guidelines, many other organisations such as the NSPCC and the RCN provide guidance on safeguarding and young people abuse (RCN, 2021; NSPCC, 2022). The General Medical Council (GMC, 2018a; 2018b) provides good guidelines for doctors on the protection of young people, which is applicable for use by most health professionals.

Contraceptive options for young people

When determining an appropriate form of contraception, eligibility screening should be undertaken using the UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (UKMEC) (FSRH, 2019b) and recognise advice given by the WHO (2015). The UKMEC reviews potential risks for specific contraceptive forms based on issues such as comorbidity (including family history) and rates risk as low to high (FSRH, 2019b). There is also an online calculator available to work out risk at: https://www.ukmec.co.uk (the calculator tool is not affiliated with the FSRH).

When considering the best form of contraceptive to advocate, age should not be the only factor. The use of hormonal methods is not advocated prior to menarche and condoms should be offered as the preferred method (FSRH, 2019a; 2019b). Condoms should also be advocated for use alongside other contraceptive measures to reduce the risk of STIs (NICE, 2022).

Hormonal contraceptives may be the most useful option when treating concurrent common menstrual issues such as acne, pain, heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding and iron deficiency anemia (Healthy Children. Org, 2024). It should be noted that altered bleeding patterns may occur with some hormonal methods and with the copper IUD. There may also be mood changes with the use of hormonal contraceptive methods, but evidence does not indicate that it is a cause of depression (FSRH, 2019a).

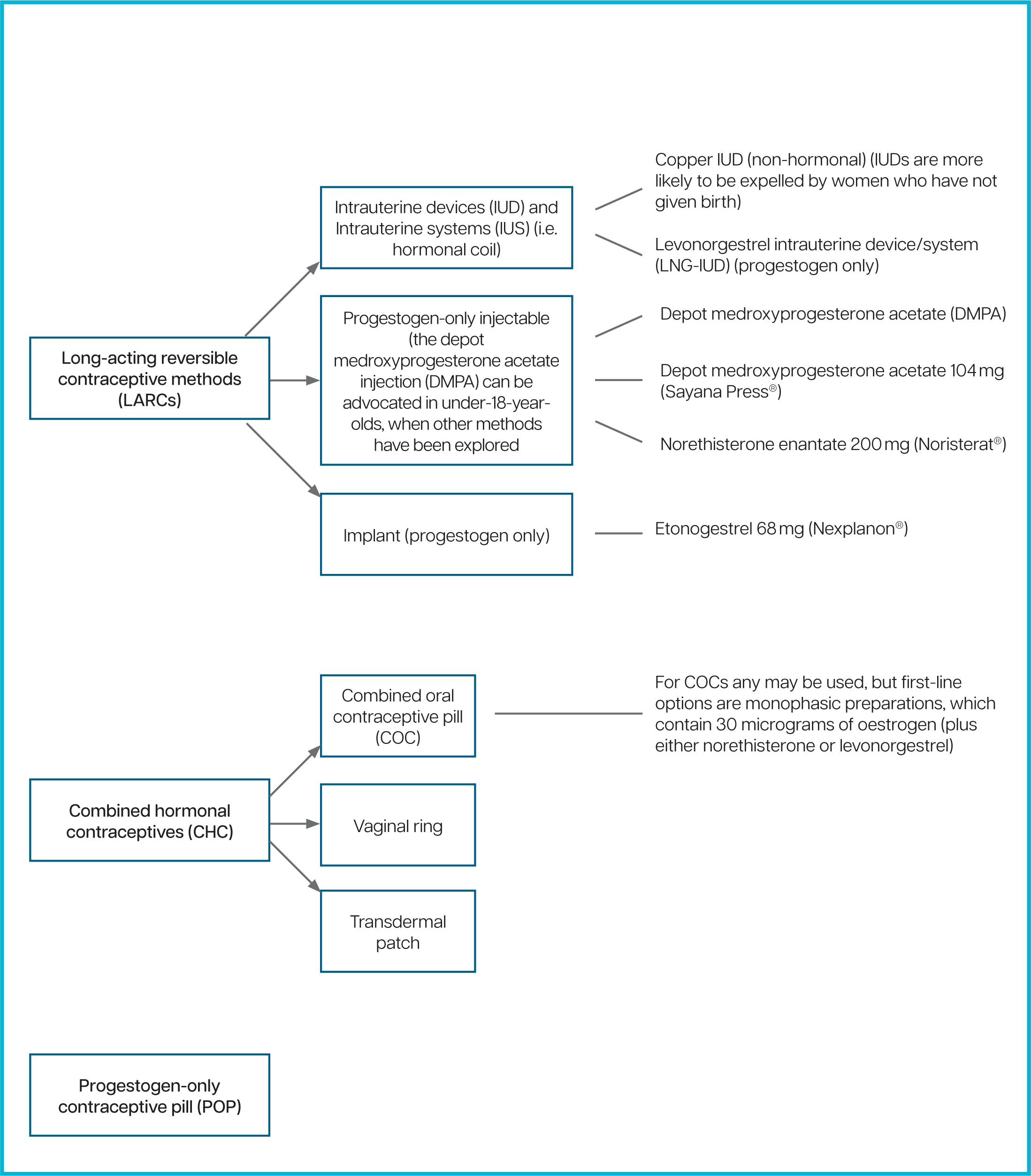

While oral contraception remains the most popular method (NHS Digital, 2021), long-acting reversible contraceptive methods (LARCs) such as intrauterine devices, intrauterine systems (IUS), the transdermal implant and progestogen-only injectable injections, should ideally be promoted first-line.

LARCs are defined as ‘requiring administration less than once per cycle’ (NICE, 2022). They are also the most effective form of contraceptive in terms of reducing pregnancy risk (excluding female sterilisation) and are now advocated for use on nulliparous girls (RCN, 2021).

LARCs can provide long-term contraceptive cover, which helps to maintain concordance, as some young people are less likely to comply with taking daily oral contraceptives (FRSH, 2019a; NHS Digital, 2021; Family Planning Association [FPA], 2022; NICE, 2022).

While the choice of LARCs is low in younger age groups, the transdermal implant has proven popular with younger women, with 35% of under-16s (compared to 12% of those aged 45 and over) using this method (NHS Digital, 2021). It is important to note that IUDs/IUCs and the implant can only be inserted by appropriately trained staff (CKS, 2023a), which may reduce immediate access. Always review the licensing information for selected products for age range use, as some of these may not be licensed for use below 18 years of age.

The most widely used methods of contraception are shown in Figure 1. Other forms of contraception include diaphragm or cap, natural family planning, internal and external condoms, or sterilisation (NHS, 2024a). Table 2 details some of the common risks and benefits of specific contraception types.

| Common risks and side effects associated with contraceptive use | Benefits associated with contraceptive use | |

|---|---|---|

| Weight gain | The use of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) has been associated with some weight gain | There is no evidence of weight gain with combined oral contraceptive (COC) and little evidence with progestogen-only pill (POP) use |

| Acne | The progestogen-only implant may improve this (or make it worse) | The use of COC products can help to reduce acne |

| Irregular bleeding/pain | Intrauterine device (IUDs) and intrauterine system (IUSs) and the implant may cause irregular bleeding |

The levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD), COC and progestogen-only injectable may be useful in treating heavy menstrual bleeding |

| Fertility | Fertility delays of up to 1 year have only been noted with DMPA use | No delays to fertility have been noted with other contraceptive types |

| Bone mineral density | DMPA users may experience a small loss of bone mineral density, which usually returns to normal after stopping use | No loss of bone mineral density in other contraceptive products noted |

| Cancer risk | CHCs have a small increased risk of breast cancer (which reduces when the CHC is stopped) and a small increased risk of cervical cancer with prolonged COC use | The use of COC reduces ovarian cancer risk and this protection continues after the product is stopped (it provides approximately 15 years of additional protection) |

| Venous thromboembolism | There is a small risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) occurring with CHCs |

Little or no increase in the risk of VTE with progestogen-only methods |

Advice on chosen contraceptive method

The following factors should be discussed once the method has been chosen (FSRH, 2019a; NICE, 2022; CKS, 2024a; CKS, 2024b):

Contraception is freely available in the UK from the NHS through GP practices, genitourinary medicine (GUM) and sexual health clinics, family planning clinics and pharmacies – including online (NHS, 2024b). It can also be obtained through private providers, such as Brook clinics (Crossman, 2022). Further support can be accessed using the National Sexual Health Helpline: 0300 123 7123 (NHS, 2024a).

All information provided during the consultation should be supplied in the most appropriate format for the young person; for example, written information and website links. Remember that some young people may not want paper information, which could be found by parents or guardians.

Emergency contraception

There are three free methods of emergency contraception (EC) available in the UK (if young people are not eligible for NHS Scotland services, the emergency contraceptive pill can be bought from most pharmacies), all of which may be offered to young people when there is a risk of unwanted pregnancy. Evidence shows that younger people require more access to ECs than older groups (FPA, 2022). It is important to discuss with the young person that the use of EC is not considered as a form of abortion (CKS, 2023d). ECs can be inserted/taken from 3–5 days following sexual intercourse. The copper IUD is the most effective method of emergency contraception and should ideally be the first-line option, even for individuals presenting at less than 5 days post-sexual intercourse, as it may remain in situ to provide continued contraception cover (FSRH, 2019a).

| Type of contraception | When it can be taken |

|---|---|

| Ulipristal acetate emergency contraception (EC) (UPA-EC) 30 mg single dose tablet | Licensed be taken up to 120 hours (5 days) after unprotected sex |

| Levonorgestrel EC (LNG-EC) 1.5 mg single dose tablet | Licensed be taken up to 72 hours (3 days) after unprotected sex |

| Copper intrauterine device (Cu-IUD) | Licensed to be inserted up to 5 days after unprotected sexual intercourse, or up to 5 days after earliest ovulation date |

Advance prescribing of oral ECs is a debated topic, but evidence does not support the premise that it is more effective in reducing unwanted pregnancy than standard methods of EC access. However, it may be a useful consideration in promoting the use and understanding of the role of EC in preventing pregnancy (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2017).

Consider ‘quick starting’ of other contraceptives at the consultation, provided there are no contraindications and where the young person is not pregnant or at risk of pregnancy (FSRH, 2017).

Barriers to accessing contraception in young people

It has long been recognised that there are still potential barriers to young people accessing contraception and contraceptive advice, which was further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and reduced access to services, coupled with conflicting information (Lewis et al, 2021).

In 2014, the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) highlighted the following barriers:

Conclusions

Contraception provision for young people, especially to those under the age of 16, is complex. While the prevention of unwanted pregnancy is the goal, so too is the identification and protection of the vulnerable. It is vital that staff are educated in safeguarding and referral pathways, and that Gillick competency and Fraser guidelines are effectively applied before supplying contraception to this younger age group.

Services for young people need to be as varied, wide reaching and accessible as possible, with all avenues and opportunities for education and support explored. Young people should be encouraged to actively seek contraception advice, and health professionals must remain objective and professional during contact if they are to assist in reducing the incidence of unwanted teenage pregnancy.